United Nations of Outcasts

Each year, the world's unrecognized and repressed states gather at a summit where they share hopes, passing motions that nobody heeds, trying to protect human rights that continue to be trampled. For these Wanna-Be Nations, a group that grows larger by the day, there is no New World Order, only the same old shrugs and silence

By Ron Gluckman / the Hague, Netherlands

T

HE PRESIDENT BECKONS ME INTO THE ROOM. Pointing to a seat, he starts talking before I’m even settled. He describes the plight of his people, and their progress under his rule. Tea spurts from a plastic kettle as the rhetoric flows. None of the cups match, and mine is chipped. President Issac Chishi Swu is dressed in an ill-fitting gray suit and there is a

thread-bare appearance to his entire regime. During a recent visit to Europe, no

motorcades awaited at the airport. Instead of state dinners, Swu spends lonely nights in

three-star hotels. His entourage consists solely of Thuingaleng Muivah, vice president and

general secretary of his party. Often, they share hotel rooms. After a decade in power,

neither can claim many perks beyond an assortment of passports, none of which bears their

own state seal.

President Issac Chishi Swu is dressed in an ill-fitting gray suit and there is a

thread-bare appearance to his entire regime. During a recent visit to Europe, no

motorcades awaited at the airport. Instead of state dinners, Swu spends lonely nights in

three-star hotels. His entourage consists solely of Thuingaleng Muivah, vice president and

general secretary of his party. Often, they share hotel rooms. After a decade in power,

neither can claim many perks beyond an assortment of passports, none of which bears their

own state seal.

That’s because the People’s Republic of Nagaland exists not on maps but mainly in their imaginations, and that of nationalists in northern India and adjoining parts of Myanmar and Assam. Other groups claim to represent the four million or so Nagas, but Swu says his government has been in charge since 1956. Still, to most of the world, 68-year-old Swu is really President of Nadaland, of nothing.

His presidential routine only reiterates his insignificance. In Europe, Swu sits in embassy lobbies, awaiting low-level officials. Even a new truce with India, where Naga rebels have taken to blowing up trains in the latest phase of a conflict going back almost a half century, receives scant press. Yet Swu and Muivah remain undeterred by the world’s indifference to an independence movement that has consumed them; in their 60s, both joined fresh from high school.

"This has been our entire life," admits Swu. Then, their European visit at an end, the aged revolutionaries trundle off to the airport, bound for Bangkok, where both live as exiles. The president and his vice carry their own bags and fly economy class. Nobody notices.

So it goes with loads of other world leaders that the world doesn’t recognize: princes from Persia, sultans from Sabah, khans from Central Asia’s lost empires and exiled rulers of nearly every inhabited rock in the South Pacific. India alone claims scores of royal families from countless forgotten kingdoms.

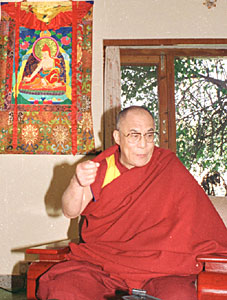

Some lands fall in and out of public favor, such as East Timor, East Turkestan, Kashmir and the Kurdish areas. A few capture the world’s attention, largely due to dynamic leadership, like the Tibetan cause gets from the Dalai Lama. For the rest of the globe’s fractious, seemingly fictitious wanna-be republics, the world is content to look the other way, except when flames of war fan these odd lands into the headlines. That’s what happens in Chechenia, Abkhazia or Bosnia. But what of less contentious sites, which may simmer in rage outside the world’s attention span for years, never quite rating the CNN hourly update?

"It’s extremely difficult for us to articulate our issues," admits Suhas Chakma, coordinator of Jumma People’s Network, which helps the indigenous people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. High in the mountains of Bangladesh, sandwiched between India and Myanmar, the isolated Tracts are home to over a dozen tribes. Largely left alone by the British, they have fared far worse under Bengali rule.

Bitterly protested resettlement policies have sent half a million Bengalis into the Tracts, where cultivable land is scant. The migrants have upset the harmony amongst the Tracts’ mainly Buddhist, Tibetan-Mongol descendants, who now comprise half the population of their own land.

"We have no hatred of the Moslems," explains Chakma, "but we are distinctly different people." He likens the situation to that of the Nagas, where nationalists opposed any union with India. "We never wanted to be a part of Bangladesh, or Pakistan."

Chakma works for an unrelated human rights organization in Delhi, donating three hours daily to the Chittagong cause. He has been involved for a decade. "In some ways, things have grown worse," laments Chakma, who roams the world, trying to woo opinion to the Hill cause. Interest is slim. "It’s frustrating," he says. "We are a small people, only a half a million. And the Hill Tracts aren’t East Timor, or Tibet."

Bougainville, an island in the Solomon Sea, likewise has neither Nobel laureate to galvanize global appeal, nor the worldwide network of advocates that keep Timor and Tibet on the international agenda. Yet Bougainville has started to appear on the world’s agenda. A protracted guerrilla war attracted little notice until a scandal hit the island’s colonial ruler, Papua New Guinea. But credit must also go to Bougainville’s not-so secret weapon, Martin Miriori.

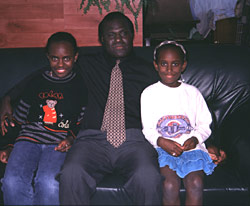

This freedom fighter won’t be found in the teeming jungles of the battlefield

telecasts, but up three steep flights of steps in a cold attic, atop a welfare flat in The

Hague, Holland. Here, with donated computer equipment, fax and phones, he keeps humanity

tuned to his island’s ire. His days regularly begin at dawn, running 18 hours or

longer. The phones rarely stop ringing. For Miriori, a charismatic black man with a

glowing, toothy grin, exhaustion leads to exhilaration. In his field, he notes heartily,

you want peace, but never quiet.

This freedom fighter won’t be found in the teeming jungles of the battlefield

telecasts, but up three steep flights of steps in a cold attic, atop a welfare flat in The

Hague, Holland. Here, with donated computer equipment, fax and phones, he keeps humanity

tuned to his island’s ire. His days regularly begin at dawn, running 18 hours or

longer. The phones rarely stop ringing. For Miriori, a charismatic black man with a

glowing, toothy grin, exhaustion leads to exhilaration. In his field, he notes heartily,

you want peace, but never quiet.

Miriori hasn’t had a holiday since making his dramatic debut on the diplomatic circuit in Europe in 1996. Although Miriori spent five years as the Bougainville Interim Government’s diplomatic chief in the nearby Solomon Islands, he rarely chatted with leaders outside the tight circle of small Pacific island nations. That changed soon after his house was firebombed. Miriori fled with wife and four children. Many nations offered sanctuary; Holland became home.

The reasons are familiar to numerous rebels who have taken their causes to the Netherlands, turning the nation into a hotbed of autonomy activism. Foremost is the central location, ideal for lobbying powerful European officials. Another attraction can be found by following Miriori on a jaunt through the diplomatic quarter of the Hague. Making the rounds in dark suit and tie, he regularly seeks support for this United Nations resolution or that human rights petition. Often, though, he strolls past the flags fluttering on tree-lined Javastraat.

Across from the Polish embassy, he enters a modest three-story block and instantly is buoyed by a sense of belonging only refugees know. He smiles while scanning a lobby draped in flags, but ones rarely seen anywhere else: the banners of the Batwa of Rwanda and Cordillera of the Philippines. East Timor and East Turkestan are here, along with the Acheh, West Papua and South Moluccas, of Indonesia. And, alongside the colors of Tibet, Tuva and Tartastan, Miriori spies the blue, green, red, white and black of his beloved Bougainville.

This odd assembly of flags, many outlawed at home, adorn the headquarters of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO). Like an United Nations of Outcasts, the UNPO assists the multitude of people scattered from Abkhazia to Zanzibar who claim no say in world affairs. Mostly unheard of, taken together they are a formidable group, 100-150 million people who are often worse than stateless; many are persecuted by their own state.

"The exact number really isn’t important," says Michael van Walt van Praag, founding general secretary of the UNPO. "What is important is that there is a significant number of people who feel left out, who aren’t properly represented in world bodies, and who feel they have no way to participate in world affairs."

Much global tension stems from this oversight, he says. "Wars nowadays are rarely between nations." More often, conflicts involve civil war, insurrection, or repression by governments of their own citizens. Victims rarely receive even the tardy international aid given Bosnia. "The UN is designed to resolve conflicts between states, not within them," says Van Walt. "It’s like a club of states." And there is rarely room in the club for those contesting the conduct of its members.

Into the void steps the UNPO, which represents 50 fledgling states or peoples left in the cold. They are a diverse lot, from the poor tribes of Chittagong Hill Tracts to the wealthy Taiwanese. Included are ethnic groups like the Maohi of Hawaii, Australia’s Aboriginal, and the Mon and Kerenni of Myanmar. Big or small, conquered or colonized, the UNPO makes no distinction. All these far-flung people have in common is an unfulfilled will for self determination.

Not all the world’s forsaken tribes speak in unison. A fourth of members want independence, while the rest eye autonomy, religious or cultural recognition, or land rights. The diversity lends strength, says van Walt, likening the group to a trade union confederation. "Many of us want to meet the same people, and share the same struggle," adds Miriori. "It makes sense to work together."

Besides connecting a network of autonomy activists, the UNPO also publicizes their causes, especially during critical periods, when members face an outbreak of violence, or its threat. The Urgent Action Unit spreads information about the crisis, and coordinates appeals to world bodies.

Scanning the UNPO worksheet is like revisiting the world’s hotspots: Abkhazia, Armenia, Kurdistan, Chechnia, Tibet, East Turkestan, Bougainville, Crimea, East Timor and Macedonia. Nearly everywhere there has been trouble, the UNPO has been involved, working to unravel the conflict. Normal assistance includes legal advice and training in fields familiar to diplomats, but otherwise unknown to leaders of fledgling states. "The UNPO has been invaluable," says Miriori.

Bougainville was a founding member in 1991, but the UNPO’s roots actually go back much further, to Asia. The concept was conceived in the mid-1980s by three opponents of Chinese imperialism: Van Walt, longtime lawyer for the Dalai Lama, Tibetan activist Tsering Jampa and Erkin Alptekin, a leader of the Uighurs of Xinjiang Province. The latter’s plight explains the logic of the union.

The latest series of bombings in China’s western Xinjiang Province pushed the region into newscasts in 1996, but revolt has been a constant for decades in the land known as East Turkestan during two brief periods of independence in the 1930s and 1940s. Since then, Muslims in Xinjiang have been persecuted by the Chinese rulers, says Alptekin, "not that the world paid ever much attention.

"There was an Eastern Turkestan Union in Europe. The aim was to lobby the western hemisphere, to promote our cause. But in those days, there weren’t many avenues," says Alptekin, recalling the founding days of the group that he later chaired, from his home in Wurzburg, Germany. The answer? An alliance with activists from Tibet and Inner Mongolia.

Although vast differences separated East Turkestan’s Muslims from the Buddhists in Tibet, they found many common causes. One was a fear about the increasing threat of violence in their lands, and the world’s apparent acceptance of this trend. "We saw Yassar Arafat welcomed to the UN when the Dalai Lama wasn’t even allowed in the building," notes van Walt.

Non-violence has been a key plank of the Dalai Lama’s approach during four decades

in exile; it’s also a main covenant of UNPO membership. Lesser-known groups in the

UNPO gain from the example of the Dalai Lama - the great superstar of autonomy struggles -

in many other ways.

Non-violence has been a key plank of the Dalai Lama’s approach during four decades

in exile; it’s also a main covenant of UNPO membership. Lesser-known groups in the

UNPO gain from the example of the Dalai Lama - the great superstar of autonomy struggles -

in many other ways.

They try to replicate his success communicating the Tibetan cause to the world, and they invoke his name often in press releases. But the link sometimes plays into the hands of critics who deride the UNPO as a western tool against developing nations. Mudslingers easily find other ammunition.

Members are assessed annual dues of US$1,000, but many have no means to pay. Even if all did, this would bring in just 10 percent of the current UNPO budget. Most comes from western governments and charities. And critics gleefully note the political connections of the UNPO founders: General secretary van Walt and deputy Jampa have been closely aligned with the Tibetan cause, while Alptekin spent 25 years with Radio Free Europe, beaming western propaganda to Turkic countrymen in China and the former USSR.

There is also a ring of post-colonial revivalism around the UNPO’s very base in Holland, where nearly a third of its members are represented. Unsurprisingly, many hail from Holland’s former possessions in Indonesia: the Acheh, West Papua and the South Moluccas. Representatives of other nearby islands, such as East Timor and Bougainville, also live near the UNPO office, which is in the Hague’s Archipel Wijk, or Archipelago district, where streets are named for isles of the old Indonesian colony: Celebes, Java, Lombok, Riouw and Borneo. Sheer coincidence, says Van Walt. When the UNPO formed, various cities were considered for its headquarters, including New York. The Hague won because of its European location and generous pledges of community support, he says.

Still, Holland prizes its standing as one of the world’s most conscientious countries, spending generously on human rights causes. A billion (US) dollars were expended upon various domestic asylum activities in 1996. Some of that money goes to the Foundation for Study and Information on Papuan Peoples (PaVo), a cultural group that helps Holland’s estimated 1,000 former Papuans. The money also helps to keep rebellion simmering in an Asian hotspot.

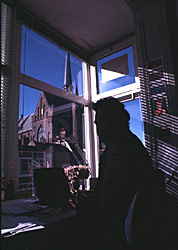

Insurrection might seem incongruous to anyone visiting the PaVo office in Utrecht. The second-story windows overlook majestic church steeples. Walls are lined by books and binders. It resembles an university study hall, and this appearance is enhanced by the two students sitting with office manager, Grace Roembiak - all in their 20s. The talk, too is college quality. About saving the world - starting with their part of it.

That part isn’t Holland, but western Papau New Guinea, where a guerilla war has been sputtering along since long before these women were born. Rebels oppose the huge Freeport mining operation on their island. In 1995, they nabbed over a dozen hostages. They want a free West Papau. That’s what Grace and friends Inaria Kaisiepo and Leonie Tanggahma call it. Indonesia calls the place Irian Jaya. And, since the Dutch left, the world has largely gone along.

"But that’s changing. Now, people know about West Papua," insists

Roembiak, whose working-class accent is but one contrast from her smooth-talking sisters

of this sovereignty campaign; only Roembiak has visited the homeland all three adamantly

insist should be free. Still, they share the same all-consuming enthusiasm. Kaisiepo has

been involved in the cause since a teen and continues to watch her studies slip. "I

try to go to class and study, but university isn’t my priority," she admits.

Boyfriends are also out. "I don't have a personal life anymore," says Roembiak.

"Everything is West Papua." Together, they work 150 hours per week to free West

Papua. None of them can speak the native language.

"But that’s changing. Now, people know about West Papua," insists

Roembiak, whose working-class accent is but one contrast from her smooth-talking sisters

of this sovereignty campaign; only Roembiak has visited the homeland all three adamantly

insist should be free. Still, they share the same all-consuming enthusiasm. Kaisiepo has

been involved in the cause since a teen and continues to watch her studies slip. "I

try to go to class and study, but university isn’t my priority," she admits.

Boyfriends are also out. "I don't have a personal life anymore," says Roembiak.

"Everything is West Papua." Together, they work 150 hours per week to free West

Papua. None of them can speak the native language.

That’s actually pretty common amongst the fervent campaigns of overseas activists. The internet hosts scores of web sites devoted to controversies around the globe. Democracy advocates of Myanmar, for instance, operate dozens of web and newsgroup sites, mostly from distant locations in North America, Europe and Australia. Still, westerners have no monopoly upon rhetoric.

A bumper crop of bravado can be found amongst Holland’s sad communities of refugees from the Moluccan islands of Indonesia. About 60,000 arrived when the ambitious young Republic of South Moluccas collapsed soon after its formation in the early 1950s. Few have assimilated. Instead, for four futile decades, the notion of going home has been nurtured for generation after generation.

"The South Moluccas will be free. I feel it, I know it," says Frits Waas, at home in his Moluccan enclave in Capellea’d’jssel, near Rotterdam. Seated around his living room are like-minded neighbors of varying age who repeat a similar refrain. Waas believes Indonesia will fall apart, "just like Yugoslavia." His parents came to Holland with the refugees that were housed, temporarily and tragically in a former Nazi concentration camp. Free housing was offered and the Moluccans moved enmass to new communities. Waas married a Moluccan neighbor; they live in the same government flat where his parents resided until their death. "I’ll never leave," he says, "not until the Moluccas are free."

Nearby lives Paul Tomasoa. He’s tall and handsome. And outraged. Dressed in natty leather coat, chain-smoking Marlboros, the young man angrily describes how he was robbed. Forty-five years ago. But 25-year-old Tomasoa acts as though he remembers the day. "Indonesia took our country, and the Dutch betrayed us."

This is surely not typical of most Moluccans, and certainly not those still residing in the impoverished islands, where concerns are more for a daily living than the bitter remembrances of their comfortable European brethren. In many ways it’s an odd contrast; in the sleepy, former Spice Islands, where change is slow, most Moluccans long ago adapted to the reality of Indonesian rule.

Yet, in Holland, entire communities of Moluccans refused to adapt, assimilate or move on. "Our grandparents came here and were told it was only temporary. That they would be going home again with Dutch help," says Tomasoa, who admits that he would never live in the Moluccas. "But that’s our country. We can never forget. We can’t betray our grandparents."

Tomasoa walks me around his neighborhood with his brother, Ferry, Jr. Both are members of the community security guard, Parang Salawaku, which means, in the old Moluccan dialect, sword and shield. People wave, not only from their yards, but inside the houses, too. It’s a serene site, but even without wire or walls, it's a ghetto.

Not that it’s not an ugly place. Far from it, in fact. The 150 homes sit in neat rows trimmed by greenery. The Moluccans, who are predominantly Christian, have their own church and a community center for dances and meetings. They try and maintain the spirit of the Moluccan Islands in an enclave measuring six by four blocks. Yet the enclave is largest among a network of Moluccan communities that meet to elects an exile government. Term after term, for decades, the candidates all make the same outlandish promise: Freedom for the Moluccas.

The frustration seems most tragic amongst the young. Two decades ago, the pent-up rage exploded into a series of violent actions. During a train hijacking in 1975, two passengers were executed in public view. By the time another train and an elementary school were seized 17 months later, the Moluccans had been branded terrorists; six were killed by Dutch troopers who stormed the school. Almost a quarter of a century later, there is little concern for the Moluccan cause, which whimpers along with an annual protest in the Netherlands. "Obsolete," is how one Asian scholar in Holland summed up the Moluccans.

"We can’t give up," insists Ferry Tomasoa. "That’s why we can’t live like the Dutch. That’s why we stick together." Adds brother Paul: "That was the Dutch plan, that by the third generation, we’d forget the Moluccas and become Dutch. That was their biggest mistake. It will never happen."

Then, stopping at the edge of his tiny, neatly-trimmed ghetto, Paul says with a sweep of his arm, "This is the South Moluccas. This is my country."

An hour away from this miniature Moluccas, the mood is more upbeat. At the PaVo office, a student from West Papua is visiting, and the sisterhood swings into high gear. Calls are made to reporters. Releases are drafted to draw attention to the latest crisis in the homeland, where a drought is killing hundreds. Where the Moluccans are dug in, demoralized and bitter, the Papuans are enthusiastic, effervescent, seemingly undefeatable.

"Oh, we know we will win," Kaisiepo says matter of fact, but without a smugness. "For us it’s not so much a question of whether Indonesia will fall apart, but what will come next, what we can do to prepare for that."

Kaisiepo exudes confidence bellying her 26 years. No wonder. While still a teen, she serenaded the UN with her message. Part of the conviction is inherited. Her father was longtime leader of Papuan activists and her grandfather an official in the Dutch days. Tanggahma is another second-generation activist. Her father headed West Papua’s exile Revolutionary Provisional Government. "This does get in your blood," says Tanggahma. "You grow up with it. The work becomes your life."

Keeping the faith isn’t always easy. Alptekin fled his homeland in the face of the Communist takeover in 1949. His father had been a top official in both the Nationalist and the briefly independent governments of East Turkestan. After a half century in exile, this Muslim leader draws strength from the example of others. "I tell my people to look at the Jews. They waited thousands of years, living amongst oppression. Yet they never gave up their culture, or their faith."

Chakma also takes solace from the Jewish people, particularly Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. "Look at him. His work has never been easy, but he gave it his entire life, because he believed in the justice of his cause."

That’s one thing that all UNPO members have in common - an unshakable belief in the justice of their cause. Swu recounts the long list of injustices rained down upon the Nagas, almost exactly as Chakma describes the plight of those in the Hill Tracts. The grievances are enormous, gripping. While there is a common cause, the results range widely in a way that makes justice seem more arbitrary rather than absolute.

During a recent summer, the UNPO held its General Assembly in Estonia, itself a founding member of the UNPO and one of its greatest supporters. Estonia is also part of an elite group of five former members that have attained the ultimate goal: independence. Keynote speaker was another star of the UNPO, Nobel laureate Jose Ramos-Horta, whose prize has revitalized a floundering struggle in East Timor.

His reception underscored a vital point of the UNPO: not all autonomy battles are equal. "Timor is in the forefront now," says Jose Antonio Amorim Dias, East Timor’s European Representative since 1992. For much of that time, Dias, an unpaid Timorese exile, has subsisted on the handouts of friends. Early next year, though, he will likely become East Timor’s first official posted to Brazil, at the invitation of the fellow former Portuguese colony. Before the peace prize, Dias says, "Hortas would visit embassies and they would send out the number two or three. Now doors are open to us."

Peace prizes aren’t the only measure of acceptance in the pecking order of freedom fighters. Many activists believe that Bougainville will be the next cause on the world stage, and a visit to Miriori’s abode offers much affirmation. In many ways, it looks like any other working-class flat. The living room suite is imitation leather, while family photos crowd cheap framed collages. It’s warm and friendly, but also a home in which an exile could easily bunker down in bitter isolation. Instead, Miriori cheerfully taps out press releases on a new Hitachi laptop, then sends them on the new Canon fax. Keeping in touch with his brother, who leads the rebel army in the jungle is no problem. They chat by satellite phone.

The high-tech equipment, bought with donated funds, shows this is a trendy cause. This does not mean to diminish Bougainville’s battle for freedom, or the suffering its people have endured. Situated amongst the Solomon Islands, populated by Melanesians with whom the Bougainvillians share a close kinship, Bougainville is ruled by distant Papua New Guinea.

The exact course of events that created this firekeg of discontent would seem laughable if not so common during colonial times. Named by a French explorer, Bougainville was grabbed by the Germans and sliced away from the other Solomons, which went to the British in a treaty of 1899. After World War I, the territories were run by Australia, courtesy of a League of Nations decree. The island was occupied during World War II, first by the Japanese, then the Americans. Afterwards, it wound up back under Australian rule, this time as an United Nations Trust territory. When Papua New Guinea gained independence in 1975, Bougainville was part of the package. As in all earlier transactions, Bougainville wasn't consulted.

And the world never bothered to conduct any opinion polls or worry about the mood of the local population. At least, not until after copper was found and one of the world’s largest mines was established, then closed by disgruntled Bougainvillians, and Papua New Guinea mounted, with Australian assistance, a war that has claimed about eight percent of the island’s population.

Even then, nobody protested too loudly. Not until 1996, when the hiring of foreign mercenaries brought down Guinea’s government and elevated the island conflict into an international outrage. Now, talks are underway and regional powers like Australia are working hard to encourage resolution.

Miriori is no fly-by-night revolutionary. An economist by trade, he realizes, "Bougainville is hot because of the scandal over the mercenaries. That escalated Bougainville into international focus... It’s been an odd blessing in disguise."

But Bougainville, after all the UN petitions and pleading of the people, is the exception. Not all autonomy movements get so lucky. Not all ruling nations make such monumental blunders. For most, there is little hope.

At least, that was the case until the UNPO came along. Van Walt, who is taking leave of his general secretary post after seven years, remains modest about the group’s accomplishments. Clearly, though, the UNPO has focused world attention on various scenes of inhumanity. Human rights groups credit the UNPO with bringing to light the vicious repression of the Ogani in Nigeria. But these are the celebrated causes that get covered on CNN. The true value of the UNPO may rest in all the causes you rarely hear about, like the Cordillera in the Philippines of the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

These are the people who were never invited to join the New World Order. For millions like them, living in repression and desperate for recognition, the UNPO offers not only an ear, but a voice to the suffering. With all the chaos and competition on the world stage, it may not seem like much at times, but in a world already wracked with ethnic conflict, not to mention an estimated 5,000 minorities, the UNPO offers an alternative to endless new explosions of rage.

Ron Gluckman is an American journalist based in Hong Kong, who travels widely for Asiaweek Magazine, which ran a shorter version of this story in 1998. For more information on the Unrepresented Nations and People's Organization, see the web site for the UNPO.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]