The Lady and the Tramps

Fear and longing prevail inside Burma, where a brutal military junta continues to rule with an iron hand, but cannot subdue the lady who lives, virtually a prisoner, inside the lakeside home of her father, the martyr of a nation that still waits for justice and democracy. The story of a heroine.

By Ron Gluckman/Yangon

B

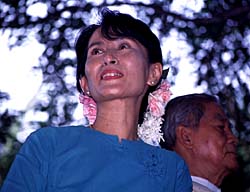

EYOND THE BARRICADES AND barbed wire, in full view of surveillance agents, history continues to unfold in the quiet confines of the compound on University Avenue. Set alongside a lake, and shaded by trees, the sixty-year-old, two-story abode hardly looks newsworthy. Yet, during the present decade, it’s been seen on nearly as many newscasts as the White House or Kremlin.The seemingly innocuous nature of the house is emphasized by the appearance of its sole occupant. She arrives after the guest log has been signed, and permission to enter has been granted by government guards at the gate. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is demure and soft spoken in conversation, but, depending on whether you believe the military rulers of Burma or the Nobel committee, she is either a puppet of imperialism or one of the most courageous women alive.

For much of the

past six years, Burma’s military junta have held "the lady," as she is

known nationwide, in house arrest. For five years, she was allowed no visitors. Even after

her release a year ago last July, her movements have been restricted, her followers

arrested and, often, abused. Her weekly speeches are uniformly condemned by the state

press.

For much of the

past six years, Burma’s military junta have held "the lady," as she is

known nationwide, in house arrest. For five years, she was allowed no visitors. Even after

her release a year ago last July, her movements have been restricted, her followers

arrested and, often, abused. Her weekly speeches are uniformly condemned by the state

press.

To Aung San Suu Kyi, and legions of supporters around the world, all this intimidation proves the strength of the democracy movement in Burma. It’s surely an indication of Suu Kyi’s incredible popularity in Burma, where her father, Bogyake Aung San, is revered as the national hero. The leader of the movement that won independence from the British, he was assassinated in 1947, exactly 42 years and a day before the Suu Kyi’s solitary confinement started. She was two when her father died, but has continued the battle for freedom.

But the fight isn’t over yet, and may not be for a long time. Suu Kyi, who won the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize, seems no closer to power now than in any time since 1989, when she and her National League for Democracy (NLD) won a landslide victory in Burma’s first free election, results that the junta refused to honor.

However, this past summer (1996) has seen a stormy change in the political game of cat and mouse played between Suu Kyi and the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), as the junta that seized power in 1988 is known. In late May, Suu Kyi took the initiative, calling a convention of the NLD. SLORC responded by arresting nearly all of the delegates, but the few who escaped went ahead with the meeting at the University Avenue compound. Crowds grew to the thousands around the compound for Suu Kyi’s regular weekend talks in ensuing weeks, which were filled with rumors of even more arrests and repression.

In June, SLORC banned criticism of its rule, effectively outlawing the NLD and Suu Kyi’s public addresses. Overnight, signs went in the capital of Rangoon, by her house and the United States embassy, denouncing foreign interference in Burmese politics. Suu Kyi, who is married to a British university professor, was attacked as a "western party girl" and "foreign stooge" in the official state media.

Suu Kyi defiantly went ahead with the talks anyway. Nothing happened, not right away. But a few months later, there were more mass arrests, and increased military presence on University Avenue, designed to end Suu Kyi’s dialog with the people. Reporters were barred from her house, and one western embassy worker was briefly detained. Despite all this harassment, Suu Kyi vows to battle on for, she says, "what rightfully belongs to the Burmese people, democracy, and the right to determine their own future for themselves."

Away from the glare of cameras, inside the house where she has spent much of the last decade formulating plans for democracy in Burma, Namaste visited with Aung San Suu Kyi on two separate occasions. In the midst of the political turmoil of Burma’s long hot summer, we talked with the woman Vanity Fair termed "the world’s most famous political prisoner," about the prospects for peace in this troubled land, about the world’s role in the battle and, briefly, about personal matters, including the family she left in England in 1988, when she returned to Burma to care for her sick mother.

Suu Kyi glides into the room, like a cat. Her movements are graceful, elegant. The woman who challenges one of the world’s most repressive military regimes stands only five-foot-four inches. The years of imprisonment resulted in her weight dropping from 106 to 90 pounds. She also developed spondylosis, a degeneration of the spinal column that continues to pain her.

She passed much of her time in house arrest in the garden, which had fields of Madonna

lilies, frangipani and lots of jasmine. "That’s my favorite flower," she

says of jasmine. She rarely appears in public without a bundle pinned behind her ears,

adding to her fragrant appeal.

She passed much of her time in house arrest in the garden, which had fields of Madonna

lilies, frangipani and lots of jasmine. "That’s my favorite flower," she

says of jasmine. She rarely appears in public without a bundle pinned behind her ears,

adding to her fragrant appeal.

Suu Kyi also has fondness for music - "mainly baroque," she says - and reading. She favors novels, and gratefully accepts a copy of the latest by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. She recently finished one by Sommerset Maughan, who reminds her of the home in England where her husband, a Tibetan scholar at Oxford University, lives with their two sons, Alex and Kim. Michael Aris, whom she married in 1972, has visited Burma, but the two boys have passed through their teens without her. "I talk to them on the phone," she says, then quickly changes the subject. Clearly, the years of separation have taken an immense toll, but Suu Kyi doesn’t like to discuss personal details.

Surprisingly little is printed about the past of this courageous woman. She spent much of her youth in Delhi, where she attended a convent school and learned how to play the piano. She still has one in the house. Most of the other furniture was long ago sold to pay for her upkeep while under arrest. She refused, and continues to, any support from SLORC. She reportedly pounded the piano until a string snapped to vent her frustration through the long period of confinement.

She still shows her rage in little ways. She balls her hands into fists as she talks about the political situation in Burma. Seated on a wooden chair, under a huge painting of her father, it’s easy to see the resemblance, as have many in Burma. At her first public appearance, more than half a million Burmese came to hear the new firebrand of freedom. They were attracted by the famous name, then mesmerized by the same captivating manner. She is a riveting speaker.

Privately, though, she speaks softly, slowly. But her petite appearance and gentle manners take nothing away from tremendous conviction. "We don’t have a rigid view of what we want for Burma," she says, responding to criticism that the NLD hasn’t put forward a viable plan for running the country, should SLORC ever step aside.

"I am not interested in trying to predict the future. What we are trying to do is shape the kind of future that we want for our country. And that comes about through endeavor," she says. "We just proceed according to our agenda. We have a lot of work to do. We are a political party that represents the people of Burma. In fact, I can say that we are the only organization in Burma that has received a mandate of the people. So there is a lot that we have to do."

Running a political party under SLORC’s dictates is infuriating. The NLD is not allowed to print or distribute its literature, and all communications bearing her image or detailing her speeches is banned in Burma. "We have to write or type out everything," she says, "because we don’t have a license to print or publish and we do not have a license for a xerox machine." The repression can be deadly. A few months ago, James Nichols, an honorary counsel for several Scandinavian countries, died in prison. His crime: illegal possession of a fax machine allegedly used to send some communiqués of Suu Kyi, his god-daughter.

Such repression only strengthens her resolve for democracy and human rights. "We know what is necessary is some basic guarantees. That’s what we mean by democracy. Whatever kind of government we have will have to be guided by the will of the people. By democracy we mean a system that is guided by the will of the people with institutions that will make it possible for that will to be implemented. These are the basics that are common to all democracies.

"But what shape and form that model will take, that is not up to me to say. It is for the people to decide," Suu Kyi adds. "The NLD has always said that one of the first requirements is a general national convention."

She says discussion is the only path forward. "Burma’s problems will only be resolved through dialog. I have said that many times. That is the only way this stalemate can be resolved.

"But getting to middle ground is not something that just one side can do. Both sides have to do it. Dialog means involvement of both sides." And, while she is always willing to talk to SLORC - an unconditional discussion of all issues - she isn’t above a more confrontational tact, as she showed this past summer. "We’re not just going to sit around and hope that the dialog will come about. While working towards dialog there are a lot of other things to do, beginning with the simple nitty gritty of party organization to communicating with the people, to the mobilization of international opinion. We have never made a secret of the fact that we consider international opinion of importance, because we live in a world where everyone is linked to everybody else."

In recent years, SLORC has liberalized some of the isolationist policies that date from the 1960s, when visitors were issued visas that lasted only 24 hours. A spate of hotel building and infrastructure improvement has marked a push for tourism - Visit Myanmar Year 1996, a much delayed and controversial campaign to bring in tourists and hard currency, launches this month. Meanwhile, investment has surged forward in the 1990s. Western nations led by the US, continue to spurn Burma’s calls for foreign investment, but Asian nations have shown little reluctance. Burma is rich in hard wood, gems and oil.

Asian nations advocate a policy of "constructive engagement," which seeks to bring democratic reform to Burma via increased economic development. It’s a policy that has long divided western nations, and after the recent round of arrests in Burma, provoked a reassessment by many members of ASEAN, a body which Burma’s leaders desperately want to join.

Suu Kyi is harshly critical of engagement with SLORC, saying that investment merely props up the repressive regime and postpones the dawn of democracy in Burma. "It has become increasingly clear that Burma under SLORC is not a place where sustained economic development can take place, and it’s not a place that guarantees security for business enterprises." As to restrictions on investment in Burma, which have been adopted by many US cities and are under consideration by congress, Suu Kyi says: "We would support any movement that makes it clear that Burma cannot benefit from a system that represses its people."

Thus far, she says, economic development in Burma has largely benefited SLORC, rather

than the common people, who are drafted by the military and forced to work as slave

laborers on the various projects of the government.

Thus far, she says, economic development in Burma has largely benefited SLORC, rather

than the common people, who are drafted by the military and forced to work as slave

laborers on the various projects of the government.

"I don’t think ASEAN can be an asset to the people of Burma as it is because the people of Burma aren’t in a position to benefit from any engagement between the government of Burma and other countries.

"I have said consistently that Burma as it is, is going to be no asset to ASEAN. Burma is not stable. Obviously, if it were a stable country, it would have no need for SLORC to make all the fuss it did over (the NLD). I am one of those who endorses the view that lack of stability anywhere is a threat to stability everywhere."

Likewise, she believes that support for Visit Myanmar Year 1996 will only hurt the Burmese people and the battle for freedom. "Tourism has it’s good and bad sides, that I hardly need to say. But Visit Myanmar Year 1996 we do not support, because this is just a big SLORC propaganda campaign," she says. "We would not encourage anyone to encourage Visit Myanmar Year 1996."

Finally, she vows to continue the fight for freedom until it is won. "We will continue with our efforts to bring democracy to Burma under all circumstances. Don’t forget that the ANC was declared an illegal organization years ago. Look how long the effort took in South Africa." As to the dangers ahead, she says: "SLORC has been threatening to annihilate us for months. This is nothing new... We will go on. We believe in hoping for the best and preparing for the worst."

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has spent a great deal of time in Burma, or Myanmar, during the 1990s. This story includes comments from a series of personal interviews conducted with Aung San Suu Kyi, in her house in Rangoon, during the tense days after the junta arrested most of her party faithful in late May 1995. Suu Kyi later denounced this reporter and Asiaweek, which published a lengthy story that Suu Kyi said falsely portrayed the people of Burma as "being more interested in fun and fortune than freedom." For the exact text of the offending story, please click on Down and Up in Myanmar, which appeared in Asiaweek Magazine in June 1996. For other stories by Ron Gluckman on Burma, please click Tracking Myanmar, Rock 'n' Rangoon, or Why Visit Myanmar?

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]