Beijing: Bold? Brazen?

At least architecturally speaking, since a number of new designs are unlike anything ever seen in China, or anywhere else for that matter. Suddenly the focus of many of the world's great architects, Beijing in the run up to the Olympics, is like a blank canvas. Some wonder, though, if all the lavish new strokes are too expensive, and eccentric.

By Ron Gluckman /Beijing

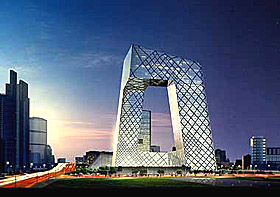

"THIS IS OUT FIRST HIGH-RISE. We wanted to do something different than your typical, two-dimensional, obvious skyscraper," says Ole Scheeren, director of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), the cool Dutch design firm founded by Rem Koolhaas.

OMA's new project is sure to make a big splash in Beijing, a city still characterized by conservative, Stalinist architecture. Koolhaas, who previously proclaimed the skyscraper to be dead, certainly intends to give life to a decidedly atypical high rise. In fact, simply describing it is pretty nigh impossible, Scheereen concedes.

The new headquarters for CCTV, China's state

television network, will most resemble a cartoon version of the letter

"Z." At 230 meters high, the brightly colored, continuous loop with

no right angles will tower over every other building in

the city upon completion by 2008.

The new headquarters for CCTV, China's state

television network, will most resemble a cartoon version of the letter

"Z." At 230 meters high, the brightly colored, continuous loop with

no right angles will tower over every other building in

the city upon completion by 2008.

Next door, a companion structure will take on the shape of a trapezoidal boot. These will provide more than 550,000 square meters for CCTV studios, offices, exhibitions and a hotel. Each of the unconventional structures would stand out in any city, at least upon this planet.

Yet, across Beijing, the once-stodgy urban landscape is sprouting a number of other avant-garde structures, all designed to prove the communist capital isn't so much old fashioned, as innovative, artistic, with-it.

Nor is this merely a Beijing phenomena. From Chongqing to Xiamen, Chinese cities are falling over themselves in the race for flash architecture, the perceived badge of hip. Shanghai has its shelter-skelter skyline, and Shenzhen sports a Viva-Las-Vegas look. Beijing, however, had always been content to be square.

Not anymore. In fact, even Cold War throwbacks like Tiananmen Square no longer offer respite. Behind the Great Hall of the People, a site the size of four soccer pitches incubates a structure that some call the "Alien Egg."

In a daring design by French architect Paul Andreu, the three halls that comprise the new National Theater are tucked inside an egg of titanium and glass. When it opens within the year, this striking egg will float upon an artificial lake, currently at the moat stage. Visitors will enter by escalator and appear to plunge into the water--with Mao's portrait at the Forbidden City behind them.

Unsurprisingly, this radical design provoked so much public outcry that it was repeatedly halted for reconsideration. Critics complained that it was too expensive, modern and foreign, especially considering its location at the very heart of the People's Republic of China.

Architects and engineers circulated petitions to kill the project. In the end, it was scaled back from a $500 million design with four theaters to the $300 million three-theater egg that now, fully framed on Beijing's main boulevard, looks like something hatched from a galaxy far, far away.

Yet, such quabbling may be a thing of the past. Just three years after all the controversy over Mr. Andreu's "Alien Egg," the CCTV tower -- dubbed by locals as the "Twisted Donut" -- has hardly raised a peep of protest, even as costs soared to $700 million. Mr. Scheeren confides that there have been questions, mainly over the engineering realities of this truly radical design.

Understandable, since many of the construction processes have never been attempted. OMA mainly had to demonstrate the logic of its structural design. Full approval was given in January, and Beijing authorities didn't even blink at the new cost estimate, even though its several times that of any previous OMA project.

In the short space of a few years, Beijing's entire shell of conservatism seems to have shattered. "The mind here has changed quite radically in recent years," says Mr. Scheeren. "In America and Europe, there is very little readiness to do things of this scale and impact right now. A project like this would be impossible to do anywhere else in the world."

Has Beijing's taste matured? More likely, the capital desperately desires to update its dowdy image before it hosts the 2008 Olympics. Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, who designed London's Tate gallery, are signed for a $460 million skeletal steel Olympic Stadium that resembles a bird's nest.

Lord Norman Foster was given the nod last November for a $1.9 billion airport expansion, and drawings show a futuristic runway flanked by an ice-block-like terminal.

And there are many more of these building to come. The Twisted Donut and 170-meter boot are the first of 300 towers to rise in a new central business district. In the suburbs are sites for science parks and other theme developments, as well as luxurious subdivisions with names like Margarita Island, Glory Vogue, Latte Town, Palm Springs and Yosemite Village.

Local architects have mixed feelings about these new, western-flavored designs. While most welcome fresh ideas, few can't help but envy the stratospheric sums earned by these famous -- and foreign -- architects. Some also question if these building are appropriate for Beijing.

"Most Chinese don't have problems with foreign architects. They are eager to learn, exchange ideas," says a prominent Beijing architect, who requested anonymity. "But some of these ideas are bad." He singles out both the National Theater and the CCTV building as over-arching, misplaced and ridiculously expensive. "Nobody wants to see Beijing being played the fool."

Lin Gu, a local reporter, recently returned to Beijing after a year of study in Europe. "This city is increasingly unrecognizable, and it feels alien, all this avant-garde architecture," he says. "Many people in Beijing have been brainwashed to think big buildings - however ugly - are modern."

Average Beijingers, meanwhile, have little idea what is coming to their skyline

soon, or the cost, but are proud of anything that seems to improve the standing

of the capital. "All these big buildings make Beijing seem like a city of

the world," says a proud cab driver, who quickly asks: "Is this what

New York looks like?"

Average Beijingers, meanwhile, have little idea what is coming to their skyline

soon, or the cost, but are proud of anything that seems to improve the standing

of the capital. "All these big buildings make Beijing seem like a city of

the world," says a proud cab driver, who quickly asks: "Is this what

New York looks like?"

Others grieve the demise of the tiled-roof homes and alleys that gave the city its ancient charm. The Chinese-born architect, I.M. Pei, on a visit a few years back, bemoaned the quest to build ever higher. "I said long ago, you should be able to look out over the walls of the Forbidden City and see nothing but blue sky. Of course, now it's gray sky," he added bitterly, "but you see sky."

For how long, though? Few Beijingers are questioning the Twisted Donut, or the erection of 300 new towers in a formally low-lying city that had long resisted the instant skylines embraced by the rest of the country. This may mean that the time is finally ripe for Beijing to take on the appearance of a bright, bold world capital.

Still, some local architects can't help but worry that the current urban free-for-all will leave Beijing with egg on its face.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter, formerly based in Beijing (2000-2004), who has written about architecture in China for many publications. This piece appeared in the Asian Wall Street Journal in April 2004.

For another story on Architecture in China, see architecture at a junction

Photo of Andreu's National Theatre (now open, in 2008) by Ron Gluckman. All others are artist renditions from the architectural firms.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]