Twelve Hours to the Taj

With only a day to spare in Delhi, the intrepid travel writer eschews a few laps around the pool, heading instead to the nearest world wonder, dodging elephants and mating rituals but finding magic on the way

By Ron Gluckman/New Delhi

T

RUMPETS BLARED, DRUMS THUNDERED. And the elephants danced a jig. The music was frenzied, but mysteriously focused as it slowly built into a steady, rhythmic dirge. The sun soared high in the sky, and sweat drenched the natty uniforms of the performers, dripping from golden fringes and armlets, until the dapper red and white outfits stuck to skin like wet cement. The players paid no notice, in fact, they even picked up the pace. The music was mad, not like music at all, but a beguiling tropical chant of trumpets

and trombones, driven by bells and the incessant pounding of wood on wood, wood upon skin.

The ground itself seemed to heave with every beat. Maybe it wasn't the sound so much as

the relentless heat, or maybe the shaking was due to the elephants, which were bouncing in

place like chunky ballerinas in a surreal, slow-motion ballet.

The music was mad, not like music at all, but a beguiling tropical chant of trumpets

and trombones, driven by bells and the incessant pounding of wood on wood, wood upon skin.

The ground itself seemed to heave with every beat. Maybe it wasn't the sound so much as

the relentless heat, or maybe the shaking was due to the elephants, which were bouncing in

place like chunky ballerinas in a surreal, slow-motion ballet.

Or maybe it was the mob, throbbing with excitement and expectation. More than a hundred people pushed into the square facing the entrance to the ancient city of Fatehpur Sikri. They swarmed the bottom of steep stone steps, which led up to a magnificently colonnaded arch that looked positively Roman in design. But down below, at the base of the steps, the scene was Indian in every way.

So many people were present, pushing, pulling and shouting, that the square seemed certain to explode. Not that there was anything violent or threatening about the crowd, except for the herky-jerky motions of its dance. This seemed primal and chaotic at first glance, but then a symmetry became apparent. The sound was like a spiritual thread woven through the crowd, knitting together hundreds of arms, legs and necks, so that when the drums snapped, so did joints. And when the horns blared, every head in the square moved as if choreographed with concert hall precision.

The musicians felt the mumbo, this incredible hot, sticky muse surging across the square. As the drums picked up the beat, or tala, as it is known in India, the horns started spinning an even faster raga, trumpets and trombones flaring in tandem. The mob moved faster and faster, screaming in the sun. The carnival of sound and celebration moved to crescendo.

Then, magically, like a happy ending for a saffron fairytale, the bride appeared, seated upon a white pony. She was covered in a veil from head to waist, woven with fine silk threads and flowers, thousands of bright crimson blooms. Across the square, frantic hands pushed the groom through the throngs. He was dressed all in white. His face was euphoric, and slowly he began to shake, hips and shoulders vibrating to his matrimonial raga. The crowd erupted in cheers, the trumpets wailed even louder, and the wedding festival seemed to switch to an even higher gear.

"Here, for your health," shouted a voice, almost into my ear. Spinning around, I saw an old Indian man, face partially painted, lips spun into the biggest smile imaginable. He pushed forward a gourd. Inside was a greenish-brown liquid. It smelled sickly-sweet, like the mad mob in this mid-day heat. But, as he pushed it into my face, he was beaming, eyes extolling me to surrender to the spell. I did. I drank it down, swallowing this odd elixir, this essence of India.

Only later, after writhing with the wedding jubilee for what seemed like hours, before escaping in my rented Tata sedan, was there time for reflection. What potion had I consumed? What was I doing in the square? How had a the day's excursion from New Delhi taken me so far afield, into this living fantasy?

It had all seemed so succinct at the start. My directive was clear and simple. Returning from another assignment in the Himalayas, I had arrived at the hotel in New Delhi and checked in with my editor. There were no flights out until the following night, so that left a day to kill in Delhi. "Take a day off," my editor had advised. "After all, what can you get done in a day. Especially in India?"

Indeed, to many visitors, India is just an inch away from impossibility: crowds and congestion, hassles and frustration. Still, the simple aside became a challenge, a kind of quest. A day, after all, is two dozen hours. Ample time, even in India, but for what? Magic? Adventure? Romance? Retreating to the hotel dining hall with guidebook and maps, I began plotting. Surely the capital of India should be capable of encapsulating some measure of the country's allure. It sounds laughable even now. After all, the guidebooks all offer a similar admonishment: "India is not really a country, but more like a continent."

Still, continents are conquered the same way as tiny territories; piece by piece. The key is a good plan of attack. And an early start.

We rose before dawn the next day, eager for adventure. Our aim was to

visit nearby Agra, home of the Taj Mahal. Five hours from Delhi by bus, the Taj Mahal

could be reached in a couple of hours by private car, but that was too easy for us.

Numerous trains also pass Agra, about 200 kilometers south of Delhi on the way to Bombay.

The best option seemed to be the speedy Shatabdi Express, which does the trip in just

under two hours. Best of all, it departs Delhi at 6:15 a.m., returning around 8:15 p.m.,

facilitating daytrippers like us.

We rose before dawn the next day, eager for adventure. Our aim was to

visit nearby Agra, home of the Taj Mahal. Five hours from Delhi by bus, the Taj Mahal

could be reached in a couple of hours by private car, but that was too easy for us.

Numerous trains also pass Agra, about 200 kilometers south of Delhi on the way to Bombay.

The best option seemed to be the speedy Shatabdi Express, which does the trip in just

under two hours. Best of all, it departs Delhi at 6:15 a.m., returning around 8:15 p.m.,

facilitating daytrippers like us.

So, it was to be 12 hours for the Taj and all. It seemed a bit disrespectful at the outset, but as the day progressed, it turned out to be plenty of time to not only embrace a world wonder, but also sample the full mélange of India's magic.

The train left right on time and provided the first of many delightful surprises. Train travel in India may get mixed reviews from seasoned road hands, but the Shatabdi Express is totally top-notch. As a flaming red Delhi sunrise flooded the carriage, a light breakfast was served on linen tablecloths. The seats were comfortable, and conversation flowed to the steady, soothing rhythm of the rails. Two nearby couples were both headed home to Bombay. By coincidence, both couples were newlyweds, and had just spent their honeymoons in the hill country of Himachal Pradesh, where we had also been. "This is most remarkable, don't you think," one of the men said, clapping his hands with glee. For the entire journey, they regaled us with tales of the Taj Mahal, all the while insisting that we share their biscuits and tasty Darjeeling tea.

Saying good-byes in Agra, we regained our land legs and proceeded down the twisting alleyways of the once grand city. During the time of the Moguls, in the 16th and 17th centuries, Agra was India's capital. Situated on the banks of the Yamuna River, the city does not easily yield reminders of its grandiose past. The traffic is dense, a mass of cars, rickshaws and people. It seems much like any Indian city, until you reach Agra Fort, enroute to Taj Ganj.

Outside the walls, scores of vendors perch on boxes or blankets. They offer a colorful array of goods: religious artifacts, plastic toys, spices and sweets. Fortunes are told, snakes are charmed. The entire sights and sounds of the region are on boisterous display. Inside the fort, the ancient towers, mosque and palace all pay testimony to the magnificence of earlier era.

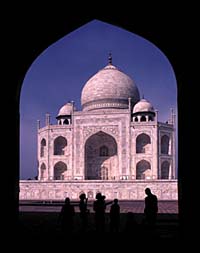

Still, nothing

inside the old fort truly prepares one for the breathtaking first sight of the Taj Mahal,

rightfully considered one of the eight wonders of the world. Perhaps no other building on

Earth has become so recognizable with its republic. Nor can any other building rival its

architectural beauty. Constructed entirely of white limestone, the Taj Mahal has a magical

quality that changes by the moment, with even the most minute varying of light and shadow.

Still, nothing

inside the old fort truly prepares one for the breathtaking first sight of the Taj Mahal,

rightfully considered one of the eight wonders of the world. Perhaps no other building on

Earth has become so recognizable with its republic. Nor can any other building rival its

architectural beauty. Constructed entirely of white limestone, the Taj Mahal has a magical

quality that changes by the moment, with even the most minute varying of light and shadow.

Built over a 22-year span in the 1600s, an estimated 20,000 workers created this Mogul memorial, from Emperor Shah Jahan to his wife, Mumtaz Mahal. The domed mausoleum of white marble is inlaid with gemstones and has four distinctive minarets that provide stunning reflections in a long pond that runs the length of the lush grounds. One can spend an entire day amongst the flowers of the surrounding gardens, watching the Taj Mahal shimmer in the changing light as parades of tourists and schoolchildren pass by.

However, with the clock ticking, we didn't linger long. Instead, we left the Taj Mahal for a quick lunch at one of the many nearby restaurants that provide a bazaar-like, almost biblical flavor to the alleys around the Taj. Then, we hired a car to take us to Fatehpur Sikri, about 40 kilometers away.

Fatehpur Sikri is an old city, predating the Taj Mahal by about half a century. Along the way are numerous other temples, minor palaces and mausoleums that are even older. But age isn't the attraction to Fatehpur Sikri, it's emptiness is. Built in the 1500s, the Mogul city was abandoned soon afterwards. Its old walls, towers, palaces and tombs are remarkably well preserved, creating a four-centuries old ghost town that is a delight to explore.

You won't be on your own, though. Local children and area residents mob all visitors. Few tourists will be able to elude their offers of guide service, and, for a dollar or two, it's hardly worth the effort. Besides, most offer commentary which, even if only partly true, adds mightily to the intrigue of the enchanting site.

While Fatehpur Sikri has been deserted for centuries, the area around the ruins ripples with activity. Descending the stone steps, we dodged several fortune tellers and a monkey dressed in tuxedo. A dozen shrines and temples lined the outer walls, and the roar of supplication was intoxicating. "India has two million gods, and worships them all," noted Mark Twain. "In religion other countries are paupers; India is the only millionaire."

Indeed, there was a richness of activity about us, and soon we were swept into the wedding party. In the distance, we saw our driver waving frantically, but, not-too bothered, we took an hour to disengage from the matrimonial merriment, before tumbling into the backseat, and heading back to Agra.

We arrived late in the afternoon, well before the train journey home. The final hours were spent upon a rooftop of a local restaurant that advertised: "Decent food, great view." It turned out to be as graciously wrong on the first count as it was right on the second.

While we watched the Taj Mahal's white luster fade slowly in the final hours of light, until it became a magical silhouette at sunset, we gorged ourselves on papadoms, dahl and brinjal. The delicacies provided a tasty finale to a wonderful feast of wonders, all within a day's reach of Delhi.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter based in Hong Kong, who wanders around Asia for a number of publications, including the Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, Asiaweek and Time, which ran this story in a special travel section in October 1997.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]