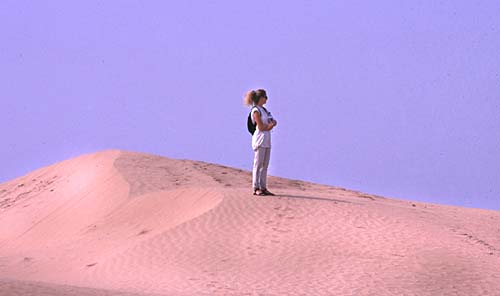

Beijing's Desert Storm

The desert is sweeping into China's valleys, choking rivers and consuming precious farm land. Beijing has responded with massive tree-planting campaigns, but the Great Green Walls may not be able to buffer the sand, which could cover the capital in a few years

By Ron Gluckman /Beijing, Fengning and Langtougou, China

FROM HIS ROOFTOP, Su Rongxi maintains an unsteady balance, perched between the past and a precarious future. One foot is planted firmly upon his tiled roof. The other sinks ankle-deep into a huge sand dune that threatens to engulf his house and Langtougou village, where his ancestors have lived for generations. For this dirt-poor town in Hebei province, the sands of time aren't just a quaint notion, they are close at hand, burning the eyes and lungs. And for Langtougou, the sands seem to be ticking out.

"We have no money to move and, besides, who would have us?" says

Su. "There's nothing to do but dig away the sand and wait to see what

happens. Sometimes I dream of the sand falling around me faster than I can dig

away. The sand chokes me. I worry that in real life, the sand will win."

"We have no money to move and, besides, who would have us?" says

Su. "There's nothing to do but dig away the sand and wait to see what

happens. Sometimes I dream of the sand falling around me faster than I can dig

away. The sand chokes me. I worry that in real life, the sand will win."

Su and his neighbors are ethnic Manchurians who survive by cultivating

subsistence crops and raising horses, goats and pigs. But this year violent

sandstorms dumped entire dunes into the once-fertile Fengning county valley. Now

most of the grass is gone and the Chaobai River stands dry. Besieged villagers

say they have no idea where the sand came from. The scary bit? Su's

almost-buried house is nowhere near the heart of China's rapidly encroaching

deserts. It is just 160 km north of Beijing. Suddenly, rural Langtougou has

become a barren outpost on the front line of a national battlefield.

Premier Zhu Rongji raised the war cry in this very village in May, after the

worst sandstorms in memory buffeted Beijing. Zhu stood on Su's roof, pledging

urgent measures to combat the encroaching sand. Then the premier left with his

entourage, a huge government caravan, on 1,000-kilometer safari across China's

desert hotspots. The next month newspapers ran daily stories about

desertification as armies of tree-planters were mobilized. The 5th Plenum of the

Communist Party Central Committee, starting Oct. 9, has put the issue near the

top of its agenda. Zhu has called it "an alarm for the entire nation."

Su, 53, missed that address — and the visiting premier. Su was in the

grass-stripped hills tending his hungry goats. He doesn't know much about the

goings-on in Beijing anyway, having never traveled further than Fengning's

county seat, about 25 kilometers away. That trip used to take 40 minutes; now it

can last days. Local workers cleared a path for the premier, yet just weeks

later the road vanished — reclaimed by the relentless desert.

Few people think of China as a desert nation, yet it is among the world's

largest. More than 27%, or 2.5 million square kilometers, of the country

comprises useless sand (just 7% of Chinese land feeds about a quarter of the

world's population). A Ministry of Science and Technology task force says

desertification costs China about $2-3 billion annually, while 800 km of railway

and thousands of kilometers of roads are blocked by sedimentation. An estimated

110 million people suffer firsthand from the impacts of desertification and, by

official reports, another 2,500 sq km turns to desert each year.

This is nothing new, of course. In the 4th century B.C. Chinese philosopher

Mencius (Mengzi) wrote about desertification and its human causes, including

tree-cutting and overgrazing. Experts argue over the reasons and consequences,

but all agree that Chinese deserts are on the move. Sand from the distant Gobi

threatens even Beijing, which some scientists say could be silted over within a

few years. Dunes forming just 70 km from the capital may be drifting south at

20-25 km a year. Conservative estimates say 3 km a year. And despite massive

spending on land reclamation and replanting, China is falling behind.

In the

northwest, where the biggest problems lie, desertification has escalated from

1,560 sq km annually in the 1970s to 2,100-2,400 sq km in the 1990s. According

to many environmentalists, Beijing has been largely content to issue

proclamations about student-supported tree-planting rather than tackle

complicated land issues.

But that was before clouds of grit roared through the capital this spring.

Sandstorms are hardly novel in Beijing, but the sheer ferocity of these tempests

was. For days on end, wave after fearsome wave, sand closed the airport and

casualties filled hospitals. Just as surprising was the public outrage. Even

state-run media lambasted government officials. The frustration is easy to

understand. According to Chinese records, dust storms came to the capital once

every seven or eight years in the 1950s, and only every two or three years in

the 1970s. But by the early 1990s, they were an annual problem.

The government

responded with huge "greening" campaigns and in the past 20 years

alone, according to the People's Daily, more than 30 billion trees have been

planted. This year, however, the storms blew away any sense of security.

Grasping the enormity of the problem is easy on the road north from Beijing to

Langtougou. Nestling among fields of corn and sunflowers, villages bloom with

flowers. After two hours' driving, the views are still green. But over one steep

mountain a surreal landscape astounds the eyes. Mountains rise on both sides of

the valley ahead, but the hills are an ugly gray, denuded of vegetation. Even

weirder, hillsides are dotted with white, much like highway stripes stretching

into the horizon.

Grasping the enormity of the problem is easy on the road north from Beijing to

Langtougou. Nestling among fields of corn and sunflowers, villages bloom with

flowers. After two hours' driving, the views are still green. But over one steep

mountain a surreal landscape astounds the eyes. Mountains rise on both sides of

the valley ahead, but the hills are an ugly gray, denuded of vegetation. Even

weirder, hillsides are dotted with white, much like highway stripes stretching

into the horizon.

The real shock hits on the descent into the valley. Those dots

are actually white-painted stones, lining small pockets of soil. Inside each is

a tiny tree. But the entire countryside has been stripped of grasses, topsoil

and mature trees — meaning the saplings have little chance of survival.

In Langtougou, residents are mumbling about new regulations as they dig huge

pits in their yards to compost manure and waste to produce fuel. Each house must

have one as part of a government decree against burning wood. Firewood

collection (32.4%) is a key cause of desertification in northern China,

according to a study by Chinese researcher Ning Datong and published by the

University of Toronto. Ning attributed the other causes to excessive grazing

(30%) and over-cultivation (23.3%).

None of the 200 villagers is enthusiastic

about their new composting brief, but what really upsets them are the other

initiatives. Farming will cease, and they have also been told they will have to

give up their animals. "This is how we live," says Li Guoyun, 50.

"We have 50 to 60 goats. We sell the wool and some for food. Without them,

we'll be ruined." Li realizes, of course, that his goats gobble up the

grass that used to cover the valley floor and hillsides, "but they are so

much easier than pigs or cows."

Up and down the silted-in valley, the story is much the same. "I grow corn,

rice, beans and tomatoes, to eat and to sell," says Zhang Baoguan, 43, a

father of two from the nearby hamlet of Caonianguo. "Now, I'll have to

stop. The government is promising some rice and money, but it's not

enough." The moratorium on farming and grazing will apply throughout the

valley — and nobody knows for how long.

Villagers have already been drafted into China's new green army of tree-planters. "We'll plant trees every day for five years," Zhang says dejectedly. "And if that doesn't work, we'll plant for five more. That's what they tell us."

Neighbor Lin Renrui

fears that no amount of tree-planting will bring the valley back to life, since

the government has no plans for the sand. "We don't like this plan at all

— especially the part about the animals," Lin says. "The government

told us we will have to sell them all." And the sand? "That's the real

problem," he says, "not the goats. We ask about the sand. Nobody gives

us an answer."

Environmentalists in the capital, most of whom speak on the condition of

anonymity, say Beijing is missing the big picture. Land and water use,

grasslands and forests, desert and climate changes are all interconnected.

"The response has really been fragmented," says one. Yet now that the

government seems to be throwing its weight behind the issue, some critics call

it overkill. "All of a sudden all you read about is desertification,"

says one foreign observer. "You have to wonder if it's not all propaganda,

designed perhaps to win overseas funding for environmental campaigns."

But

what about all that sand, sweeping down from the Gobi Desert and threatening to

swallow Beijing within a few years. "Silly," responds one official in

the Ministry of Agriculture's ecology section. "There are real problems,

but everything with desertification is exaggerated." He worries that the

current focus misses the step-by-step approaches needed in a well-rounded

environmental package. These include planting grasses first to stabilize and

enrich soil, then trees. "But everything is going fast now and there is no

masterplan."

If ever there is a place to grasp the climatic and environmental changes in

China, it is not out on the vast plains, where herdsmen and farmers battle over

dwindling water resources and tillable land. Instead, it is along an odd stretch

of towering sand dunes just 70 km northwest of the capital. In olden times, this

area was a favorite hunting ground of the imperial family, with forests and

lakes for picnics.

If ever there is a place to grasp the climatic and environmental changes in

China, it is not out on the vast plains, where herdsmen and farmers battle over

dwindling water resources and tillable land. Instead, it is along an odd stretch

of towering sand dunes just 70 km northwest of the capital. In olden times, this

area was a favorite hunting ground of the imperial family, with forests and

lakes for picnics.

Now the woods are gone. Nearby sits the junction town of

Huailai — except that no one calls it that anymore. Even on the road signs it

is Shacheng — Sand City.

The changes also are stark in small villages such as Chai Yuan (Firewood

Garden), about 25 km further northwest. From there it is just a few more

kilometers to Flying Camel Desert, so named because some Chinese entrepreneurs

have surrounded the sand with a fence and charge admission to tourists wishing

to experience the desert. Not that it is much of a desert experience. There are

dune buggies and motor bikes for careering over the dunes, a mock Mongolian

yurt, and camels and Mongolian horses.

Still, there is more at the Flying Camel than exists over the dunes, where huge

waves of sand crash to a halt above Longbaoshan. The village of 800 people was

set up in 1989 to house mountain folk — moved from nearby hills as part of a

resettlement program. The new brick buildings seem impressive, but the village

lacks life. "Nobody has any work," explains Zhang Wengui, 78. "We

grow crops, some fruit and vegetables, that's about all."

At least, that was about all. When farming was banned by Premier Zhu, officials

swept in with their own version of Desert Storm. They introduced a

desertification rehabilitation program, which, thus far, has consisted largely

of fencing in the nearby sand and erecting signs proclaiming: "Controlling

the Desert, State Focus Point." The farming prohibition was mostly a waste

of time as well. Crops wilted long ago.

"We have no water," says Zhang. The two village wells, dug deeper each year, have run dry. The people will likely need to be moved again. In the meantime, no prizes for guessing what they have been doing: planting trees.

"It's part of a big campaign,"

says one villager, who recalls how the local Bank of China staffers joined in

one day. They had no choice. "The officials just went in and told

everybody: 'You have to plant trees today.'"

"It's part of a big campaign,"

says one villager, who recalls how the local Bank of China staffers joined in

one day. They had no choice. "The officials just went in and told

everybody: 'You have to plant trees today.'"

It is a similar picture in thousands of villages across China, where population

growth has meant rampant farming and wasteful irrigation. Yet if mass

tree-plantings register far below the raging-success mark in Beijing's piecemeal

fight to stave off the sands, they still look pretty good next to the efforts at

Flying Camel Desert.

While Longbaoshan villagers go thirsty, workers at the desert park are busy hosing down a dune so tourists can take a toboggan ride.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who is based in Hong Kong and Beijing, but who roams around Asia for a number of different publications including Asiaweek, which ran this Inside Story in October 2000.

Top two pictures courtesy of Ricky Wong, a Hong Kong photographer based in Beijing. Bottom two photos by Ron Gluckman.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]