Maverick's last stand

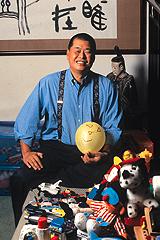

Hong Kong entrepreneur Jimmy Lai has successfully stood down Beijing, muscled his way into Hong Kong's tight-knit media market and challenged the local oligarchy. But now, he's facing the fight of his life as he tries to redefine the way people in Hong Kong do business. His foray in e-commerce could sink his Apple empire.

By Ron Gluckman and Robin Ajello/Hong Kong

H

ONG KONG MAVERICK JIMMY LAI IS BLEEDING MONEY. By his account, as much as $10 million a month. The hemorrhage is the consequence of the June launch of adMart, Lai's Internet-based grocery and electronics home-delivery service. The buzz is that Hong Kong's seemingly invincible entrepreneur may finally have taken on more than he can handle, mounting what many believe is a crazy crusade against a business establishment used to printing money without interference from anyone. Not from the government. Certainly not from an upstart who refuses to play by the rules. Then again, we're not talking about just any rebel. This is Jimmy Lai Chee-ying, a grade-school dropout who repeatedly has stumbled to rise again. Flamboyant,

outspoken and irreverent, the chunky textile trader turned media baron has

displayed a mostly golden touch since the 1980s when he founded Giordano, the

clothing chain that became an Asia-wide brand. Lai went on to challenge Hong

Kong's powerful media moguls in 1995 with his publishing phenomenon, Apple Daily

newspaper. Along the way he has riled potentates; after the Tiananmen crackdown,

he sold cheap Giordano T-shirts adorned with photos of the student leaders;

later he memorably called former Chinese premier Li Peng "the son of a

turtle's egg with zero IQ."

Flamboyant,

outspoken and irreverent, the chunky textile trader turned media baron has

displayed a mostly golden touch since the 1980s when he founded Giordano, the

clothing chain that became an Asia-wide brand. Lai went on to challenge Hong

Kong's powerful media moguls in 1995 with his publishing phenomenon, Apple Daily

newspaper. Along the way he has riled potentates; after the Tiananmen crackdown,

he sold cheap Giordano T-shirts adorned with photos of the student leaders;

later he memorably called former Chinese premier Li Peng "the son of a

turtle's egg with zero IQ."

At times, Lai has been his own worst enemy. His irreverence forced him to divest Giordano after Beijing refused to allow its stores on the mainland (Lai made some $280 million from the sale). For several years he tried fruitlessly to get a berth on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange but was thwarted - by Beijing-backed rivals, he says - until mid-October when he succeeded in winning a backdoor listing. Lai has earned the enmity and lawsuits of many powerful people with his publications' coverage. And in truth, he is more marketer than innovator. Giordano, for example, was from the start a poor man's imitation of Gap, the American clothing retailer. (And Lai copied the Giordano name from a New York pizzeria.) Apple Daily resembles the most outrageous of British tabloids. And even adMart looks a lot like similar services in California.

Yet Lai's image is of a maverick and it plays well in a city where old-money billionaires and banal Canto-pop singers pass for celebrities. In such company, Lai stands apart: rough, independent and fearless, a man determined to do business his own way. Now 51, Lai has matured. But his enthusiasm remains youthful. After all, he is wading into an arena that, for the most part, is a young person's game - e-commerce, to date a notoriously unpredictable and unprofitable business.

If Lai succeeds with adMart, he may manage to do something far more remarkable than merely make a profit or pioneer e-commerce in Asia. With a lot of luck (and money), he may also help change the way Hong Kong does business, forcing cleansing competition on the high-margin cartels and oligopolies that make a mockery of the city's much-vaunted laissez-faire business model.

Every time Lai tackles a new opponent or strategy, skeptics predict his demise. They are doing it again with adMart. Maybe they're right this time. Then again, maybe they're not.

Make no mistake. Jimmy Lai is deeply aware of the fix he is in. "I'm in deep shit," he confides. "Maybe it's a conspiracy. But not in the sense that it's secret. It's not. They're out to crush me." They, in this case, are the mostly self-made overlords of the business establishment. Lai adds: "It is like I'm trespassing. In Hong Kong, you just don't do that. I guess that's why this feels like a personal vendetta."

Until now, Lai has been reluctant to publicly name names. But one individual in particular has long been the perceived antagonist in an escalating war of attrition against adMart. Lai alleges that man is Li Ka-shing, chief of the Cheung Kong and Hutchison Whampoa groups. "You can call Li names; he does nothing," says a prominent media person. "But you put your finger in his pocket and he'll crush you. Jimmy is just in Li's territory, and Li will crush him."

Lai's adMart is no more than a little finger poking into Li's empire. His Hutchison owns huge retailers with which Lai's upstart is directly competing. Among them: Park'n Shop, a grocery chain with 183 stores in Hong Kong, and Fortress, a chain that sells appliances from televisions and compact disc players to toaster ovens and space heaters. Not that Hutchison is the only corporation with an interest in seeing adMart fail. Dairy Farm, owned by Jardine Matheson, the venerable British hong, is also in direct competition, specifically with its 228 Wellcome supermarkets.

Lai claims that both Dairy Farm and Hutchison are waging war on adMart by ordering their subsidiaries to pull advertisements from his Apple Daily newspaper and Next magazine. "This is really dirty pool," says an analyst, who requested anonymity. But, he adds: "Jimmy started it by using his newspaper to push adMart. Don't forget, it's only adMart in English. The Chinese call it Apple Delivery. So the borders were blurred from the beginning."

Moreover, while Park'n Shop and Wellcome ads have indeed disappeared from Lai publications, the real impact of this on his business has been exaggerated. Neither Park'n Shop nor Wellcome were big Apple Daily advertisers in the first place; they favored the Oriental Daily News with their business. Representatives from both chains deny the disappearance of their ads from Apple has anything to do with adMart. But they acknowledge doubling their advertising budgets to counter Lai's online retailer. Between them, the two chains are spending about $1 million a week - that's some 60 pages of ads - in Oriental Daily News, Apple's fiercest rival.

More damaging to Lai by far has been the exodus of lucrative property ads from the pages of Next and Apple. Apple advertising manager Peter Kuo claims eight property developers, including industry giants Henderson, Sun Hung Kai and Sino Land, pulled their ads for three months, starting in August. "It really seems like they made this agreement to hold out advertising from us for three months," he says. Now, however, they are coming back.

"Most of these people are not even friends of this powerful man," says Kuo. "That's why we think he's orchestrating this whole thing through intermediaries." Either way, Kuo reckons the mysterious exodus cost Next Media up to $2 million a month, 75% of it at Apple. Kuo figures the media group lost a further 1% to 2% of its revenues when subsidiaries of Swire, another well-diversified conglomerate, also pulled ads. Swire isn't involved in the supermarket war, but it bottles Coke and does not sell it to adMart.

For the most part, the big squeeze seems to be going on behind the scenes. This, says Lai, is where the cartels come into play. Analysts familiar with how things work in Hong Kong speculate that Lai is probably being blacklisted by distributors of food and electronics. No proof of this exists but there are questionable circumstances. Why, for example, did adMart have so much difficulty convincing Japanese electronics suppliers to sell it appliances? Why are the grocery and electronics sectors most affected? "We don't have any problems with office supplies and mobile phones," Lai says. "There is no cartel in those areas."

There is nothing illegal about the way biggies like Hutchison and Jardine operate in Hong Kong. They have been doing so unmolested virtually since the city was founded. Both groups are classic vertically integrated conglomerates with a presence through the entire grocery supply chain. Jardine's Dairy Farm, which dominates the market in milk products, owns Mannings, a chain of drug and household goods stores, and operates local 7-Eleven stores. Add in its Wellcome supermarkets and this is a formidable group with commensurate powers of persuasion.

For its part, Li's A.S. Watson and Co. division includes an enormous operation centered around three of Hong Kong's largest retail chains: Watson's drug and variety stores, Fortress electronics and household appliance stores and the market-leading Park'n Shop supermarkets. This powerful chain not only can dictate terms to distributors, but itself controls crucial product lines. Its beverage division is Hong Kong's largest water bottler and a major producer of juices and soft drinks. It also holds licenses to bottle such international brands as Sunkist, Pepsi and 7-Up, leaving little toehold for potential challengers.

For

a guy losing $10 million a month and engaged in the battle of his life, Jimmy

Lai manifests remarkable equanimity. Perhaps it can be attributed to his daily

qi gong sessions at the Kowloon Cricket Club. Maybe it is because he found God

in 1997, when he became a Catholic at the urging of his second wife Teresa.

Certainly, he is starting to mellow, and his workday is a variation on the

frenetic theme set by most Hong Kongers.

For

a guy losing $10 million a month and engaged in the battle of his life, Jimmy

Lai manifests remarkable equanimity. Perhaps it can be attributed to his daily

qi gong sessions at the Kowloon Cricket Club. Maybe it is because he found God

in 1997, when he became a Catholic at the urging of his second wife Teresa.

Certainly, he is starting to mellow, and his workday is a variation on the

frenetic theme set by most Hong Kongers.

Lai rises at 5 a.m., reads the bible for about an hour, then heads across the street to do his exercises. By 8 a.m. he is at the Apple offices in Tseung Kwan O, an industrial district in Kowloon, where he stays until 6 p.m. He is in bed by 9:30 or 10. Unlike most of Hong Kong's business glitterati, Lai rarely ventures out at night. He is noticeably absent from the charity balls and other celebrity functions that represent success in a city of public strivers. As a result, his picture rarely makes the gossip or glamour pages. A family man, Lai takes the time to vacation with his wife and kids four times a year. "I drop everything and go," he says. And dad leaves his work behind. "He eats, sleeps and looks," says his wife. "That's about all."

Clearly vexed by his stunted education, Lai spends much of his waking hours reading - philosophy, politics, biographies. Never novels. "Ilike serious books." And he relishes intelligent conversation with good company, often hosting friends on his yacht, Free China. On a recent outing, the guests included an elderly priest originally from rural China but now living in Chicago, as well as a British missionary born in - and banished from - Szechuan province.

Even with journalists on board, not once does Lai push his business agenda - at least not overtly. Rather, he mostly listens, interjecting the occasional joke. When talk of the precarious position of Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji recalls the financial jitters that accompanied rumors of Deng Xiaoping's death years ago, Lai looses a barb at Hong Kong's chief executive. "If Tung Chee-hwa dies," he chortles, "the stock market will take off."

Lai's exuberance is disarming. He bounces around the boat like an oversized kid at summer camp. At one point, he tries to rouse interest in a swim. Finding no takers, he slips out of his baggy, green trousers and gray T-shirt, and, stripped to yellow-striped trunks, flings himself overboard. Clambering to the second deck, his large belly hanging shamelessly over his bathing suit, he plunges back in. Moments later, he is fast asleep below.

Plainly, Lai is no ordinary mogul. Like many Hong Kong tycoons, his is a classic rags-to-riches tale - he fled solo by boat from Guangzhou to Hong Kong at the age of 12 in 1960 and toiled in factories, as did many of his contemporaries. Yet it's hard to find the ostentation typical of the self-made man. Lai usually rides around in a silver Lexus with black interior; it's a nice car, sure, but it's no Rolls-Royce. He runs his burgeoning empire from a simple office off the Apple Daily newsroom. Until recently, he didn't even have walls or a door, just a cubicle like any reporter or copy boy. "We made him put up some walls," quips a senior member of the Next staff. "Jimmy snores so loud, we couldn't get any work done." Lai retorts that the office is useful for meetings, then adds wryly: "Also, I can nap and nobody knows."

At his large, comfortable but understated apartment, the furniture is simple, the couch covers old and covered in red, blue and yellow crayon marks, courtesy of his youngest children, Sebastian, 5, and Claire, 3. Lai used to live in a large detached house, but Teresa insisted that they move to a more secure apartment complex after thieves invaded their home in 1995, whacked Lai over the head with a spanner and stole a small sum of cash and $258,000 worth of jewelry. A molotov cocktail had been lobbed into their front yard two years earlier. Teresa, fearful of potential kidnappers, is fiercely protective of their children.

Lai's 34-year-old wife has clearly been a major influence. They met in 1989. Lai was in the news because of his Tiananmen activism, and Teresa, an intern reporter visiting Hong Kong on a break from university in France, was interviewing him for Hong Kong's South China Morning Post. "It was love at first sight," says Lai, who at the time was despondent because his first wife Judy, the mother of his three oldest children, had left him for another man. Hong Kong-born Teresa was a devoted francophile, and before long, Lai was besotted with all things French. He followed Teresa to Paris. They wed in 1991. Lai describes his wife as his only real confidant. "When Ihave good news," he says, "Itell her."

In fact, Lai is self-reliant and hesitates to delegate. "One of his strengths is his drive, his energy," says one employee. "But as a manager, his weakness is an inability to see that teams are made up of individuals with different skills and different ways of doing things." Others say he is demanding, erratic and impulsive. Nonetheless, veteran colleagues say Lai has reined in many of his excesses. "Jimmy has mellowed a lot," says Next publisher Yeung Wai-hong. "The most obvious example is in meetings - the amount of profanity used to be overpowering. Now, he hardly ever swears." Yeung says Lai is also more disciplined; he attributes this to Teresa and Lai's conversion to Catholicism.

In truth, Lai is not especially interested in the fine points of his businesses; he is easily bored and constantly searching for new heights to conquer. Lai acknowledges that he likes to "grope around in the dark." Challenge is what gets him out of bed in the morning. And despite his renegade image, Jimmy Lai clearly relishes playing in the big leagues. "He likes to play this small guy standing up to giants," says broadcaster Albert Cheng. "He tackles the big guys because he wants to be one himself.

The older, wiser Jimmy Lai was much in evidence on Oct. 21, when he held a press conference to announce, at long last, his much-delayed stock exchange listing. Arriving right on schedule in a classy gray suit over his trademark suspenders, Lai took every question, answering with little emotion, apart from a quip or two. No off-color jokes, no insults aimed at Chinese leaders.

Lai is clearly relieved to put the listing behind him. His previous attempt ended in 1997 when Sun Hung Kai International pulled out of another deal to underwrite one. In the end, Lai bought Paramount Publishing Group, a public company that prints Apple Daily, injected a magazine and website valued at $43.5 million and issued new shares in return. When talks with Paramount grew serious earlier this year, the stock was trading at HK$0.15 a share. Lai paid a premium of HK$0.20 per share; the stock soared to HK$1.80 and has since settled back to about HK$1.10. "We didn't go public because we needed money," Lai says, but concedes: "It gives me the opportunity to do something big." Indeed, the listing opens up a line to funds for a maverick who might have a hard time finding partners because of his checkered past and his risky present.

Lai calls adMart Hong Kong's first all-out foray into e-commerce. Critics have not been quite so complimentary. One dubbed the odd collection of foodstuffs and electronics, ordered over the Internet or by fax and delivered by van, a "Pricemart-pizza." Though the concept, the smart logo and the brightly colored vans got off to a quick start, the business was overwhelmed by the initial demand and the website crashed. Orders had to be taken by phone, and delivery delays ensued. It was an inauspicious start for an Internet play.

Later, with distribution channels allegedly choked off by its competitors, adMart was accused of delivering counterfeit goods, including Mouton Cadet wine. The company quickly acknowledged the charges and apologized, even as rival grocers gleefully posted gloating ads offering to sell the real thing at cut-rate prices. Since those early hiccups, adMart's service has improved, and the website, in Chinese and English, is fast and efficient. Yet skeptics continue to argue that adMart is ill-suited to densely packed Hong Kong, where a Wellcome, Park'n Shop or wet market is never far away. In fact, adMart is based on San Francisco's Webvan. Lai's critics say such services work in the U.S. because consumers have the storage space to shop in bulk. The truth is that, as in all Internet ventures, no one can accurately predict the future. Hence, many analysts are loath to give adMart the thumbs-up or thumbs-down.

Perhaps the strongest indication that Lai is on to something is the cutthroat response to the launch, and the fact that prices are coming down in grocery stores around Hong Kong. Besides, adMart is merely in the initial stage. "Groceries," says Lai, "are just a thing to help build the network. Our intention is to take services into people's homes so they can taste the convenience. Later, we'll sell other things." Besides food and electronics, adMart currently offers home and office furniture as well as computers. The target audience is fairly downmarket; one could describe adMart as the Internet five-and-dime of the future.

In December, Lai launches adMart Travel - an online plane ticket service. So far, he says, "we've had no adverse reaction from the travel industry." He also hopes to set up a distribution agreement with Wal-Mart, though the U.S. retailing behemoth has announced no such plans. And if adMart succeeds, Lai will start to spin off such businesses as the travel component. He will likely continue experimenting until he finds the right mix of online services. Eventually he hopes to become a regional e-commerce player.

In the meantime, he is resigned to the continuing gout of red ink. Lai doesn't expect to make money for at least two years. Can he sustain the losses? Colleagues fret that adMart could sink the entire Apple empire, but Lai says: "This won't put me out of business or bankrupt me. I'd pull the plug before that happened. Ijust don't think I'll have to." While Lai is a recent convert to e-commerce, his colleagues say he really gets it. "He knows we need to create need, not just put something on the Net, but to create something new," says one. "That's how it was with all his businesses, whether Giordano or Apple, always something new."

Plenty of smart people predicted Lai's trashy daily newspaper would never succeed against the entrenched players. It prospered, transformed Hong Kong's publishing landscape and prompted his rivals to launch their own versions. Now he is taking on a whole new set of even more powerful people - in fact an entire system for doing business. The stakes are higher than ever, but then that's how Jimmy Lai likes it.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who is based in Hong Kong, but who roams around Asia for a number of publications, such as Asiaweek, which ran this as a cover piece in November 1999. Robin Ajello is Gluckman's editor at Asiaweek.

The pictures are courtesy of Ira Chaplain

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]