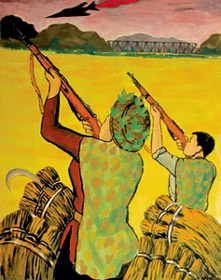

Revolutionary Art

During the Vietnam War, they painted for political purposes, to raise spirits, and troops for the fronts. Largely forgotten in peace time, the artists who produced Vietnam's vibrant propaganda posters are celebrated in "Dogma, Morale From the Ministry."

By Ron Gluckman / Ho Chi Minh City

HUANG HAI SPUN AROUND, cheerfully pointing out paintings at the exhibition. “That one is mine,” he said. “And that one, too.”

He hadn’t seen any of his paintings for decades, and was flabbergasted to find his art had someone survived the war years.

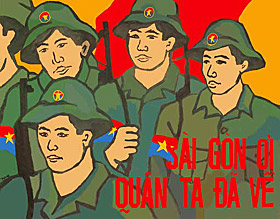

Pham Hoc Hai was likewise surprised to

spy, hanging from a wall, “Liberation of Saigon,” which he painted in April

1975. “I had no idea it still existed. I’m so excited to see it.”

Pham Hoc Hai was likewise surprised to

spy, hanging from a wall, “Liberation of Saigon,” which he painted in April

1975. “I had no idea it still existed. I’m so excited to see it.”

Largely lost to the world - and the artists themselves - for decades, these works and scores more from the Vietnam War period, have been revived in “Dogma - Morale from the Ministry,” a richly-annotated coffee-table book of propaganda posters from the 1960s and 1970s.

Few have ever been seen by the outside world, and most were forgotten here long ago, part of an unique art form that flourished – and faded – with the fortunes of communist revolutions last century.

During the Vietnam War period, propaganda artists like Mr. Huang and Mr. Pham not only created works to inspire the masses, but often transported them by bike, in battle conditions, to distant villages. Paper and ink was in short supply, presses practically nonexistent. Works were continuously reproduced by hand on the sides of buildings, trucks, even trees.

Hence, originals remain rare, prized by collectors who praise Vietnam’s stark style of propaganda as distinct from that churned out in other communist countries.

But as modern Vietnam continues to prosper, this art seemed destined for the dustbin of history. Rescue came from odd quarters: four foreigners, all British, all longtime Vietnam residents.

“We really didn’t do it to commercialize

these works in any way,” says collector Dominic Scriven. “We felt they were

extremely important, as art, as examples of the propaganda genre, as historical

records. We wanted them to be seen.”

“We really didn’t do it to commercialize

these works in any way,” says collector Dominic Scriven. “We felt they were

extremely important, as art, as examples of the propaganda genre, as historical

records. We wanted them to be seen.”

Scriven is the driving force behind “Dogma,” sanctioned by the government and printed in Vietnam, currently the only point of sale except online at www.dogmavietnam.com, where reproductions can be viewed and ordered.

But Mr Scriven says distribution deals are in the works for Europe and America, and he plans to exhibit the art later this year in Hong Kong.

For Mr. Scriven, merely seeing the book in print is a remarkable achievement. Founder and director of Dragon Capital, the country’s first and largest foreign investment fund, Mr. Scriven is a capitalist, but perhaps one with Vietnamese characteristics.

Resident of former Saigon since the early 1990s, he is well known for his outside activities. The purchase of vacation property some years ago on the then-undeveloped island of Phu Quoc evolved into the country’s first eco-resort. More recently, he launched the conservation group, Wildlife At Risk.

And, always, he avidly collected propaganda posters. His collection totals over 500, quite likely the largest in the world. He refuses to discuss value, but dealers nowadays ask hundreds, even thousands of dollars for originals. Until a few years ago, they could be had in galleries and junk shops around Vietnam for $50. Now you rarely see original works.

Not so at Dogma, a gallery opened by Mr. Scriven mainly to display some of the art from his growing collection. “I never wanted to sell them, but people saw them and wanted them.” Copying originals was the answer, spawning a small business in posters plus souvenir items like T-shirts and coffee mugs.

The book naturally followed, but took a

year to put together. Much of that time was spent simply tracking down artists,

detective work done by journalist Lucy Forwood. Fellow British residents of Ho

Chi Minh City, Jonny Edbrooke and Robert Speechley handled design and graphics.

The book naturally followed, but took a

year to put together. Much of that time was spent simply tracking down artists,

detective work done by journalist Lucy Forwood. Fellow British residents of Ho

Chi Minh City, Jonny Edbrooke and Robert Speechley handled design and graphics.

Even with the posters in hand, Ms Forwood faced a difficult task. Few works were signed. “Most painters didn’t see themselves as artists,” explains Ms. Forwood. “They were soldiers, dedicated to the war effort. One told me his job was in production - not of art, but soldiers for the front.”

Despite decades of reform, the art form is still in vogue with the government, which papers boulevards with the latest propaganda campaigns that recall the spirit of the 1970s, when posters proclaimed: "Our Army is a Heroic Army!" “Determined to Defeat the American Invaders,” and "Increase Food Stocks! Grow more Potatoes!"

But enthusiasm for the form isn’t widespread. “Young Vietnamese are bored with it,” Ms. Forward notes.

“Dogma” may not change that, but it does

preserve art of a historic period. And it may bring the aging artists overdue

recognition.

“Dogma” may not change that, but it does

preserve art of a historic period. And it may bring the aging artists overdue

recognition.

Mr. Scriven thinks the appeal is neither limited to Indochina nor propaganda fans. “There is a resonance, especially nowadays, with the situation in Iraq.”

His favorite posters convey universal themes: “The World Must Be At Peace” and “Nothing is More Valuable Than Independence and Freedom.” Still dogma, of a sort, but worth thinking about.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who is based in Bangkok, but who roams around Asia for a number of publications, such as the Wall Street Journal, which ran a shorter version of this story in July 2006.

All images are of posters from the book, courtesy

www.dogmavietnam.com

except bottom photo: Ho Chi Minh City during government meetings March 2006 by

Ron Gluckman

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]