Space Race is on. Again...

Roll over Buzz Aldrin, because China is back in the space race, with its eyes on the Moon. And beyond.

By Ron Gluckman/Beijing,China

FEW EVENTS OF THE LAST HALF CENTURY seem as defining as the Soviet launch of the first satellite on Oct. 4, 1957. Competing Cold War powers scrambled to build and blast boosters of their own.

The race for space was on, with

rhetoric rocketing. After the U.S.S.R. upped the ante with a man in orbit in

1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy conceded that America had been beaten into

space, but vowed to be the first to the moon.

The race for space was on, with

rhetoric rocketing. After the U.S.S.R. upped the ante with a man in orbit in

1961, U.S. President John F. Kennedy conceded that America had been beaten into

space, but vowed to be the first to the moon.

China's response was infinitely more subdued. "How can we be considered a great power?" Chairman Mao reportedly moaned. "China cannot even put a potato in space."

Yet, 45 years after the launch of Sputnik turned science fiction into fact, China may be ready to readdress its galactic deficiency. At last month's opening of National Science Week in Beijing, Chinese officials not only boasted that they would soon send men into space, but eventually build moon bases, a space shuttle and mount missions to Mars.

The pronouncements were made at Beijing's Millennium Monument, where a large exhibit of mainland achievements was mounted behind a banner proclaiming: "2002 -- Future on Science."

Despite the space-age airs, the exhibit was a typical Middle Kingdom hodge-podge: dog robots and innovative speech-recognition demos side-by-side with shameless pitches for household appliances from Legend. Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility showed models of a photon absorber and dipole magnet alongside an exhaustively detailed but baffling display on coffee making by Nescafe.

The real jolt, though, didn't come from caffeine, but from a jumble of George Jetson-style buildings and garden domes, sprawling across an eerie landscape. Parked nearby was a large metallic dune buggy, perfect for exploring out of the way places -- like other planets.

Undeniably simplistic, this model of a Mars colony, complete with mining equipment, underscored China's enormous ambitions for space. "We will explore the moon certainly," Ouyang Ziyuan, a chief scientist with China's space program, told reporters.

He said China aims to establish a

space station by 2005, permanent moon bases later. These could provide raw

materials for further exploration and erecting space colonies. "Whoever conquers

the moon first will benefit first."

He said China aims to establish a

space station by 2005, permanent moon bases later. These could provide raw

materials for further exploration and erecting space colonies. "Whoever conquers

the moon first will benefit first."

Some may quibble. After all, it's been nearly 33 years since Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin planted the U.S. flag on the moon. Still, scientists around the globe and space enthusiasts like Mr. Aldrin are buzzing about the possibility that China's great lunar leap may reclaim the final frontier from its sad status of late as a forgotten frontier.

Besides, China is no newcomer to the space race. Inventor Wan Hu allegedly made man's first space flight in the 16th century, albeit briefly. Strapped to a chair studded with rockets, Wan blasted off -- into oblivion.

Several Chinese satellite launches in the mid-1990s did likewise, prompting many to ponder whether plans for manned flight might not be rushed. After all, the Americans and Russians attempted dozens of missions before risking, as one early astronaut quipped, "a man in a Spam can."

Others say Beijing has been methodical in its space program. "China is racing nobody but itself," says Charles P. Vick, chief of the space policy division of the Federation of American Scientists. "I think they are very safety conscious."

And,

despite light speeds associated with space travel, there is still much a

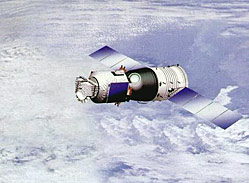

tortoise can learn from the hares. Take China's Shenzhou ("Divine Mission")

spacecraft, first put in test orbit in 1999. Analysts say it's adapted with

Russian help from the Soviet Union's Soyuz spaceship, itself modeled on

America's Apollo.

And,

despite light speeds associated with space travel, there is still much a

tortoise can learn from the hares. Take China's Shenzhou ("Divine Mission")

spacecraft, first put in test orbit in 1999. Analysts say it's adapted with

Russian help from the Soviet Union's Soyuz spaceship, itself modeled on

America's Apollo.

The two-part design includes orbital and entry modules. By fitting the former with docking adapters and leaving them in space, China has been able to practice docking maneuvers. Several could be linked together to form a Lego-style space shuttle, which analysts believe is the Chinese intention.

Beijing has been mum about a launch schedule, but most experts believe a manned mission is only months away. "China has been talking about putting men into space for a decade," says Dr. John M. Logsdon, head of the Space Policy Institute at the Elliott School of International Affairs, "so it's no surprise to anyone who has been paying attention."

As to the moon and Mars, however, he adds: "I frankly discount the Chinese discussions of a rapid move to moon bases. The capability to put people in orbit is a large step from the yet-to-be demonstrated capability to put people in low orbit. I think the moon-Mars rhetoric is just that -- rhetoric."

Mr. Logsdon points out that the cost of shuttles, moon bases and Mars landings is likely beyond the means of China, or any single nation. "The crash U.S. effort to put a man on the moon cost over $100 billion in today's dollars ($23 billion then)," he says. "A mission to Mars has been priced in the U.S. anywhere from $10 billion to hundreds of billions."

China has made no secret of its intention to join the fraternity of

space-faring nations. It has been putting payloads into orbit with its Long

March rockets since 1970. The first Shenzhou spent 12 hours in space in late

1999. Thirteen months later, Shenzhou II was used to separate and reconnect

modules by remote control repeatedly over two weeks.

China has made no secret of its intention to join the fraternity of

space-faring nations. It has been putting payloads into orbit with its Long

March rockets since 1970. The first Shenzhou spent 12 hours in space in late

1999. Thirteen months later, Shenzhou II was used to separate and reconnect

modules by remote control repeatedly over two weeks.

Shenzhou III orbited Earth over a hundred times before the capsule touched down safely on April 1. The date is an odd coincidence, because China's space aims are no joke. Most believe men will board either Shenzhou V or VI later this year or next.

All astronaut candidates have "the right stuff" -- with Chinese characteristics. But mainly they're small. None are taller than five and a half feet or over 110 pounds, according to Su Shuangning, commander-in-chief of China's manned space navigation project.

He recently confirmed a dozen former pilots are ready for flight. They will boldly go where only a rabbit, monkey and dog have yet been -- on a Shenzhou as passengers. China has also sent plants into space, part of its research for feeding future colonies.

No word on potatoes, though. Still, Mao would be proud.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has been roaming around Asia since 1991, when he was based in Hong Kong. Since 2000, he has been based in Beijing, covering China for a wide variety of publications including the Asian Wall Street Journal, which ran this in the Weekend Edition June 7-9, 2002.

Check back for a larger, more thorough investigation of China's space program, for science publication Seed Magazine, on the stands in September 2002.

Picture credits: 2002 by RON GLUCKMAN; rest from the web.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]