Divided by Death

President Joseph Estrada always pumped for the tough-guy parts, first as a film actor, and later as crime-busting politician — roles that took him all the way to the highest office in the Philippines. Yet, the hard-hitting president is having the fight of his life over the death penalty

By Ron Gluckman /Manila

A

YEAR INTO HIS TERM, PRESIDENT ESTRADA IS SQUIRMING on an unexpected hot seat over the issue. Unexpected, because the once-punchy president has always been cheered for his crusade against the kidnappers and murderers who plagued Filipino society a few years back.The public overwhelmingly supported the return of the death penalty at the end of 1993. Lawmakers and the courts have been enthusiastic. Nearly four dozen crimes in the Philippines, including possession of pot, can now be punished by execution — one of the broadest death codes in the free world. Justices have handed out death sentences at such a ferocious rate that, in only a few years, the Philippines has put 1,100 men and women on death row, second in number only to the United States among democratic nations. More people languish upon death row in the Philippines than anywhere else in Asia.

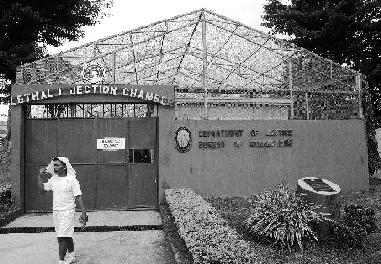

Yet, there has been nothing but trouble at the execution chamber at Muntinlupa, an hour

away from Manila.

Only a handful of convicts have been put to death since February, when the Philippines executed its first inmate in 23 years. Instead, Estrada has issued a series of last-minute reprieves, gaining an unwelcome reputation for wavering.

On June 25, only minutes after telling reporters that Eduardo Agbayani would be executed that day, the president bowed to an appeal from Bishop Teodoro Bacani. The president phoned from home to the execution chamber, but got a busy signal, then a fax tone. By the time an aide reached the presidential office hotline, Agbayani was dead.

There were no similar snags on July 8 when three men were executed for robbing a jeepney, a kind of local minibus, and killing an off-duty policeman who was on board. The trio claimed innocence to the end.

Human rights groups alleged considerable legal abuse, including torture of the accused and witnesses.

Such excesses are common, according to rights monitors in the country and abroad. Only the day before the execution, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of a new trial for another death row inmate. The court finally acknowledged the incapacity of Marlon Parazo, who is a deaf mute with the mental age of eight years. Despite repeated defense pleas, his disability was somehow overlooked through a series of earlier hearings.

Such occurrences have spawned new concerns about the death penalty process. Prior to the execution of rapist Leo Echegary in February, the Supreme Court, which automatically reviews all death sentences, had made final rulings on nearly 60 cases. About an equal number of death penalties were affirmed as commuted. In over 10 percent of the cases, the supreme court ruled for acquittal.

"This isn’t like a state with well-defined procedures, standards and safeguards," said attorney Jose Diokno, leader of the Free Legal Assistance Group, which handles most of the final death penalty appeals. "Here, it’s all the process of development," he added.

FLAG lacks the funds to get involved prior to final appeals. Instead, representation is largely handled by an over-burdened Public Attorney’s Office. PAO officials concede that attorneys have no special training in death cases, and the office lacks investigation abilities independent of the Department of Justice, which also oversees prosecution, the prisons and executions. Some death row inmates claim PAO attorneys advised them to plead guilty to get a lighter sentence, unaware that the charge carried a mandatory death sentence.

In the Philippines, the lowest courts impose the death penalty. Critics say this procedure spawned a "death rush" among justices eager to appease the public appetite for vengeance. Indeed, many prisoners went to jail in T-shirts emblazoned with the motto, "Guillotine Club." They were gifts from judges who ascended to the exclusive association by issuing a death decree.

Maximo Asuncion founded the club, but died before his edict on Echegary could be carried out. Ironically, Echegary wasn’t meant to be the first person to be put to death by Manila since 1976. The first in line was Fernando Galera. But at the last minute, after three years on Death Row, he was judged innocent and released.

"It’s really like a lottery in the Philippines," says Tim Parritt, a London-based Amnesty International researcher who studies the Philippines. Even a senior prison official at Muntinlupa confided: "There are many innocent people inside, I know that."

The risk of error is so pronounced that Asiaweek Magazine, a leading regional news weekly, recently printed a cover story that pondered: "Does Manila have the judicial maturity to mete out the ultimate penalty?"

This situation isn’t what the Philippines had in mind when it became one of the only nations in modern times to restore the death penalty after earlier bucking the regional trend by banning it.

Worldwide, capital punishment is on the decline, but it is entrenched in Asia, where even progressive countries like Japan, Taiwan, Thailand and South Korea retain it. Singapore is believed to be the world’s leader in per capita executions. Overall, 70-80 percent of the world’s executions occur in China, which puts to death over 1,000 people each year for crimes that include graft, corruption, embezzlement and drug trafficking.

Drugs offenses are capital crimes across Asia. Possession of as little as three-fourths of a kilogram of marijuana can be punishable by death in the Philippines. One Filipino farmer is currently on death row for growing seven pot plants. He feinted after the verdict was translated to him. A poor, rural resident, he didn't speak the language in which his trial was conducted.

The Philippines banned the death penalty for all crimes in its 1987 constitution, following the overthrow of the Marcos regime, which had put to death many political opponents. However, an outbreak of kidnappings, killings and coups at the end of the 1980s prompted lawmakers to restore capital punishment.

Critics point out that crime rates for murders and kidnappings have actually declined steadily since 1990, years before the penalty was reinstated.

President Estrada has repeatedly promised to excuse crimes motivated by poverty, but that is one of the few common threads on death row. A survey of 425 death row inmates in 1998 showed that the majority earned under $6 per day. Three-fourths were farmers, agriculture workers or common laborers.

"Death Row is a home for the poor," said Father Silvino "Jun" Borres, director of the Philippines Jesuit Prison Service.

About 53 percent of the 1,000 death row inmates are rapists. This, too, has become a matter of controversy. In a recent case, the Supreme Court overturned a verdict of death for a rapist, bringing cries of protests from the young victim. She was due to receive 100,000 pesos ($2,700) in compensation. By quashing the death sentence, the judges automatically slashed the figure in half.

Rape convictions in the Philippines do not require corroboration or supporting evidence. Generally, the word of the victim is enough. The rationale is that the stigma of rape is so severe, that no Filipina would falsely claim to be raped. Yet, even some women’s groups are questioning that logic as rape reports continue to soar, defying regional trends.

Since the executions on July 8, there has

been renewed opposition to the death penalty, with a group of lawmakers calling for a

total review.

Since the executions on July 8, there has

been renewed opposition to the death penalty, with a group of lawmakers calling for a

total review.

The church, a huge power in this Christian nation, has joined the call for a moratorium.

And even public sentiment seems to be changing. No reliable surveys have been done, but Jessica Soto, director of Amnesty International Philipinas, estimates that as many as 90 percent of the public supported the restoration of the death penalty. She thinks that support has now dwindled to about two-thirds.

That figure is about the level gauged by Adrian Sison, an attorney who conducted a phone survey on his daily radio show, "Broadcasters Bureau."

"People really have the notion that it’s a deterrent," said Sison, who said that belief is fading. "You can go back in time. When they hung pickpockets publicly in England, pickpockets worked the crowd."

Indeed, studies worldwide have failed to match the death penalty with drops in crime. The United States, which has executed more than 500 prisoners since 1977, has thousands on death row and some of the world’s highest murder rates. These statistics have prompted even staunch law enforcement personnel to speak out against the death penalty.

Much the same situation is beginning to happen in the Philippines where the heads of both men’s and women’s prisons oppose executions.

"We’re supposed to be in the business of rehabilitation," explained Rachel Ruelo, superintendent of the Women’s Correctional Institute, where 19 women await execution. "How can I rehabilitate a dead person?"

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who is based in Hong Kong, but who roams widely around Asia for a number of publications, including Time, People, the Wall Street Journal, and Asiaweek, which ran a cover story on this subject by Ron Gluckman in its July 23, 1999 edition. To see that story, click upon .Inside Death Row. This piece ran upon MSNBC. Both articles feature pictures by Manila photographer Edwin Tuyay

In late June 2006, Philippines President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo signed a law abolishing the death penalty, sparing the lives on an estimated 1200 people on Death Row.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]