THE OTHER SIDE OF PARADISE

Defectors from North Korea were once hailed as heroes by brethren in the South. But as more and more arrive, the greeting grows less cheerful and disillusioned defectors wonder why they ever left the People's Paradise

By Ron Gluckman/Seoul, South Korea

![]()

N

OTHING TURNS PEOPLE OFF quite like the tattoo on Paik Ho Chul's arm. In fact, he is so self-conscious about it that he covers the crude motif with his hand if he catches anyone looking. The tattoo marks Paik as a man apart - someone to be distrusted, disparaged even.Back when Paik got it, the tattoo was a badge of pride. Not anymore. Not in South Korea. That's because the tattoo is the logo of the North Korean Communist Party. It brands Paik as a defector. He might as well have a big "D" on his forehead. Making friends is hard enough. Finding a wife is next to impossible. "It's difficult to meet girls," Paik confides. "They aren't eager to marry North Koreans."

Defectors once got a lot more respect - even though they were used as propaganda pawns. When the Cold War was at its most frosty, defectors were paraded around like long-lost cousins. To be sure, there was always a deep undercurrent of mistrust - the paranoia between the sibling rivals knew no bounds - and the men and women who fled North Korea for the South always had a hard time fitting in. But these days, unless you're a big-name defector with juicy strategic information to impart, the red carpet is most decidedly not rolled out.

Until recently, South Koreans were praying for the collapse of the North Korean regime - and the reunification that would inevitably follow. Today, with the South mired in a recession, such yearnings are giving way to flinty pragmatism. Gradual unification, yes. A sudden German-style collapse, with the attendant social and economic costs, no thanks. The trouble is, as the North continues to starve itself to death, the trickle of defectors is becoming a stream. Five years ago, less than 10 a year went South; in January alone 17 arrived. While the numbers remain low compared to exoduses elsewhere, North Korea's isolation makes the situation unique. Defectors require intense debriefing and indoctrination - and even then they feel like outcasts.

The South Korean government estimates as many as 3,000 Northerners are hiding in China, waiting to make the dash to freedom. Defector support groups say the number is 100,000 or more. Lots of defectors nowadays are leaving the motherland not for political reasons, but just to stay alive. Hence, few seem even marginally special in South Korea. They are perceived as a liability - economic rather than political refugees.

Meantime, the 762 defectors officially living in the South are increasingly bitter. Nearly half are unemployed, and many turn to crime. Seoul prefers not to talk about it, but an intelligence officer says a fifth of defectors have committed crimes. Over the years, a handful have killed themselves; others have made desperate attempts to return to North Korea, where they almost certainly would be jailed or executed. Earlier this year, a group of defectors filed a suit against the government, seeking damages for alleged human-rights violations.

"Expectations are high when defectors come from the North," says Dr. Lee Keum Soon, North Korean specialist at the Korean Institute for National Unification. "They think it will be paradise. But they suffer so many things. Their education is different. There are language barriers, and social ones, too. Life isn't what they expected.

FEAR OF FREEDOMD

EFECTORS, OF COURSE, ARE not created equal. How they are received in the South depends on who they were in the North. High party officials get limousine service and fancy apartments; regular folk, on the other hand, are stuck out in the Seoul suburbs and pretty much forgotten. Defectors like Lee Min Pok.Lee took a roundabout route South. Roundabout being the only way, unless the defector

is sufficiently special to hole up in a friendly embassy - or has a death wish. The Koreas

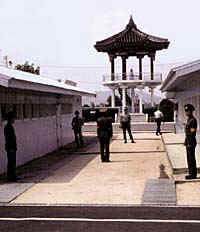

are divided by the world's most impenetrable imaginary line. Skirting the

38th Parallel, the 250-km Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) is draped with barbed wire, laden with

land mines, patrolled by more than a million armed men. In the nearly half-century since

the Koreas were split by a civil war that claimed over two million lives, only a

sprinkling of people have crossed a line that cuts like a knife wound across the

peninsula's midsection.

impenetrable imaginary line. Skirting the

38th Parallel, the 250-km Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) is draped with barbed wire, laden with

land mines, patrolled by more than a million armed men. In the nearly half-century since

the Koreas were split by a civil war that claimed over two million lives, only a

sprinkling of people have crossed a line that cuts like a knife wound across the

peninsula's midsection.

The most common route for defectors is to China, then to a third country where refuge is arranged, usually South Korea. Lee went this way, fleeing his hated homeland in June 1991. An agriculture worker often dispatched to the provinces, he bluffed his way past guards with an alibi about doing plant research along the border. Lee swam across the Tumen river to China, but wasn't free yet. Chinese troops patrol the 1,200-km frontier, under orders to return escapees to Beijing's old ally. Local villagers are paid for each North Korean they turn in. Lee played a deadly game of hide-and-seek. Even today, he trembles with the retelling and refuses to relive the worst details.

He was captured, turned over to North Korean guards and put in one of the many detention centers along the border. Lee, now 41, says he was beaten and starved. Others are not so lucky. Some, according to recent defectors, are shot as an example. Lee told his captors he had accidentally strayed across the border. Still, he spent months in jail. Upon release, he immediately bolted again.

Lee again crossed to China and this time blended in with the Korean community on the border, working odd jobs for a year. With his savings, he set off for Russia. At the frontier was a wide river. Lee was exhausted, but didn't think of turning back. "I swam across, wrapped inside an inner tube," Lee recalls. "It took days to get up the courage. I thought I'd die for sure."

Today Lee lives with his Southern wife and son in a soulless apartment tower on Seoul's outskirts. He has no job, and every time he ventures outside Lee is reminded of who and where he is. The street signs, the dialect, the knowing looks - they all scream the same thing: You are foreign. You don't belong here. And he knows the South didn't want him in the first place. Officially all defectors are welcome, but to get in Lee had to file a human-rights complaint with the U.N. in Russia. Tens of thousands of defectors in China are likewise in a no-man's land. Neither Russia nor Beijing want to upset long-standing ties with Pyongyang, which considers defectors traitors and demands them back.

Some defectors sneak in; others make a splash. Choi Hyun Sil captured headlines worldwide in 1996 when she arrived from the North via Hong Kong with 16 relatives - the largest group defection ever. It was the first time Choi had been on a plane. "It was wonderful to fly in the air," exults the 60-year-old grandmother. Other adjustments were more perplexing - the media's vociferous criticism of the Southern government, for example. Even the size of buildings. "When we lived in North Korea, they told us our hotels were the biggest in the world,"chuckles Choi's daughter, Kim Myung Sook, 35. "Here Isee a building, and Iget dizzy!"

The tattooed Paik and his friend Choi Keum Chul escaped via Russia, where, like thousands of Northerners, they worked as contract laborers. By the end of their three-year contract, Paik and Choi had met a South Korean missionary in Moscow. He arranged their escape. Choi left behind a wife and two children. "They are probably in prison, or dead - just because we had contact with this man," he says. "I would have been under suspicion as an enemy of the state. I couldn't go back." Today he and Paik make a living in Seoul selling Northern dishes that Paik says his grandmother served the late Great Leader, Kim Il Sung. Paik was a star soccer forward in the North; just one team will have him down South - a defectors-only squad. Scoring off the field with the ladies, though, remains a challenge.

People have various reasons for fleeing. For his part, Jang Hae Sung grew weary of shoveling lies as a radio reporter in the Phony People's Paradise. He recalls that a year after Kim Il Sung died in 1994, he was ordered to check out a report that thousands of swallows were bowing reverently at a spot the Great Leader had once visited. Jang knew the story was bogus but he had to go anyway. Only 20 of the station's cars had gasoline. "We had to take the gas from all the cars and put it in one car and drive there." Needless to say there were no genuflecting swallows. Increasingly embittered by the lies he was telling, Jang began discussing North Korea's shortcomings with a friend. When security police took his pal away, Jang fled to China and worked in a coal mine until he had saved enough to head South.

Similar hopes of finding a normal life is what brought Kim Hye Young, current darling of the defector circuit, to South Korea last August. A rising star in Pyongyang, she appeared in such films as Female Medical Doctor and plays like Strong and Righteous People. Movie actresses are favored by North Korean head honcho Kim Jong Il, who made films while climbing the rungs to Dear Leaderhood. But Kim Hye Young's parents felt her career would be stifled in the North, where pretty women often become pleasure girls for senior cadres. When Kim discovered her parents planned to take the family South, she cried and cried. "We begged to go back," says the 23-year-old actress. A harrowing seven-month ordeal followed. Kim spotted danger in every shadow. "I can't describe how scared I was. I had nightmares, horrible dreams." The family of five moved often in China, ropes hanging from windows in case they had to flee police. The petite film star says she lost 5 kg.

SHOW US THE MONEY D

D

Hwang wasn't alone. Months before and after, North Korea suffered a string of high-level defections. Diplomats fled missions in Paris, Cairo, Rome and Zambia. A few months previously, Lee Chul Soo flew over a North Korean MiG-19 fighter. The exodus had begun - and today Seoul is cautiously weighing the burden of the North's imminent collapse. The cost could easily run into the trillions of dollars. One study suggests that even if Seoul invests $750 billion in the Northern economy, after 20 years wages in the North will still be barely half those of the South.

The unease is palpable at the unification ministry. "There is a limit to what this government can do," admits Bae Dae Wo. He heads the ministry's support services section; it houses and helps train defectors after their release from the initial six months of detention and interrogation. Bae admits the system is being severely tested by all the new arrivals. The tab is already enormous. After the initial custody period, defectors are secretly resettled. Seoul pays for housing, as well as security for three years, or more. In the case of celebrated defectors, the protection can be indefinite. With good reason. Three days after Hwang's arrival, another prominent defector was murdered, possibly a reprisal by Northern hit squads. Hundreds of infiltrators are believed to be sunk in deep cover in the South.

Then, there is the cost of job training and community assistance. Topping it all off are resettlement fees. These ranged above a million dollars per defector in the old days, and nobody regrets it. The Koreas were on a war footing, and the defectors brought military and political secrets that helped shift the balance of power between the two adversaries. The first pilot to bring a MiG got $1.7 million.

But when Kim Il Sung died and the migration pace picked up, the one-time payments were

cut from 75 million won per defector to an average of 15 million won ($18,700). Not bad

pre-Crisis, but the currency's devaluation has since trimmed the grant to about $13,000.

Even a recession-minded government realized this was too low. Starting January, the grant

was boosted to 35 million won ($29,000).

But when Kim Il Sung died and the migration pace picked up, the one-time payments were

cut from 75 million won per defector to an average of 15 million won ($18,700). Not bad

pre-Crisis, but the currency's devaluation has since trimmed the grant to about $13,000.

Even a recession-minded government realized this was too low. Starting January, the grant

was boosted to 35 million won ($29,000).

That didn't placate all the defectors. In January, a group of them accused the government of torture. "When we arrive at the airport, we are given flowers and have a photo session for television and the newspapers," said Han Chang Kwon. "Then we are taken by van to an interrogation center. They strip off our clothes. They insult us with crude remarks. They beat you like a dog with sticks."

Han heads the Free North Korean Association. In January, he and eight others filed suit against Seoul, alleging grave human-rights abuses. It's a landmark case, the first lawsuit ever brought by defectors against South Korea. Lee Min Pok is among the plaintiffs. "I came on the plane from Moscow," he says. "They gave me no rest, but started the interrogation immediately. They used rude language and shouted at me. They called me human trash for leaving my family. We all feel sad about leaving our families. This was putting salt in my wounds."

Seoul initially shrugged off the suit, but was shocked by the subsequent publicity. Most officials discount the legal action as a cash-grab. "These people are greedy," one says bluntly. "They came as our guests, and we have taken care of them all this time. Now, they are using publicity to blackmail us for more money." Lee retorts: "This suit isn't about money. Never. I came here for equality and fair treatment. That's why I left North Korea." Still, the timing is poignant. The complaints come after Seoul boosted payments for early defectors but didn't increase them to those who arrived between December 1993 and the end of last year. All nine plaintiffs showed up during that period. As for allegations about the unfriendly welcoming committee, such interrogations have been going on for years; no one complained before.

Lim Young Wha, the lawyer handling the case, spews human-rights rhetoric, but even he acknowledges that the suit is really about money - a one-time payment of 20 million won ($16,400) apiece. And he admits victory is far from assured. The suit surely riles President Kim Dae Jung, a long-suffering political prisoner who challenged Seoul's dismal human-rights record in the past. Kim acknowledges that the security laws are draconian, and his government plans to make them more defector-friendly. Like practically all policies dealing with Northerners, the legislation is a holdover from the Cold War. Technically, the two Koreas are still squared off in the world's longest-running war.

At the same time, the lawsuit has focused attention on the defectors' plight as never before. "They lived all their lives in a different system, and now, here they are, a new language, new customs and no jobs," says an intelligence officer. "It's very difficult for them." Indeed, Northerners must be taught how to do the most mundane tasks - mailing letters, using the telephone, riding the subway. Their induction into the South's capitalist society is made more difficult because defectors are kept largely isolated until the debriefing period is over. The only person they see is their security minder. That worked fine when most defectors were single, skilled men who could be retrained relatively easily. Now, defectors are more often farmers and laborers. "We deal with older people and large families," says Dr. Lee. "It's much more difficult." Two years ago, she participated in a pilot program that introduced Northerners more quickly to their new society. Placing defectors with Southern families, for example, produced positive results, Lee says. But the government won't okay it, citing security concerns.

Still, authorities are clearly rethinking the defector dilemma. Kim Jung Tae, head of the unification ministry's policy section, says a housing and training center for defectors is under construction. Seoul has been touting this for years, but Kim insists it will open by summer. Defectors will live together at the center, after the interrogation and detention phase, and receive an intensive introduction to Southern life.

COLD WAR RELICS TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE? Many people think so. The government employs hundreds of planners who endlessly research reunification issues. Decade after decade. Kim Jung Tae talks of new programs, including incentives to encourage businesses to hire defectors. But when pressed, he admits the talk is just that. Finally, in February, there was some action when the government launched a Defectors Friendship Society. About a hundred showed up at the inaugural dinner, including former radio reporter Jang Hae Sung. "There's so much to do," he says. "North Korea is a fascist state. People there have been told lies for so long. We must tell them the truth. That's the most important thing."Jang poured out the truths from the podium, pounding his fists for emphasis. He spoke rapid-fire, recalling his radio days in Pyongyang. Others detailed the terror and tyranny in the North. It was like any rally in the old People's Paradise, only this time, featuring pro-freedom propaganda. Seoul footed the bill and gave gift packages to defectors. Inside were souvenir pens of the new society and a copy of Hwang Jang Yop's book, I Saw The Truth of History.

The government even trotted out the elder statesman, anointing Hwang, 78, head of the new group. It was North Korean All-Star night. The old-timers began with cheers of "Mansei" - or "Hooray!" Then, they extolled the grand goal of unification. Hwang was stiff and tired. News reports say since reaching Seoul, he has retreated, spending time watching TV and reading. Still, he pledged his remaining energy to building bridges in the defector community. A wide segment was represented, including Lee Min Pok, the legal claimant. Han, the lawsuit ringleader, was notably absent. He had a good excuse; Han was in jail after allegedly breaking the arm of a fellow defector who wanted to take over his Free North Korean Association.

Also absent from the unity gathering was actress Kim, busy with post-defection appearances. She is a regular on TV talk shows these days. Even as she takes speech lessons to lose her Northern accent, the film offers flood in. Marriage proposals, too. It's a far cry from North Korea, where she shared a dorm with other fledgling stars. Now she needs no fewer than two handlers. "She has very little time," one of them explains as Kim gets a facial a few days before unity night. She has to look her best; she's meeting Kim Dae Jung later that day.

In truth, the unity banquet is short on camaraderie. After the speakers finish, the meal ends abruptly. There is no friendly chatter. Dignitaries dash off to waiting Hyundais. Left behind are the bewildered Not Very Important Persons, buck-toothed farmers and worn-down old workers. Average Kims. A mob of reporters swarms Hwang, but security forces shoulder him past. Will he at least make a quick comment? Looking sad and drawn, he tells Asiaweek: "There is no one question. It would take all day."

Indeed, the defector problem is complex. That's partly because of all the security and economic issues. And not just for the Koreas, but all the other players, too - Japan, America and, most important, China. That's the big picture. But the real complexity lies in the lives of all the different defectors, not a community at all, but individuals from all spheres of activity. With different goals and dreams. "Defectors complain that they are treated differently," says Dr. Lee. "In some ways, it's true. Here [in the South] it's more a question of social class. North Koreans come here with a great sense of social equality. They also come here thinking they are special. The reality is, the political value of defectors is not as high as before."

Nobody knows this better than the unusual man who is last to leave the unity banquet. Unusual, because he has seen things from both sides. First as a defector to North Korea, where the Seoul native went after studies in Germany. He returned to the South in the mid-1980s, leaving behind two daughters, which clearly grieves him. "I was a Marxist," he says. "Ha, ha, ha. Now Marx is gone. It's all gone. Finished. Ha, ha, ha." And he adds sadly: "Look at us. We're relics of the Cold War."

![]()

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter based in Hong Kong, who roams the region for a wide range of publications, including Asiaweek, which ran this cover story in April 1999. Ron Gluckman has been on both sides of the Korean DMZ, so he has seen the tragedy of the division from both sides. Have a look at some of his stories from inside the Hermit Kingdom, by turning to the index for North Korea.

![]()

To return to the opening page and index

push here`

![]()

[right.htm]