Tallest of them All

The race to build the biggest skyscraper moved from America to Asia then the Middle East in recent decades, but remained predictable. Each new high-rise tended to claim big-building bragging rights by tipping the previous champ by a few meters. Then, along came the Burj Dubai... Now, the sky is the only limit.

By Ron Gluckman/in Dubai, United Arab Emerates

BUILDING TALL HAS OBSESSED man ever since he crawled out of caves and began piling stone blocks one atop of another, always casting an eager eye toward the heavens. Early civilizations staked claims to greatness by erecting huge shrines, towers and pyramids, invariably equating importance, often immortality, with size.

Fast forward to the Modern Age, and size still means much, whether expressed by the iconic Eiffel Tower in Paris, or the clusters of skyscrapers shooting higher from Chicago to China. Tall, in terms of human achievement, it often seems, says it all.

Recent years have seen a steady

progression of spirited one-upmanship, with a new high-rise tower quickly

trumping the previous tallest. That has been the blueprint over the last dozen

years, since Malaysia’s Petronas Towers wrestled the title of tallest from

longtime champion America, spawning a global competition. Next to claim the

crown was Taiwan’s Taipei 101, but immediately new high-rise designs

circulated, with plans to go up a floor or two, whatever the cost, to gain

bragging rights to biggest building.

Recent years have seen a steady

progression of spirited one-upmanship, with a new high-rise tower quickly

trumping the previous tallest. That has been the blueprint over the last dozen

years, since Malaysia’s Petronas Towers wrestled the title of tallest from

longtime champion America, spawning a global competition. Next to claim the

crown was Taiwan’s Taipei 101, but immediately new high-rise designs

circulated, with plans to go up a floor or two, whatever the cost, to gain

bragging rights to biggest building.

That was the pattern of the recent past. But now, we arrive in an entirely new era – of mega-tall. So, take a deep breath, crane your neck, and marvel at the Burj Dubai.

Still soaring into the clouds with no end in sight, the Burj – “tower” in Arabic - doesn’t merely overshadow contenders, it takes a quantum leap to a new level. Take the four previous tallest towers – record holders for 75 years. The Burj already tops Taipei 101 by more than 100 meters, and is 150 meters higher than the Petronas and Sears towers. In March, the slender, shimmering Burj reached 160 floors; over 50 percent more than any before, including New York’s Empire State Building. By month’s end, the Burj breached the 630-metre mark, making it taller than anything manmade on Earth.

More astonishing still, nobody knows how tall this tower will grow.

“We’re not commenting, beyond saying it will be the biggest when done,” says Greg Sang, projects director for Emaar Properties, developer of the Burj. Eric Tomich, an architect with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), the American firm that designed the building, promises at least 700 meters. A metal spire on top could push the height well over 800 meters.

“The spire will be 40 or more

stories,” promises lead architect Adrian Smith, when we meet for dinner in

Dubai. Spires are common among tall buildings, which are judged for height

not only by occupied floors, but elements deemed integral to the overall

architecture. “The goal isn’t just size, it also creates a sense of

completion, a proper pinnacle. The reason is to create a strong and powerful

landmark, not just for Dubai, but also the entire Middle East.”

“The spire will be 40 or more

stories,” promises lead architect Adrian Smith, when we meet for dinner in

Dubai. Spires are common among tall buildings, which are judged for height

not only by occupied floors, but elements deemed integral to the overall

architecture. “The goal isn’t just size, it also creates a sense of

completion, a proper pinnacle. The reason is to create a strong and powerful

landmark, not just for Dubai, but also the entire Middle East.”

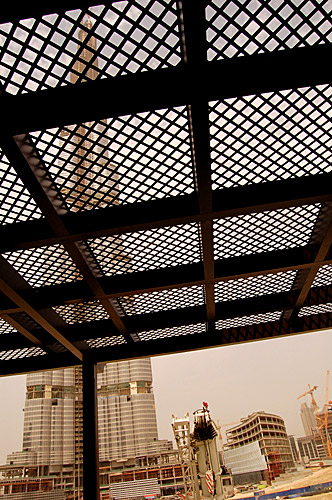

Then, he smiles as he shows me stunning views from the terrace of the restaurant, sited in a still-growing US$20 billion downtown project of hotels, offices and apartment blocks, all encircling a building so Space Age, it seems to have rocketed from another planet. “We said at the outset, this would either be a spectacular failure or success,” Smith says. Success already seems certain. Spectacular hardly sums it up.

In the process of becoming the tallest tower on the planet, the Burj shattered numerous records. Built with a concrete core, construction material was pumped to new heights. Because the building rose so fast, a special concrete had to be developed. “It had to be flexible enough to pump up through the hoses,” Tomich explains, “but fix fast.”

By pumping concrete as high as 600 meters – 150 meters more than ever before - Tomich says 5,000 or so workers on site were able to maintain an ambitious schedule, finishing a new floor about every three days.

When the building opens next year (in 2009) – the culmination of over 22 million man hours - it will feature the world’s fastest elevators, rising or dropping at 10 meters per second (over a metre per second quicker than the fastest, at Taipei 101). Over 50 lifts are arrayed to provide speedy access to different sections, with one express lift zooming direct to office levels at floor 124. That would be a record-breaking ride, except the Burj will also boast a service elevator that runs a total of 138 floors.

The views are out of this world

– quite literally. From the planet’s tallest observation deck on the 124th

floor, one can see 80 kilometers on a clear day, and the Earth’s curve.

“It’s cool,” Smith says. Already, Dubai marvels at the daily

changes in the building’s surreal shadow. “Now, that’s really cool,”

adds Smith.

The views are out of this world

– quite literally. From the planet’s tallest observation deck on the 124th

floor, one can see 80 kilometers on a clear day, and the Earth’s curve.

“It’s cool,” Smith says. Already, Dubai marvels at the daily

changes in the building’s surreal shadow. “Now, that’s really cool,”

adds Smith.

If he seems unaffected by such heights, credit his work at SOM, considered the world leader in tall buildings, responsible for many landmark American structures, including the tallest, Sears Tower, and design of the new Freedom Tower, at the site of the former World Trade Center in New York.

Smith, who recently left SOM to start his own firm, Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture, designed the Jin Mao Building in Shanghai, which was the China’s tallest tower, and third-highest in the world, when it opened.

Still, he cannot help gushing

about the Burj, like a proud parent. “It’s already had a huge impact on

Dubai,” he enthuses, then suggests favorite views, almost like sharing wallet

photos. “In early morning light, and early afternoon, it’s very powerful,

with the reflections.” The building surface is a specially-designed glass,

that mitigates the raging desert heat, which sends temperatures soaring over 40

degrees.

Still, he cannot help gushing

about the Burj, like a proud parent. “It’s already had a huge impact on

Dubai,” he enthuses, then suggests favorite views, almost like sharing wallet

photos. “In early morning light, and early afternoon, it’s very powerful,

with the reflections.” The building surface is a specially-designed glass,

that mitigates the raging desert heat, which sends temperatures soaring over 40

degrees.

Custom double glazing was used, Tomich explains, to deflect heat-radiating rays, but let in natural light. The exterior looks metallic, shimmering silver or bronze. Cladding is largely aluminum, with massive 1.5 by 3-meter panels manufactured on the ground, then hoisted by huge cranes and hung upon the exterior frame like curtains. The Burj will have 28,000 panels.

Everything was designed with the desert dust in mind. Horizontal surfaces were avoided. Even so, cleaning will be a task as big as the Burj itself. Cleaning machines will roam like miniature trains on mounted tracks, just another hip feature of the façade. Even running constantly, they will take six to eight weeks to clean the entire surface, which measures over 111,000 square meters – like 17 soccer pitches.

Over 31,000 metric tons of rebar was used to assemble the building, not including the massive foundation. Laid end to end, that would extend a quarter of the way around the world. Enough concrete was poured to build a sidewalk from Dubai all the way to Duba, Saudi Arabia, about 1,900 kilometers.

Smith’s design features a

clever array of clusters that provide a stepped shape; some say resembling wings

on this rocket-like building. Besides providing unique sections – for offices,

residences and the first-ever Armani hotel, all with their own entrances and

elevators – these clusters serve a variety of engineering feats. Most

important is helping to mitigate wind factors, which are critical to any tall

building.

Smith’s design features a

clever array of clusters that provide a stepped shape; some say resembling wings

on this rocket-like building. Besides providing unique sections – for offices,

residences and the first-ever Armani hotel, all with their own entrances and

elevators – these clusters serve a variety of engineering feats. Most

important is helping to mitigate wind factors, which are critical to any tall

building.

Tests and simulations revealed the exact locations where a heightened ledge would disrupt wind from reaching dangerous velocity while skimming over the Burj surface. Hence, there was no need to add the kind of massive stabilizing systems seen in many towers, like the pendulum in Taipei 101 or skybridge between the Petronas Towers. Once commonplace, Smith says such systems really underscore a lack of planning.

But such is the uncertainty of building big. Even Smith, among a handful of the most prominent designers of tall buildings, likens it to a space launch. “Every time we do a super-tall building, we increase our knowledge base by about 10 percent.” With the Burj, he found that the temperature at the top was several degrees cooler than at the base. “We could have used that to help cool the building,” he notes.

Such innovation is essential to what Smith says is the viability for future big projects – sustainability. As budgets increase, and energy costs skyrocket, buildings must wring benefits from the very design. Gordon Gill, Smith’s partner, comes from a background of energy efficiency and integrated urban planning. He talks of speeding up, rather than slowing wind forces, directing them in novel ways, to cool adjacent buildings at peak times, or generate power with fans on the building exterior. Such methods are part of their design for a China building that aims to be Energy Zero – generating all its energy. The pair are working on other buildings that will actually generate power rather than merely consume it.

“Buildings are just going to have to be more sustainable in the future,” Gill predicts. The Burj features a condensation system that draws water from the dry desert air. It is expected to yield 20-30 million gallons of water annually. “In an environment like Dubai, where drop counts, this is very important,” Smith notes.

Sustainability also registers in the way the Burj spreads value to surrounding development. Buildings like the Sears Tower stood alone, and had to recoup costs by leasing space. This cramps the bottom line, since towers have to taper at the top, yet still need space for lifts and other equipment, leaving less room to let.

The Burj is the anchor

of Emaar’s US$20 billion Downtown Burj Development, which will include

lots of apartments, hotels and entertainment venues, plus the world’s biggest

shopping center, Dubai Mall.

The Burj is the anchor

of Emaar’s US$20 billion Downtown Burj Development, which will include

lots of apartments, hotels and entertainment venues, plus the world’s biggest

shopping center, Dubai Mall.

Notes Sang: “Definitely, the tower increases the value of everything around it. We feel that Emaar can extract that value in surrounding areas.” Indeed, the Burj towers over hotel pools and dominates restaurant views, like a manmade Mt Everest.

This could not have happened in cramped cityscapes, like Chicago or Shanghai. “This is the kind of place where this development makes sense,” adds Tomich.

Sang adds that its simply the latest phase in a timeless race that has gone global. “Where tall buildings are built tends to follow places of economic growth,” he notes. “That was the United States in the 1920s. In the 1980s and 1990s, it was the time of the Asian tigers. Now, it’s the time of the Middle East.”

Indeed, the Burj restores honors for the highest structure to a region that hasn’t claimed it since the 1300s, when England’s Lincoln Cathedral eclipsed the Great Pyramid of Giza.

He reckons, despite the Burj’s huge lead over the competition, it won’t be tallest forever. Or even for long. Already, talk of taller towers circulates around the Gulf. Stories appeared in March saying that Saudi Prince al-Walid bin Talal, owner of London’s Savoy Hotel, planned a mile-high tower for near the Red Sea port of Jeddah.

The architects aren’t deterred in the slightest. Tomich says Emaar spent on quality to create a landmark for decades to come. “The Burj is already a great building, even if we stopped now,” adds Smith. “All that remains is to see whether it becomes magic.”

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has been based in Asia since 1991, roaming around the region, and beyond for various magazines, including Gulf Air, which ran this story in April 2008. Ron has written often about tall buildings, for such publications as Popular Science, Geo, Time, the Wall Street Journal, Silk Road and the Urban Land Institute.

Photo credits: Adrian Smith courtesy of Adrian Smith +

Gordon Gill Architecture

All other pictures by RON GLUCKMAN

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]