When Trouser People Ruled

Burma has been in a terrible slump, on and off the soccer pitch. A new book offers a funny kick. It traces the arrival of the sport a century ago, showcasing along the way not only Burma's modern misery but decades of headhunting and good old-fashioned colonial repression.

By Ron Gluckman /in the library

GOOD FORTUNE ALL TOO OFTEN PASSES BURMA, an utterly lovely land mired in misery and ruled by a succession of tyrants and military thugs. Hence, two events are reason for cheer, even if separated by a century or so.

One is the arrival of soccer (football to everyone except Americans). Never mind that Burmese rank among the world's worst players, they approach the game with admirable gusto. Likewise journalist Andrew Marshall, whose lively retelling of this tale in "Trouser People" (Viking) is the best book on Burma in ages.

This is not ordinary sports story. The focus is George Scott,

fascinating Victorian-era explorer, administrator, pioneering photographer and

all-around rogue who arrived in colonial Burma 130 years ago.

This is not ordinary sports story. The focus is George Scott,

fascinating Victorian-era explorer, administrator, pioneering photographer and

all-around rogue who arrived in colonial Burma 130 years ago.

He had scant Asian knowledge, none of British-ruled Burma, practically no governing skills and an unbridled independence that would later doom his diplomatic career - although he was knighted, surprisingly, later on. A skilled linguist and fearless traveler, Scott spent much of his life touring and snapping pictures of everyday Burmese, particularly remote tribes, many then enthusiastic head-hunters.

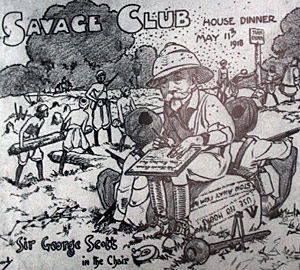

Scott was a talented photographer, and adept writer to boot. Oh yes, and something of a fanatical footballer, although this is really more an amusing footnote to the life of such an all-around swashbuckler.

Yet Marshall seizes upon football as one thread of his tale (sub-titled "The quest for the Victorian footballer who made Burma play the Empire's game"), sewing together descriptions of Scott's amazing adventures, mainly mined from original diaries, with Marshall's own experiences in Burma a century later.

Recreations of this kind, as any journalist chasing such a story well know, rely on two independent information trails. You need a solid story to follow, and an equally rich set of personal experiences of your own. The key to success is how they mesh.

Football is never the overriding device; more a clever attention-grabber, like the title, the Burmese name for the odd sarong-eschewing foreigner. Instead, Marshall paints a broad picture of Scott's larger-than-life existence in old Burma. His recreation seeks remaining traces of this Richard Burton-like character in the troubled land now known as Myanmar.

On these two levels, the book succeeds in varying measures. Scott's meandering life is riveting, his descriptions keep readers rapt: "Mandalay presented a series of violent contrasts, with jewel-studded temples and gilded monasteries standing side by side with wattled hovels penetrated by every wind that blew."

Ruling the then-independent city-state, Scott snaps, were "the

most inhuman in a long line of savage despots." Scott is no detached

colonial observer of the day. He takes particular pride in getting close to the

locals, learning their language, sharing their smokes and shacks, reveling in

their culture. "There was one Burmese phrase with no direct English

equivalent," he reports. "When a man was sitting in such a way that

his sarong was gaping wide open, how did you politely inform him? Well, now I

knew. You said cryptically, 'Excuse me sir, but I see your department store is

open even on weekends."

Ruling the then-independent city-state, Scott snaps, were "the

most inhuman in a long line of savage despots." Scott is no detached

colonial observer of the day. He takes particular pride in getting close to the

locals, learning their language, sharing their smokes and shacks, reveling in

their culture. "There was one Burmese phrase with no direct English

equivalent," he reports. "When a man was sitting in such a way that

his sarong was gaping wide open, how did you politely inform him? Well, now I

knew. You said cryptically, 'Excuse me sir, but I see your department store is

open even on weekends."

Marshall is no less a wit, and a canny observer, as he has demonstrated throughout his young career as freelance correspondent in far-flung places for Esquire, Arena and the South China Morning Post magazine. This debut (he also co-wrote "The Cult at the End of the World," about the Aum in Japan), is peppered with colorful detail, told with Marshall's trademark inventive twists of phrase. Yet the story slips most obviously in the places it really should be bound, by shared experience. There simply is too little intersection.

In the end, the story is not one, but two distinct tales, of Scott's early exploration and the author's more recent visits. The latter just don't match up, despite the author's inventive effort.

Hence, this description of a border crossing to Tachlilek: "I realized you never just go to Burma. Only tourists do that. Journalists, diplomats and aide workers always go into Burma, like you do into battle, the suggestion being, I suppose, that you might not come out again." Readers would hardly recognize the short jaunt across a bridge from Thailand that has been a popular day-trip with tourists for years.

Marshall also flounders at times in trying to convey the wide expanse

between lofty topics and the benign - both abounding in Burma. His blithe

reference to human rights statistics and quotes from fellow reporters is more

the mark of the uninformed scribe from overseas he'd normally ridicule than a

seasoned observer in Bangkok, such as the author. More irritating is his glib

sophomoric glee at describing an elephant enema and "ladyboys,"

sideline material that would better be saved for a Marshall magazine piece than

allowed to underscore the otherwise scholarly tone of a well-researched tale.

Marshall also flounders at times in trying to convey the wide expanse

between lofty topics and the benign - both abounding in Burma. His blithe

reference to human rights statistics and quotes from fellow reporters is more

the mark of the uninformed scribe from overseas he'd normally ridicule than a

seasoned observer in Bangkok, such as the author. More irritating is his glib

sophomoric glee at describing an elephant enema and "ladyboys,"

sideline material that would better be saved for a Marshall magazine piece than

allowed to underscore the otherwise scholarly tone of a well-researched tale.

Call these criticisms quibbles, because despite the flaws, Marshall has delivered that rare work - an authoritative historical account that is a riveting page-turner. Much of the credit belongs to Scott, a real find in the archives of Asian eccentrics. Yet it's Marshall's craft as both writer and reporter than makes this a World Cup-quality read.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who is based in Beijing, but who roams around Asia for a number of publications, such as the Asian Wall Street Journal, which published this piece in its Weekend edition, August 9-11, 2002.

All pictures from "Trouser

People" and credited: top and middle - British Library; bottom - Cambridge

University Library.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]