VISIT MYANMAR - NO WAY!

Far from opening up, Myanmar's military regime is trying to woo foreign dollars without any service of democracy. As a result, a worldwide boycott should show that tourism and tyranny don't mix

By Ron Gluckman / Yangon

![]()

W

AY OUT IN THE HINTERLAND OF BAGAN, thousands of crumbling temples attest to the historical greatness of Pagan, the 11th-century capital that has been a virtual ghost city for centuries. A couple of years ago, the military government urged the city's businessmen to build hotels, guest houses and restaurants for a tourism boom that was on the way. Reality? "We've put everything into this," complains a Pagan guest-house owner. "But the rules keep changing. And we're still waiting for the tourists they promised."Pagan, the cradle of Burmese civilization, would be an obvious magnet for any influx of tourists during Visit Myanmar Year 1996, whose delayed launch now is scheduled for November. (The ruling junta has decreed that the country be called Myanmar.) Guest houses and small hotels have been sprouting all over Pagan, 510 kilometers northwest of Rangoon, in a joint initiative between the government and the city's few businessmen.

So far, however, the marriage between public and private sectors has been uneasy in Pagan, and elsewhere. "First they told us to prepare for 1 million tourists, then they said 500,000," grumbles one Pagan entrepreneur. "Then they told us we would have to build our roads and pay for everything ourselves, even the lighting."

For the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), which seized power in 1988, the tourism campaign is a test on two levels: Can it galvanize the country's fledgling private sector, and can it draw in hordes of visitors flashing hard currency? On both counts, the answer looks like a negative. If the tourists do come, moreover, it will be in defiance of a plea by the country's most prominent politician and an international boycott orchestrated by human-rights activists.

Pagan's guest-house owners are not alone in fearing a phantom tourism boom. International hotel chains such as Hong Kong-based Shangri-La Asia Ltd. and New World Hotels International Ltd. have rushed to build showpiece hotels in Rangoon (known officially as Yangon). This year alone, the number of hotel rooms in the capital has bulged by 50 percent in readiness for Visit Myanmar Year.

Even Burma's senior tourism officials concede the promotion could be a bust. "Everybody is a bit nervous," says one official. "We have a lot of attractions, but so many problems. A lot of foreigners are making trouble."

Calls for an international boycott of Visit Myanmar Year continue to gain momentum, often triggered by SLORC's crude repression. In May, for instance, more than 250 pro-democracy politicians were arrested ahead of an opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) congress.

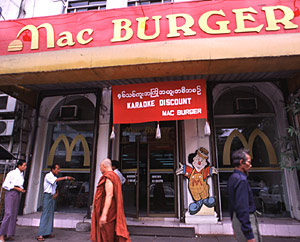

Nor has SLORC shown much flair in promoting Burma as a hospitable destination: In June,

signs denouncing "alien nations" and "foreign interference" appeared

in Rangoon. Such government-inspired anti-foreigner propaganda is commonplace in Burma,

but never before had it been in English and so blatant.

Nor has SLORC shown much flair in promoting Burma as a hospitable destination: In June,

signs denouncing "alien nations" and "foreign interference" appeared

in Rangoon. Such government-inspired anti-foreigner propaganda is commonplace in Burma,

but never before had it been in English and so blatant.

Aung San Suu Kyi, 51, who led the NLD to victory in Burma's 1990 elections only to find herself under house arrest for six years, says the Visit Myanmar campaign is just SLORC propaganda. "We would not encourage anyone to come or support Visit Myanmar Year 1996," the winner of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize told Asia, Inc.

Western human-rights groups have also seized upon the tourist campaign as an opportunity to push for tough sanctions against Burma's military regime. "This is an opportune time to show how the world feels about SLORC and its repressive rule," says an American activist based on the Thai-Burma border. "We are going all out to give SLORC a big black eye."

However, there is little support in Burma for sanctions, especially among local entrepreneurs who are banking on Visit Myanmar Year. "We want people to come in droves," says a Rangoon travel agent. "We need them. We have added buses and printed brochures. We are praying for more tourists."

But few industry analysts expect a huge upsurge in visitor arrivals. For a start, publicity for the Visit Myanmar campaign is not much more than a few unenticing brochures. "We have a very limited budget," concedes Myo Lwin, deputy director general of the Directorate of Hotels and Tourism. "We cannot compete with Thailand and other destinations."

For those visitors who do make it, Burma may offer more history than they bargained for. Soe Tint, general manager of Myanmar Railways, admits that the rail system installed by the British in 1877 is decades out of date. Little maintenance has been carried out since the Japanese occupation during World War II. To clear the backlog of maintenance work would take a decade and cost billions of dollars -- time and money that Burma doesn't have.

Nor is the private sector likely to provide the enterprise or energy to transform Burma into a tourist utopia. Local hotels, for instance, have a lot to learn. Take the Mya Yeik Nyo Hotel in Rangoon, which opened in May. Seven stories high, it has no elevator. Situated on a hilltop overlooking Sule Pagoda, it has no lobby from which guests can enjoy the glorious vista. Instead, it boasts an underground artificial waterfall that gives a musty smell to the new carpets.

Still, government officials refuse to be daunted. Htay Aung, director of the tourism directorate, points to an encouraging increase in air connections. Japan's All Nippon Airways launched a service to Rangoon from Osaka in July, and Royal Brunei Airlines has added a link to London, via Brunei and Abu Dhabi. "We now have over 50 flights a week to Yangon," Htay Aung says. Short-stay visas are issued to tour groups on arrival, and the government is considering extending the facility to individuals.

Many people in Burma believe that simply inviting foreign visitors is a big step

forward. "Visit Myanmar Year will be successful," predicts Bernard Pe-Win, 57,

who owns the Savoy Hotel in Rangoon. After studying at a British university, Pe-Win was

not allowed back into Burma between 1962 and 1977 as the government closed its doors to

the outside world. "Things are improving," he says. "There's more trust

now. The best way for Burma to grow and improve is for more people to come here."

Many people in Burma believe that simply inviting foreign visitors is a big step

forward. "Visit Myanmar Year will be successful," predicts Bernard Pe-Win, 57,

who owns the Savoy Hotel in Rangoon. After studying at a British university, Pe-Win was

not allowed back into Burma between 1962 and 1977 as the government closed its doors to

the outside world. "Things are improving," he says. "There's more trust

now. The best way for Burma to grow and improve is for more people to come here."

Meanwhile, though, Burma's tourism officials are madly rushing to downsize their visitor targets, to try to minimize embarrassment should the promotion prove a monumental flop. The government's current target of about 250,000 to 300,000 arrivals is probably what Burma's tourism industry would have achieved anyway -- without Visit Myanmar Year.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who is based in Hong Kong, but who roams around Asia for a number of publications, such as Asia, Inc., which ran this story in October 1996. For a closer read on Burma's democratically-elected leader, see a transcribed interview that Ron Gluckan did with Aung San Suu Kyi, or another report on Suu Kyi. To look at some of his other stories on Burma (or Myanmar), please click on Down and Up in Myanmar, Rock 'n' Rangoon, Tracking Myanmar or Where have all the Opium Poppies Gone?

![]()

To return to the opening page and index

push here

![]()

[right.htm]