Hong Kong of the Desert?

Oil riches flooded the UAE with lots of silly ideas and excesses, but one Emirate invested heavily in hotels, industry and infrastructure, aiming to turn Dubai into the trading center of the Middle East.

By Ron Gluckman/Dubai, UAE

THE DRY DESERTS OF THE MIDDLE EAST have induced intensely personal delusions. The pioneers who gazed upon the barren plains of Palestine a half century ago saw farmland. Irrigation turned Israel into the world's leading exporter of citrus fruit.

Around the Gulf, drab cities now sparkle like Las Vegas casinos. All it took was a sprinkling of oil, and the sand sprouted high rises, hotels and beach resorts.

However, among desert dreamers, none has shown more foresight than Sheikh Rashid Bin Saeed Al Maktoum, the late ruler of Dubai. Even as oil gushed from the ground, Maktoum recalled the parched dunes of Dubai and dreaded the day that the desert would reclaim his people.

"My grandfather rode a camel, my father rode a camel, I drive a

Mercedes, my son drives a Land Rover, his son will drive a Land Rover, but his

son will ride a camel," the Sheikh was fond of saying.

"My grandfather rode a camel, my father rode a camel, I drive a

Mercedes, my son drives a Land Rover, his son will drive a Land Rover, but his

son will ride a camel," the Sheikh was fond of saying.

However, Maktoum ensured such proverbs won't be prophecies in Dubai.

In his accruing oil wealth, the Sheikh saw salvation. While other Gulf leaders invested in mansions and munitions, Maktoum's black gold bought infrastructure, offices and modern communications. Many observers thought old Maktoum was suffering from sun stroke, when, in the middle of Dubai's flat desert, he erected the tallest building in the Middle East. Now, Sheikh Maktoum's World Trade Center is no longer surrounded by sand, but by bustling conference halls and hotels.

Detractors snickered when he said he would turn Dubai into a Hong Kong of the Middle East. Nobody is laughing anymore.

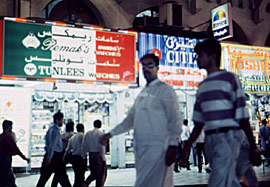

Nowadays, high rises provide a glittering backdrop of leaded glass as ships unload goods at Dubai Creek from every part of the globe. Claiming to be the strategic shipping center for a market of one billion consumers, Dubai maintained it's edge even before the local dry-docks reached capacity. Maktoum commissioned construction of the world's largest man-made harbor, at Jebel Ali, a new free trade zone.

As a result, while the western world is gripped by recession, Dubai is

booming. Economic activity is everywhere. The city center is a construction zone

with international hotel chains competing for sites. Hyatt, Hilton, Ramada and

Sheraton are already represented; Marriot and Holiday Inn are on the way.

As a result, while the western world is gripped by recession, Dubai is

booming. Economic activity is everywhere. The city center is a construction zone

with international hotel chains competing for sites. Hyatt, Hilton, Ramada and

Sheraton are already represented; Marriot and Holiday Inn are on the way.

Golf courses are sprouting in the suburbs, while resorts dot the coastline. And Dubai International Airport, second busiest in the world after Tokyo's Narita, is awash in cash from the world's largest duty free shopping center.

"People call this the Hong Kong of the Middle East," says Lawrence Mills, a lifelong Hong Kong civil servant who is now chief executive of the Dubai Commerce and Tourism Promotion Board. "But that's really limiting. I like to think of Hong Kong as the Dubai of Asia."

Such sentiments are dismissed as snide optimism by outsiders, but here in Dubai, the wealth of statistics is staggering.

Natives in the seven-state confederation of the United Arab Emirates earn an average of nearly US$30,000, among the world's highest annual income. Dubai is second on the list, after Abu Dhabi, where annual income was estimated by one bank to average a staggering US$128,000.

Oil is the spoil, but what happens when it's gone? Abu Dhabi may not have to answer for 100 years, but Dubai reserves will likely be exhausted within 10-20 years.

Sheikh Maktoum could see the future. Rather than condemn his descendants to camel-back, he nurtured the most diversified and thriving economy in the Middle East.

The comparisons to Hong Kong are striking. High rises, modern roadways,

tunnels underneath the harbor, and exceptional services distinguish the twin

port cities. Each thrived under British protection dating back to the 1800s.

The comparisons to Hong Kong are striking. High rises, modern roadways,

tunnels underneath the harbor, and exceptional services distinguish the twin

port cities. Each thrived under British protection dating back to the 1800s.

Both are famed for duty-free trade in countless consumer goods, from electronics and house wares, to jewelry and textiles. Most important, each outpost offers access to enormous surrounding markets.

"Dubai is a gateway," agrees Mills. "In that regard, Hong Kong and Dubai have much in common, as gateways to a hinterland with a lot of consumers. They have to be strategically neutral, politically neutral. The dollar is the direction both follow."

Omar A. Deesi, foreign relations advisor to the Dubai Chamber of Commerce and Industry, sees vital differences. "The similarity of Hong Kong and Dubai is that both are trading centers in their areas. The difference is that Hong Kong will be affected by its complete attachment to one country; China. Dubai has no such attachments."

However, a case can be made to the contrary. Dubai's rapid emergence as a trading center can be seen to parallel the isolation of one of its major patrons; Iran. Just as Hong Kong is the door to difficult trade with China, Dubai offers access to ostracized Iran.

While Japan, Britain, the United States and Germany were the biggest exporting partners to Dubai in 1990, averaging over 10 percent gains in export value over 1989, nearly 20 percent of the US$8.4 billion in goods shipped to Dubai were re-exported. And nearly US$2 billion went to Iran, which has dominated Dubai's trade list for years. Re-exports to Iran have grown by 20 percent or more every year since 1989.

"Dubai has been called the City of Merchants for good reason," Deesi says. "Dubai was a trading center long before oil came along. Now, Dubai has four ports, 110 berths and the largest dry docks in the world. We have the facilities to accommodate a one-million ton crude oil tanker, which doesn't even exist. Dubai is ready for the future."

"If and when the oil is exhausted, the strategic location of Dubai will remain unaltered. The commercial activity will only grow."

Deesi says the volume of trade in Dubai has multiplied by 150 times over the past 20 years. Dubai itself is a major consumer, with imports increasing 20.3 percent in 1991 to top US$10 billion. This is a sizable sum for a state of half a million people.

"Dubai per capita imports are now the highest in the world," boasts Deesi.

While oil wealth offsets worries about balance of trade, Dubai is looking to

diversify its income. One area of potential expansion is

tourism, with Dubai

showing interest in liberalizing stern measures that still require all visitors

besides British nationals and Gulf residents to obtain sponsored visas.

While oil wealth offsets worries about balance of trade, Dubai is looking to

diversify its income. One area of potential expansion is

tourism, with Dubai

showing interest in liberalizing stern measures that still require all visitors

besides British nationals and Gulf residents to obtain sponsored visas.

The Dubai Commerce and Tourism Promotion Board was created by government decree in 1989. There are now seven offices worldwide, including Europe, the US and Hong Kong.

Yet the Arab Emirate remains a family-run kingdom. Sheikh Maktoum Bin Rashid Al Maktoum succeeded the late Sheikh Maktoum, his father, as UAE vice-president and ruler of Dubai. Three other sons serve as Minister of Defense, Minister of Finance and Industry, and Commander of the Military. The late Sheikh Maktoum's brother, Sheikh Ahmed bin Saeed Al Maktoum, heads civil aviation, is chairman of Emirates Airlines, and chairs the Dubai Commerce and Tourism Promotion Board.

And while Hong Kong leaders battle Beijing over the airport, Dubai is busy building its own Disneyland, an Arab theme park with Magic Carpet rides and other ethnic amusement. "Dubai and Hong Kong will be taking tourists and investors on different rides within a few years," jokes Mills.

And Dubai's Disneyland is bound to be more comfortable than camels.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter based in Hong Kong, who visited Dubai in 1992 for a variety of stories including this business story, which ran in Asia, Inc.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]