Final Odyssey

His eyesight is faltering, his legs are gone and his breath comes in

gasps, but the nimble mind of Arthur C. Clarke continues to propel this quick-witted

futurist to the farthest reaches of human possibility.

An interview with the living legend.

By Ron Gluckman/Colombo

![]()

T

HE CLATTER OF KEYS PRECEDES THE raspy voice, booming and boisterous even from behind the closed door. "Sit down. Sit down," insists Arthur C. Clarke, godfather of the modern science fiction genre.In the dim light of his suite at the Galle Face Hotel, it’s difficult to see the crusty writer, but I can hear him snickering as his fingers fly at break-neck speed across the laptop keyboard. "Just a moment," he grunts, in that dazed voice of a great writer’s distraction, seemingly from a galaxy away. As the sea laps against the rocks just outside the window, I’m lulled to sleep. Then, I’m startled awake when he shouts: "That’s it! Finished!"

Just like that, the man who expanded not only the horizons for science fiction writing,

but, in many ways, the actual daydreams of the mankind, has completed "3001, The

Final Odyssey."

Just like that, the man who expanded not only the horizons for science fiction writing,

but, in many ways, the actual daydreams of the mankind, has completed "3001, The

Final Odyssey."

Clarke, who has lived in Sri Lanka for four decades now, is clearly on his last legs. He walks unsteadily with the help of a cane, but increasingly depends on a wheelchair. Simply talking for any length of time is a painful chore. Still, that doesn’t stop him from telling some of the dirtiest jokes I’ve heard in years.

And, when I wonder aloud whether this will be his final odyssey book, he quickly snaps: "Gawd, I hope so!" Then he repeats the same dirty joke about a gorilla and some nuns that he told two days ago when we first met.

He talks a mile a minute during a series of short talks - "I don’t give interviews anymore," he grumbled at our first meeting. "I’ve done over 1,000 of them. I’m all done." Then the pain pulls him down again. His mood fluctuates from a kind of frenzied friendliness - like an elderly loner on the porch of an old folk’s home - to a distant dreaminess, as if his consciousness keeps launching into space, leaving his tired body behind. He admits to being especially jittery today.

But it’s not because of the book, although he concedes a certain joy about "sleeping with ‘3001’. That will be nice. I’ll be up at 3 a.m. with some idea. I don’t really work on it," he notes. "But I’ll have ideas. If they’re any good, I’ll remember them in the morning."

Right now, though, he has more interesting matters on his mind. While the world awaits news about the latest installment in the fascinating series that helped define the 1960s - the film of "2001: A Space Odyssey was released in April 1968 - Clarke is consumed with his own personal anxiety. Soon, the first pictures from Ganymeade will come from the space probe, Galileo. The moon of Jupiter is the setting for his Odyssey books.

"I can’t wait," he admits, then explains his expectation. "It will probably look like Greenland, with glaciers and ice. I’m anxious to see if I’m right. Of course, I’m there over 1,000 years from now in the new book."

Not that he should worry about his prognostication skills. Clarke invented the concept of satellites in the 1940s - the Clarke Belt, where they orbit, is named for him. The fax and e-mail are other innovations he described long before reality caught up the explorations of his far-reaching mind.

That mind is still in space, taking bold leaps. "I’d really like to see proof

of extra-terrestrial life in some form or another," he says of his remaining goals.

Yet time may be running out for this space pioneer. His physical deterioration is due to

post-polio syndrome. "Not much is known about it," he says, grimacing with

recurring pain. "That’s because hardly anyone has lived long enough to get

it!"

That mind is still in space, taking bold leaps. "I’d really like to see proof

of extra-terrestrial life in some form or another," he says of his remaining goals.

Yet time may be running out for this space pioneer. His physical deterioration is due to

post-polio syndrome. "Not much is known about it," he says, grimacing with

recurring pain. "That’s because hardly anyone has lived long enough to get

it!"

But in his moments of lucidity, when the pain fades, he exhibits dazzling insightfulness. And the curiosity and excitement of a child. One minute he is talking about the need to develop better propulsion systems to make space travel affordable, and the next, he’s showing off new software that will add voice recognition to his computer system. In between, he shares a fax that just came from Steven Spielberg. The director has taken an option on "Hammer of God," Clarke’s last book, his 80th, he thinks. "I’ve lost count." He also loses interest in discussion of the deal, more intent on showing off the cartoon that Spielberg faxed him.

This is how creativity works, this meteor storm of ideas and the race to take each to the limit. A self-professed "info-maniac" Clarke found a strange home for his science fiction books. He first came to Sri Lanka in 1952, fell in love with the island and returned for good two years later. His house is filled with televisions, video machines and computers, but he’s hidden away here at the Galle Face Hotel to write what may be his final book. And it’s a fitting setting. The 132-year-old grand dame of South Asia’s hotels is in a magnificently advanced state of decay and grandeur. As we sit together, the ocean licking our toes, I thinks it’s a great treat to be with two of the legends of Sri Lanka, watching to see which crumbles first into the sea. But there’s no time for idle daydreams. Clarke is chattering again.

"Hey, did you hear the one about the three nuns who went to see the gorillas at the zoo?"

![]()

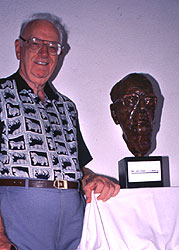

Ron Gluckman spent several weeks visiting with Arthur C. Clarke in Sri Lanka in the summer of 1996, when he was finishing his latest book, "3001, the Final Odyssey." This story appeared in the Wall Street Journal, but other Clarke pieces penned by Ron Gluckman appeared in Serendib and Asia Magazine. For other stories by Ron Gluckman from Sri Lanka, please turn to solar chimney, tourism, Jaffna or President Chandrika Kumaratunga.

![]()

To return to the opening page and index

push here

![]()

[right.htm]