Haier - China's first global brand

Haier is already China's biggest brand, with thousands of products - everything from smart TVs to washing machines that clean clothes - AND sweet potatos. Yet CEO Zhang Ruimin doesn't want to settle for simply turning this formerly bankrupt Qingdao factory into one of China's biggest companies. He wants to conquer the entire world.

By Ron Gluckman/Qingdao, China

GETTING A HANDLE ON HAIER, China's biggest brand, isn't easy. It makes more freezers, refrigerators and washing machines than any other company - but it also churns out thousands of other products from cellphones to robots, defying the standard wisdom about focus. The group maintains a murky corporate structure built on large state-owned stakes, but management experts from Harvard Business School to Kobe University extol Haier as a model for private-sector companies.

Haier’s iconic chairman, Zhang Ruimin, is just as difficult to

categorize. He rarely talks to the press, but he's certainly

not shy, or lacking in substantial opinions. In person he’s passionate

about his management beliefs, an amalgam of advice from business gurus and

whiz-kid economists.

Haier’s iconic chairman, Zhang Ruimin, is just as difficult to

categorize. He rarely talks to the press, but he's certainly

not shy, or lacking in substantial opinions. In person he’s passionate

about his management beliefs, an amalgam of advice from business gurus and

whiz-kid economists.

From the beginning his trusted top lieutenant executing his strategy has been a woman, Yang Mianmian. But he’s also more old school than many executives running companies in China today.

He quotes ancient Chinese philosophers Lao-tzu and Sun Tzu as readily as management legend Peter Drucker and former General Electric chief executive Jack Welch, whom he calls a personal hero. When Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao visited Haier’s headquarters in Qingdao three years ago Zhang offered homey local hospitality along with Zen Buddhist philosophy.

Somehow it’s all working these days. Haier took over as the world’s top home appliance brand in 2009 and widened its advantage last year, when the Haier name captured 7.8% of the global retail market for white goods, according to Euro-monitor.

After a period of steady but not spectacular growth Haier’s revenue began soaring as it ramped up sales overseas, started seeing big dividends from research and development, and expanded its distribution network to rural China, where Beijing has subsidized appliance purchases since 2007. Acquisitions such as Haier’s deal for parts of Japan’s Sanyo last July are also goosing sales.

Revenue at Shanghai-listed Qingdao Haier jumped 19% last year to $11.3 billion, and profits soared 26% to $416 million. Last September the company, which produces refrigerators and air conditioners, debuted on FORBES ASIA’s annual list of the 50 best big companies in the region. And with this issue it earns a spot on The Global 2000 for the first time. This year analysts expect its revenue to rise another 15% and profits 19%. Its subsidiary, Hong Kong-traded Haier Electronics, which makes washing machines, also is enjoying a banner year: Consensus estimates put its revenue at $9.3 billion this year, up 22% on last year, and profits at $291 million, up 34%.

Reaching the top has been Zhang’s goal since the famous day in 1984, when having just taken over the state-owned Qingdao Refrigerator Co., he cursed the terrible workmanship, lined up 76 faulty refrigerators and gave each of his 800 workers a sledgehammer to demolish the fridges on the spot. Yang joined the factory the same year, and she has served as president since 2000, carrying out much of the international expansion.

Haier has long been credited with building one of China’s only global brands; computer maker Lenovo is perhaps the only other one. As Chinese rivals focused on making goods for foreign brands, Zhang spent heavily to push Haier’s own brands into international markets. He spent $40 million on a plant in South Carolina that opened in 2000, invading the U.S. backyard of competitors such as Whirlpool and GE.

At the same time he’s kept Haier in the forefront at home, where the

group has moved far beyond its mainstay of refrigerators, air conditioners and

washing machines. It geared up slowly in industrial robots, selling only 2,600

over ten years, then suddenly 680 last year. A conventional business strategy

would focus on core products, but Haier serves every niche imaginable, from 3-D

televisions and computers to combination washers that clean both clothes and

sweet potatoes.

At the same time he’s kept Haier in the forefront at home, where the

group has moved far beyond its mainstay of refrigerators, air conditioners and

washing machines. It geared up slowly in industrial robots, selling only 2,600

over ten years, then suddenly 680 last year. A conventional business strategy

would focus on core products, but Haier serves every niche imaginable, from 3-D

televisions and computers to combination washers that clean both clothes and

sweet potatoes.

Some critics say that rather than a nimble new model of competitiveness, Haier is really just a retooled state enterprise, muscling into global markets by, they suspect, drawing on government financing for expansion.

Indeed, largely through the Haier Group that goes back to the state-owned factory - government entities own 46.5% of Qingdao Haier and 57% of Haier Electronics. Haier’s public relations firm in Beijing, Hill & Knowlton, denies this, saying the group is a “collectively owned enterprise,” not government-owned.

But despite the companies’ size, few stock analysts follow the two Haier offshoots, concluding that they’re still too much like state enterprises rather than accountable corporations. And the group won’t comment on Zhang’s compensation or whether he owns any shares; none is listed on public databases. (Yang owns $8.1 million of Qingdao Haier stock.)

Still, legions of admirers hail Zhang as a visionary; he’s a national hero to countless Chinese bloggers, while Haier is among Chinese firms most studied by business consultants.

Tarun Khanna, director of Harvard’s South Asia Initiative, says the group hasn’t necessarily contradicted conventional wisdom because large product lines can offer advantages in emerging markets by raising a brand’s profile and increasing the chances of establishing a foothold in a market. He praises Haier’s commitment to research and customer service. “The thing about Haier is how unique it is in allowing and encouraging a lot of experimentation,” he says. “And I’m struck by how persistent Haier has been in” achieving its goals.

Zhang, 63, might seem an unlikely management guru. Unlike many other top executives in the People's Republic of China, he never studied abroad, nor does he surround himself with newly minted M.B.A.s. He acquired his philosophy largely on his own, through reading and relentless self-improvement. “I have never considered myself an outstanding leader, but I think I’m a person who has indomitable will,” says the once aspiring writer in an article of his. “Once I set a definite goal, I must succeed.”

The son of poor factory workers in Laizhou, north of Qingdao, Zhang never had a chance at a proper education. “Like many at that time, I was unable to complete my schooling,” he says. “During the Cultural Revolution the schools were all closed.”

Instead, he joined the Red Guards and made a pilgrimage to Mao’s birthplace. At 19 he started work at a state-run construction company in Qingdao, a coastal city best known for the German colony that flourished there a century ago and the beer it brewed, Tsingtao. During off hours he would hop on his bicycle and pedal to whatever business and self-improvement seminars he could find.

He rose from the factory floor to leadership roles in the party committee in charge of the factory. In 1984 he was dispatched to run the refrigerator factory, becoming the fourth boss in a year and fully expecting to be the fourth to fail. “The moment I got my order I called my wife and told her to prepare for the worst,” he says. But China was beginning to open up, and Zhang, a voracious reader of business books translated into Chinese, saw potential.

He went to West Germany, where he began a partnership with Liebherr, a leading name in high-end refrigeration units. Besides equipment and technology, the German company provided inspiration. (It also provided Haier’s name. It comes from the Chinese pronunciation of the second part of Liebherr; the “Hai” part in Chinese is “sea,” referring to Qingdao’s seaside location. Early promotions for Haier featured two children, one Chinese and the other blond. There are statues of the children at the headquarters, although the group no longer highlights the formative German partnership.)

China was then renowned for filling quotas rather than needs. “I already knew that I wanted to do something very important, to make a good product,” says Zhang. “In Germany there was zero tolerance. If one thing, even the smallest thing, was wrong, they wouldn’t accept it.”

The game changer was spotting a manhole cover. “Even that had a number! Everything had clear criteria. In China we had nothing like that.”

Zhang remains a zealot about quality control and customer service. Unlike many magnates his age he embraces the Internet and other new technology. “Our philosophy: We always think we are wrong,” he says, as he pours tea, hosting lunch at his headquarters. “We only take the customer’s need as right.”

Then he talks excitedly about new,

interconnected products that provide faster feedback from customers.

Zhang gambled by taking Haier public in 1993 to build two adjacent industrial parks for Haier, eventually spending more than $400 million on construction--an astonishing sum considering that profits in 1992 were less than $9 million.

Today the dozens of buildings form a small city, with ten bus lines, banks, sports facilities, dormitories and a medical clinic.

A showroom displays new products, many not yet released. Haier plows 3% to 5% of its revenue into research and development, boasting ten R&D centers, in China, Japan, Germany and the U.S. That investment is comparable to Western competitors’ and is far more than almost any Chinese counterpart.

“There’s a lot of crazy stuff,” says Harvard’s Khanna of the showroom. “It’s easy for some people to ridicule, but you have to marvel at how they are trying to do things differently. That would be admirable anywhere but certainly more so in Communist China.” Says Zhang: “There have been lots of products that have failed, but we don’t need to talk about that.”

On display are gear such as computer tablets (dubbed the HaiPad) and wall-size televisions with onscreen controls and icons that suggest Haier plans its own applications store. One TV has a 65-inch touch-screen that you can write on; it sells for $12,650 in China.

At the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas in January Haier created a stir with novel 3-D TVs (no glasses required) and a kind of remote control fitted into headgear that’s supposed to allow viewers to control the TV with brain waves.

Haier is bullish on intelligent home devices, such as sinks topped with mirrors that use facial recognition to set the faucet temperature. Heating and cooling systems in bedrooms can sense when a child is in the room and whether they are playing or in bed. Home cabinet-size wine coolers--of which Haier is the world’s biggest seller--advise when a vintage in stock is running low.

Haier claims nearly 10,000 patents and thousands of inventions, with customization extending across its product lines in ways no competitor could afford or care about. But if you were a poor farmer beset by rats, then you’d herald Haier’s rat-resistant refrigerators.

Haier freezers, which stay frosty without electricity for 100 hours, are miracle sellers in Africa and other places with undependable power. And it’s a tribute to Zhang’s mantra about how the customer should dictate the business that in Pakistan Haier added a special sari-gown setting to its washers. “We do have a lot of products,” concedes Zhang. “If you try and study them one by one, it’s difficult to keep track. But we’re looking at service for every customer.”

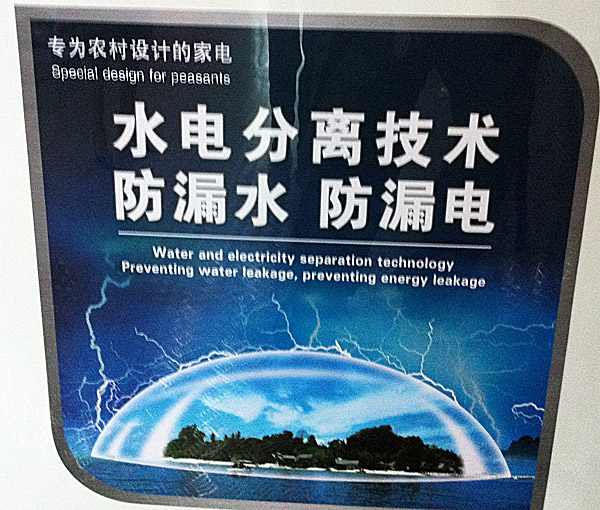

The clothes and sweet potato washer sometimes get derided in the media,

but Haier has sold a half-million of them. It’s on display in the showroom,

alongside another washing machine with a sign that says, “Special design for

peasants.”

The clothes and sweet potato washer sometimes get derided in the media,

but Haier has sold a half-million of them. It’s on display in the showroom,

alongside another washing machine with a sign that says, “Special design for

peasants.”

Zhang is also unorthodox when it comes to overseeing his 80,000 employees worldwide. He’s given to sweeping reorganizations, and under his latest, called “Integrating Order With Personnel,” most employees in China are divided into teams that independently set goals, measure performance and determine bonuses. “Drucker said he wanted everyone to be their own CEO,” explains Zhang. “That’s what we want. We aren’t there yet, but that’s the goal.”

To critics, the campaigns and the slogans are reminiscent of the Communist Party that sent the former Red Guard to the fridge factory. Until last August employees had to wear uniforms; the change followed an online poll of staff, a supervisor says, noting that many still prefer the uniforms. Haier’s teams resemble old-style work units, with meetings that not only decide on targets but also dole out praise and criticism.

Still, there is an undeniable optimism among Haier’s employees. “We are all committed to innovation based on change,” says Li Pan, who joined Haier from university 16 years ago. He’s spent three years as head of American sales and marketing.

Zhang will be 64 in January, yet retirement isn’t likely soon. Talk of holidays also leaves him perplexed; there haven’t been any for years. He says he likes to spend weekends at home reading. His book selection, unsurprisingly, is all thick business manuals. And on Sundays he opens his home for management discussions with Haier staff. “We never miss that,” says Li.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has been living in and covering Asia since 1991, writing for publications around the globe. This piece was published as a cover story in Forbes Magazine in May 2012

Words and all pictures, copyright Ron Gluckman

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]