POSTCARDS FROM THE BEACH

When Leo diCaprio landed on a serene Thai island, was it a countdown to the end of Utopia, just like in "The Beach"? Following a storm of controversy, the sand is left with the prospect of millions more footprints upon the world's most perfect beach

By Ron Gluckman /Maya Bay, Phi Phi Leh and Bangkok, Thailand

Pictures by David Paul Morris

(See also interviews with the author of "The Beach," Alex Garland, and producer Andrew Macdonald.)

I FOUND IT! THE PERFECT BEACH. Not just any sun-bleached shore, but THE BEACH. Set alongside a blue lagoon, in the perfect bay. Shielded from prying eyes by sheer cliffs on all sides. The ultimate beach. Sun, sand and sea. Paradise. Until recently, that is. Ever since Maya Bay, in Thailand's Phi Phi island chain near

Phuket, was anointed The Beach in the 20th Century Fox film starring Leonardo DiCaprio,

the spot has been anything but peaceful. And the perfect beach happens to be in a national

park, prompting allegations that officials are selling out Thailand's natural heritage to

a rapacious Hollywood.

Until recently, that is. Ever since Maya Bay, in Thailand's Phi Phi island chain near

Phuket, was anointed The Beach in the 20th Century Fox film starring Leonardo DiCaprio,

the spot has been anything but peaceful. And the perfect beach happens to be in a national

park, prompting allegations that officials are selling out Thailand's natural heritage to

a rapacious Hollywood.

Meantime, islanders disgruntled over missing out on a slice of the film's $40-million budget have clashed with islanders lucky enough to be on the payroll.

Swamped by the tidal wave of controversy and hype, however, is the movie itself - and what it will mean for Thailand.

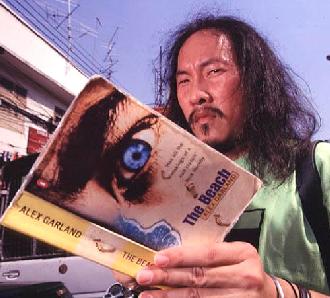

The film is based on British author Alex Garland's 1997 bestseller, also called The Beach. A kind of children's classic for backpacking hippies, the engaging utopian satire tells the story of a backpacker weary of overrun tourist spots in Thailand.

The chain-smoking protagonist, played by DiCaprio, follows a secret map to paradise among the palms, beside a huge pot field, and a blissful commune of like-minded individualists. They spend the days singing, fishing and smoking mounds of marijuana. Until it all falls apart.

To discriminating minds, the plot may sound far-fetched, inane fantasy. In fact, that was Garland's intention. He based the book on his own Asia wanderings and meant it as commentary on the folly of smug, young tourists, who call themselves travelers - a special breed more sensitive to the local cultures and locations they trample over.

He tells me:

"The Beach was meant to be a criticism of backpacker culture, not a celebration of

it."

He tells me:

"The Beach was meant to be a criticism of backpacker culture, not a celebration of

it."

Still, the book and upcoming film have created a sensation on the backpacker circuit, where the novel has become de rigueur for beach acolytes. Others complain that Garland presents Thais as one-dimensional, a charge that irks the 28-year-old author. "I think it's fairly obvious this isn't a book about Thailand," he grouches. "It's about backpackers."

Either way, The Beach has put a spotlight on the young travelers who descend on Thailand each year. Not everyone appreciates their contribution to the economy. One local writer unkindly refers to the young tourists as the "backpacker cult."

Other Thais are blunter still; they call them farang kee nok - foreign bird droppings. Yet Thai tourism officials insist the only bad thing about backpackers is that there aren't more of them.

And The Beach should bring them. The movie is a virtually certain blockbuster, since the same team that made the hip smash Trainspotting has cast international heart-throb DiCaprio in the lead role. Before long, millions of people around the globe will be lining up to see The Beach, and Maya Bay is destined to become the most famous stretch of sand in Asia, if not the world.

Even now, as I make an illicit landing on its unspoiled shores, paparazzi, Beach devotees and star-gazers gather on the other side of Phi Phi Leh isle. Looking for Leo. They swarm his hotel. They flood Internet sites, surfing for his schedule. Fanatics hire boats, motoring to Maya Bay, where cast and crew dock. If lucky, they see Leo before he dashes to and from the shoot.

I head there myself, later - for now, I relish my surroundings. After all, this is the most fought-over beach since the Americans wrested Iwo Jima from the Japanese during World War II.

My landing is unexpected. News reports had said the approach to the tiny bay was patrolled by the Thai navy. In reality, only a few members of the crew are present, taking a break. Today's filming is out to sea, where a helicopter and rubber boats circle a pretend Ko Samui ferry. Three decks are stuffed with scruffy, young backpackers, hired for a few days to portray . . . scruffy, young backpackers.

The reports also say a thousand-boats-a-day visit the island, looking for Leo. In several visits, I see a handful. Three Japanese women, giggling about how they have made five trips over to the dock. And a German woman, also a regular. "My name is Maya," she serenely intones. "Like the bay." A cosmic coincidence, she concludes. Destiny draws her toward Leo. She has come from Ko Samui, to give him a crystal.

The hoopla seems to consume the entire nation. In Bangkok, this same day, environmentalists protest outside the U.S. embassy. Wearing Leo masks and fangs. Brandishing signs that say: "Don't rape our beach." Demanding an investigation into Hollywood's invasion of the island park. The outcry has only increased since the film-makers found the perfect beach and made it, um, even more perfect! They touched it up with coconut trees and plastic flowers. Paradise.

AS PAPARAZZI SWARM PHUKET, where Leo stays, I head instead to Khao San Road. This 300-meter strip in Bangkok has become a legendary Mecca for freaks, like Goa and Katmandu. Overrated? Way so. Scores of cafe's serve up cuisine that pleases budget more than palate. Pizza and non-stop videos. And enough nose rings and tattoo parlors to equip a hundred carnivals. "The first I heard of the beach was in Bangkok, on the Khao San Road." That's the first line of the book. "Khao San Road was backpacker land," Garland writes. "The main function of the street was as a decompression chamber for those about to leave or enter Thailand, a halfway house between East and West."

But when East meets West, in real life, the West takes over. In Thailand, the tidal wave isn't just McDonald's and Pizza Huts and 7-Elevens, but also bootleg tape stalls, banana pancake stands and claptrap hostels. Hair braiders, sandal sellers and acres of sarongs and drawstring pants. Forget mysteries of the East. What I want to know is this: Why do Europeans, the minute they arrive in Asia, rush out to wrap their legs in the gaudiest curtains they can find?

This is the genuine opening scene for a multitude of backpackers flocking to Asia each

year. Exactly how many is anyone's guess. "There is no information specifically on

the backpacker market," says Seree Wangpaichitr, governor of the Tourism Authority of

Thailand. Yet more than 2.6 million tourists aged 15-34 arrived in the first 10 months of

1998. That's about 35% of all visitors. No wonder the governor opened a TAT information

booth two months ago, around the corner from Khao San Road - in front of the police

station, where dozing officers ignore the blatant smell of marijuana and other minor

offenses.

Seree can't say how many banana pancakes are flipped on Khao San Road, but he tells me: "Contrary to popular thought, backpackers are a good source of business. Their average stay is between one and two months. They are culturally sensitive, stay in small lodges, eat in roadside stalls and travel by public transportation. That means jobs at the grassroots level." Enlightened attitude or simple economics? Tourism has long been one of Thailand's biggest dollar earners and the pressure is on to push the numbers even higher. Long shunned by bureaucrats, tourist offices and visa officials, the Great Unwashed are now more than welcome - in Thailand anyway. Seree reckons many are the "corporate executives of the future."

Maybe, but try spotting the Masters of the Universe on Khao San Road. The hairy guy with the barb-wire tattoos inhaling a Styrofoam plate of Thai noodles? The Londoners with a full set of cutlery inserted in nose, ears, eyebrows? Or the individuals in dirty dreadlocks, wrapped head-to-toe in raw, white cotton? And let's talk about the drugs.

When the moon is full, the loonies take over Hat Rin beach, at the southeastern tip of Ko Pha-Ngan, an island north of Ko Samui. The flood of backpackers has turned Hat Rin's Full Moon parties into an international raving institution. For a time, Thai officials talked of suppressing the blatant Ecstasy-popping, but nowadays, travel agents in Ko Samui advertise day trips to the round-the-clock party. A recent issue of Metro, Bangkok's what's-on rag, even carried a Full Mooning guide, complete with dates, tips about transport and a section on drugs.

T

HE TRAVELER TRAIL IS a well-worn motherlode of cheap tickets, road advice and beer talk. But for real information, you need to hit the highway. The information highway. Dozens of Internet cafe's crowd Khao San Road, so the sensitive travellers can keep in touch with the western world while on their grand getaway . I log on, plug into the Leo-line and find a site devoted to The Beach. It's not in Hollywood, but rather is housed not far from Bangkok, at the Sriwittayapaknam School, in Samut Prakarn. An hour later, I'm at the school, surrounded by Thai students, aged 3-13. This is Leo's world. Updated daily, the site (http://come.to/thebeach/ ) is crammed full of gossip, cast lists, photos and shooting schedules. Changes are posted in real time, almost before the film company changes its mind. Hollywood is famous for flip-flops. In fact, film representatives later try to quiet the site, even as other reps enthusiastically refer reporters to it.

Students have put together 400 web pages on everything from Thai stamps to protocol for Thai temple visits. The latter followed Leo's trip to a wat. This week, Leo went to see kick boxing. Next day, that story was added to the site, along with information on boxing. "I see this as a real opportunity to teach people about Thailand," says teacher Richard Barrow, the man behind the Internet project. "Everyone is interested in Leo being here. In the first two months, the site was getting five hits per day." Then Leo arrived. "Now, we're recording 3,000."

Of course, true devotees don't drool over Leo web images. The hardcore head to Phuket. I find them hanging around the Cape Panwa Hotel, buzzing about alleged sightings. Leo signing autographs. Leo by the pool. Leo in a fling with a Thai massage girl. "Leo is used to it," says Andrew Macdonald, almost-equally besieged producer of The Beach. "He gets it all over the world. These silly stories about food-tastings, pregnant girls."

In reality, DiCaprio rises early and gathers with the rest of the cast and crew at a dock near the secluded hotel. Breakfast is served dockside at 5:30 a.m. Buffet-style. Coffee, juice, eggs and bread. "Leo's OK," says a driver posted by a dozen trailers that serve as transportation and makeshift dressing rooms. They're spare: TV, stereo, fridge, single bed, toilet. "He is pretty normal, not too much like a star. He doesn't say much, but he's friendly." By 6 a.m., two high-speed ferries take off for Phi Phi Leh. Forty-five minutes later, cast and crew approach the island. They land at a floating dock. DiCaprio is usually last to show. Rather than the newest - and youngest - member of Hollywood's exclusive $20 million-per-picture club, he looks more like any Khoa San kid: white singlet over baggy green shorts, slung low, with boxer shorts showing. Sandals or sockless loafers. A backward baseball cap completes his beach costume.

As usual, the Leo watchers are on high alert. Before he steps onto the dock, they buzz by in longtail boats. The star pays no attention when they wave, sipping a Coke or smoking cigarettes before ducking back inside a boat. Back at the Cape Panwa Hotel, the starstruck chase any link to Leo. After I make a phone call in the lobby, a middle-aged American woman rushes over to ask if I'm connected to the film. "You might think I'm crazy," she gushes after my denial, "but I just love Leo."

There are fans, and there are fanatics. And then there are followers. Leo claims them

by the planeload.  Some follow the followers. Shimomura Mami, 36, writes an Internet column

for Flix, a Japanese magazine. She has journeyed to Thailand with Leo-watchers Satoyoshi

Noriko and Kimura Rie. Ostensibly, Shimomura is on assignment to write a book, Followers

of Leo, set for rush-release in April. Yet the only followers she has spoken to have been

Satoyoshi and Kimura. The trio met last year on a Leo chatline. "We already know so

many Leo fans from the Internet," Shimomura says. "For this book, we'll mainly

write about our experiences in Thailand. It will be like our diary."

Some follow the followers. Shimomura Mami, 36, writes an Internet column

for Flix, a Japanese magazine. She has journeyed to Thailand with Leo-watchers Satoyoshi

Noriko and Kimura Rie. Ostensibly, Shimomura is on assignment to write a book, Followers

of Leo, set for rush-release in April. Yet the only followers she has spoken to have been

Satoyoshi and Kimura. The trio met last year on a Leo chatline. "We already know so

many Leo fans from the Internet," Shimomura says. "For this book, we'll mainly

write about our experiences in Thailand. It will be like our diary."

Don't expect a page-turner. None has visited Thailand before. They are here a week. The main action so far? A trip to Phi Phi Don, an isle near Phi Phi Leh. They hired boats to stake out Leo dockside, twice daily. Sightings are scant, as the filming takes place inland. "We don't swim, we only watch him come and go," says Shimomura. "It's quite exciting." Now, they stay at the Cape Panwa Hotel, paying almost $200 a night for the privilege of sleeping in the general proximity of Leo. The high point of their trip came the previous Sunday, the film crew's day off, when they actually visited Maya Bay. On a bed in the hotel room, they spill out their precious souvenirs: sand, shells and coral collected from the protected island.

E

NVIRONMENTAL PROTESTS MUDDIED THE waters of the perfect beach even before the shooting started. Yet hundreds of films, documentaries and commercials have been shot in the marine park previously. Geena Davis staged Cutthroat Island, a sort of feminist pirate flick, right in little Maya Bay. Back in the days of the original 007, James Bond actually came out and blew up an island in the park. That was before Western-style environmental consciousness washed over the dynamite-fishing grounds of the Andaman Sea, according to Ing Kanjanavanit, an outspoken opponent of the film. "I'm sick of this colonial crap, of Hollywood coming out here and taking advantage of a poor country. I'm tired of them shitting all over us." Adds Manit Sriwanichpoom, of the Artists Group for Democracy and the Environment: "Before you go to Maya Bay, be sure and get a postcard. You'll see how beautiful the island and the beach are. But the beauty is just a memory on a postcard now." Total hyperbole, but they have reason to be angry. They object to any alterations to

the landscape. And they fume about what they claim was the film's illegal approval. Their

key point is that, rather than go through regular channels to film in the park, The Beach

was given an exemption from the National Parks Act. This bans any change in the natural

state of the park, except on educational, scientific and tourism grounds. The government's

response? Silence mainly. As the protests grew in fury, the film-makers were left to

explain away the modifications. These include planting 60 coconut trees - scaled back from

100 - leveling a pair of dunes and clearing weeds. Nobody, they point out, complained

about the three to four tons of trash they carted away.

Total hyperbole, but they have reason to be angry. They object to any alterations to

the landscape. And they fume about what they claim was the film's illegal approval. Their

key point is that, rather than go through regular channels to film in the park, The Beach

was given an exemption from the National Parks Act. This bans any change in the natural

state of the park, except on educational, scientific and tourism grounds. The government's

response? Silence mainly. As the protests grew in fury, the film-makers were left to

explain away the modifications. These include planting 60 coconut trees - scaled back from

100 - leveling a pair of dunes and clearing weeds. Nobody, they point out, complained

about the three to four tons of trash they carted away.

Only later, much later, as environmentalists stirred the controversy to a boiling point, did Plodprasop Suraswadi, chief of the forestry department, answer the charges. When I drop by, he is still smarting from the environmentalists' scathing attacks. Although two suits designed to stop the film were earlier dismissed, a lawsuit is set for court next month. Plodprasop is one of five defendants, charged with breaking laws to protect parkland. "I don't mind facing the charges," says the Ph.D. ecologist. What bothers him is the vindictiveness of "left-wing extremists," many of them former students at the universities where he once taught. "Why do you do this to me?" he asked them after another vicious confrontation. "You treat me like an animal, a dead thing." Plodprasop says the greens are using Leomania to get attention. As to a donation made by the movie-makers, he says: "That's not a bribe - ridiculous!" The 5 million baht (about $135,000) will be used to establish a park station on Phi Phi Leh and patrols around the island.

Most islanders discount the protests as a silly stink raised by city folk. Then again, most are also profiting from the film production. Yet even environmentalists worry that extremists have targeted this film, and Leo, to draw attention to their cause - expending energy that could go to other campaigns, and better causes. Even a blind ecologist could score a bullseye on Phi Phi Don. Part of the same marine park as Phi Phi Leh, it has equally stunning beaches, bays and rock formations. Plus one thing Phi Phi Leh lacks. Inhabitants. Phi Phi Don is a chaotic sprawl of beach huts, cafes and shops. All-night rock blasts from the Rolling Stoned Bar, while reggae and disco lights flood the Jungle Bar, which sits on a hilltop painted with enormous murals of Bob Marley. That's down the palm-shaded dirt path from the PP Marijuana Shop. Phi Phi Don is more like Khao San by the Sea than parkland.

Backpackers aren't to blame, says Joe Cummings, who wrote Lonely

Planet's Thailand guide. He says industrial pollution, overfishing and a long history

of rampant logging, legal and illegal, have done the real damage to the environment.

Cummings' guidebook even warns tourists to steer clear of the Phi Phi islands. "The

park administrators have allowed development on Phi Phi Don to continue unchecked,"

he writes. "I'm all for boycotting travel to Phi Phi Don until the national park

comes to terms with greedy developers." In recent years, the park has been overrun by

group tours from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore. They hired jet skis and rode

glass-bottom boats to see bird-nesting sites at Phi Phi Leh. "PPI is trashed,"

says Noah Shepherd, a British environmental tourism consultant in Phuket. He cites lack of

water treatment, sewage and planning, and says the film-makers will likely leave the

island in better condition than before they arrived. "Besides," he adds,

"this isn't a sanctuary, and we're not talking endangered species here."

Backpackers aren't to blame, says Joe Cummings, who wrote Lonely

Planet's Thailand guide. He says industrial pollution, overfishing and a long history

of rampant logging, legal and illegal, have done the real damage to the environment.

Cummings' guidebook even warns tourists to steer clear of the Phi Phi islands. "The

park administrators have allowed development on Phi Phi Don to continue unchecked,"

he writes. "I'm all for boycotting travel to Phi Phi Don until the national park

comes to terms with greedy developers." In recent years, the park has been overrun by

group tours from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore. They hired jet skis and rode

glass-bottom boats to see bird-nesting sites at Phi Phi Leh. "PPI is trashed,"

says Noah Shepherd, a British environmental tourism consultant in Phuket. He cites lack of

water treatment, sewage and planning, and says the film-makers will likely leave the

island in better condition than before they arrived. "Besides," he adds,

"this isn't a sanctuary, and we're not talking endangered species here."

Still, controversy rages. As filming on the island finished and restoration began in early February, The Beach was hit by another storm. Shooting last week at a waterfall in Khao Yai National Park northeast of Bangkok brought a cascade of new charges. That the park would be closed, the waterfall dammed to increase flows and so on. "To be honest, the reaction has been shocking, and quite unnerving," says producer Andrew Macdonald. "There have been so many false and ridiculous accusations. Accusations of damaging the coral and using pesticides. Then, there have been accusations of bribery. This is outrageous, totally false."

Macdonald points out that all work on the island has been under the supervision of a Thai forestry worker and an environmentalist, not to mention a botanist brought from Britain to oversee replanting of the native species. Still, in hindsight, he concedes, "maybe things should have been done different." In fact, The Beach's damage-control has been disastrous. Movie-makers began by trying to gag all information about the film, closing the site, which fueled suspicion. When things went from bad to worse, the public-relations machine began rolling out releases, including love letters from Leo to Thailand. It was too little, too late. And when they responded to ecological concerns, it was with a statement from a reef-monitoring group that had to be corrected a half-dozen times over petty matters, like the titles of the people involved.

CONTROVERSY ASIDE, "The Beach" most certainly

will lure many more backpackers to Thailand, and Asia, for the same thrills Garland

parodies in his book. "That would worry me," he admits. "But it's all

speculation until the movie comes out. I don't see Leo fans jumping on planes and coming

to Thailand." But that is the hope of Thai officials, who are already looking far

beyond the estimated $13-million-plus in direct spending the film has injected into the

economy. "Movies have always played a major role in promoting destinations,"

says tourism chief Seree. "In spite of controversies regarding portrayal of facts or

fiction, movies create images that stay in people's minds."

CONTROVERSY ASIDE, "The Beach" most certainly

will lure many more backpackers to Thailand, and Asia, for the same thrills Garland

parodies in his book. "That would worry me," he admits. "But it's all

speculation until the movie comes out. I don't see Leo fans jumping on planes and coming

to Thailand." But that is the hope of Thai officials, who are already looking far

beyond the estimated $13-million-plus in direct spending the film has injected into the

economy. "Movies have always played a major role in promoting destinations,"

says tourism chief Seree. "In spite of controversies regarding portrayal of facts or

fiction, movies create images that stay in people's minds."

The Beach is already proving its drawing power. It lured the Japanese Leo followers, Maya, and countless more here, just like the paparazzi and me. We came for the hype. The buzz. Leo. Later, others will follow the plot-line of the book, of the movie. Looking for the ultimate beach. Maya is already home in Ko Samui, where she works as a healer. In the end she passed Leo's crystal to a minor member of the cast. "It was supposed to reach Him," she says. Shimomura is banging out her book, and the Thai students are busy updating their website. Leo will soon leave and move on to other projects, different fans, more hysteria.

At Maya Bay, crews are already putting things back the way they were, even replanting

the weeds. Islanders are debating what to do with a temporary dock and other improvements;

most want to keep them. Meanwhile, Thailand grapples with the role backpackers play in a

society that is so much more Westernized than most in Asia. When Lonely Planet's

Cummings was interviewed last week by the Nation newspaper, he was asked: "How do you

see the growth of the backpacker cult in the past years?" That's how it appears to

many Thais, this conga-line of rich, foreign kids pretending to be poor that snakes

through every year. But they don't build the backpacker hovels, or set the rules.

Ultimately, that is a matter for Thais.

At Maya Bay, crews are already putting things back the way they were, even replanting

the weeds. Islanders are debating what to do with a temporary dock and other improvements;

most want to keep them. Meanwhile, Thailand grapples with the role backpackers play in a

society that is so much more Westernized than most in Asia. When Lonely Planet's

Cummings was interviewed last week by the Nation newspaper, he was asked: "How do you

see the growth of the backpacker cult in the past years?" That's how it appears to

many Thais, this conga-line of rich, foreign kids pretending to be poor that snakes

through every year. But they don't build the backpacker hovels, or set the rules.

Ultimately, that is a matter for Thais.

Likewise the hoopla over the film. If laws were violated, that is up to a Thai judge to decide. And despite an environmental controversy that split ecology groups, many concede the battle may lead to refinement of vague areas of park law. As to the Phi Phi islands, peace and quiet won't return any time soon. Not with customers queuing up at the Rolling Stoned. And certainly not after the Christmas release of The Beach. By then, Garland's book will feature Leo's mug on the cover - bringing The Beach to the attention of millions more. Some of whose footprints, for better or worse, are bound to appear in Maya Bay.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who is based in Hong Kong, but who roams around Asia for a number of publications, such as Asiaweek, which ran this Inside Story in the February 19, 1999 edition.

Yo Leo fans! Please be patient. I posted this up quick, just for you, but you will have to wait for the photos. Check back later. In the meantime, for more inside views on The Beach, turn to exclusive interviews with producer Andrew Macdonald, who also made "Trainspotting," and another with Alex Garland, the hip young author who penned this gripping Utopian novel.

The photos on this page, (except for Garland, which is from the net) and much of the scanning for this site, are by David Paul Morris, an American photographer who often travels with Ron Gluckman. For other examples of Mr Morris' work, turn to the Urge to Merge, Melbourne Comedy, Hung Le, the Man Who Beat Beijing, Coober Pedy and China Beach. Or visit www.davidpaulmorris.com

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]