China's Grave Memories

In the Middle Kingdom, history is all mixed up because of so many periodic revisions, yet a serene cemetery in the center of the city proves that Beijing cannot bury its past

By Ron Gluckman/Beijing

BODIES BECOME A DIME-A-DOZEN among 5,000 year-old civilizations, so it's really no surprise that Beijing is famous for its tombs. Tour buses roam the graveyard circuit: Ming tombs, Qing tombs. Even Mao Tse Tung himself is enshrined on a velvet cushion in his stately Tiananmen Square mausoleum.

But dead center in a reclusive campus in the west of the capital simmers an old quagmire that literally refuses to be buried from view.

Shaded by pine trees, hidden behind walls and locked gates, rests a secret Communist Party crypt that has haunted officialdom for decades--the unspoken skeletons in China's closet.

Although the graves of five dozen Western pioneers in the Middle Kingdom have

been talked about for ages, they have seldom been seen. Suddenly, it's possible.

One merely makes a booking with the Communist Party School, the unlikely host of

these historic tombs.

Although the graves of five dozen Western pioneers in the Middle Kingdom have

been talked about for ages, they have seldom been seen. Suddenly, it's possible.

One merely makes a booking with the Communist Party School, the unlikely host of

these historic tombs.

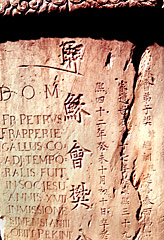

One plot holds three huge stele and headstones marking the final resting place of the China's first and foremost Western visitors: Matteo Ricci, Ferdinand Verbiest and Adam Schall.

Nearby, in a separate graveyard, stand markers of 60 other missionaries, from Italy, Portugal, France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the present Czech Republic and Slovenia.

These were some of the West's brightest brains and bravest explorers. Old China Hands around the globe have dreamed for decades of such a pilgrimage.

The grave-keeper wiggles a key and talks about plans to open a small museum dedicated to Matteo Ricci, perhaps timed to the 400th centennial of the Italian Jesuit's arrival in Beijing this year.

Already, the Association for Matteo Ricci Studies of China has produced a

fine book about Ricci and the colleagues lying at his side. That is remarkable,

considering China has obscured Ricci's role in its history for much of the

century.

Already, the Association for Matteo Ricci Studies of China has produced a

fine book about Ricci and the colleagues lying at his side. That is remarkable,

considering China has obscured Ricci's role in its history for much of the

century.

The property had been in Catholic hands for four centuries, the Emperor's gift to Ricci for his contributions to China. But when the communists took over, they displaced the Catholic seminary, too, establishing the Beijing Communist Party School, where high-ranking officials attend brush-up classes on bureaucracy.

Ricci wasn't the first Westerner to visit the mysterious Middle Kingdom, but he made the greatest mark. As early as the 16th Century, he published the first maps of China available in the West. But Ricci is more renowned for what he brought China--Catholicism, of course, but also Western methods of mathematics and astronomy.

These scientific skills, along with a dedication to learning the Chinese language and culture, won Ricci an unprecedented place in the Emperor's court. In 1600, he became the first Westerner allowed to reside in the capital. When he died 390 years ago last month, he was buried here.

Others, like German Schall and Belgian Verbiest followed Ricci East, bringing telescopes and books of trigonometry. The instruments and science texts were prized by the admiring Chinese, and many of the antique instruments are displayed atop the old Watchtower that once guarded the city walls. Now it overlooks traffic jams on the highway paved over those very walls.

Astronomy was much revered in ancient China. Religion, however, wasn't, and the missionaries had a tempestuous tenure in the Middle Kingdom. To be fair, it was that way long before the Communists, who certainly didn't invent the practice of religious persecution.

But Beijing, in keeping with its customary ambivalence towards all things Western, has attempted to erase all mention of the foreign missionaries from history. Which makes the cemetery an uncomfortable monument in many ways--hence, the locked gate and un-welcome mat.

Another reminder is inscribed on a cemetery wall. In bas relief, hidden from view, is written perhaps the world's largest apology, for injuries inflicted by the Boxer Revolution, which ended a century ago.

Few in the West are likely to remember this terror, when countless missionaries were slaughtered and churches across China put to the torch. But China is still buffeted by conflicting emotions regarding its past: an apology written, but hidden to all.

For centuries, it's been thus, a roller-coaster of indecision. These graves

were desecrated during the Boxer period, when the seminary was razed. All that

remains is an old clock tower and a small stone chapel; the Communist Party

Redecoration Committee replaced the cross with a Communist Star and shattered

all the stained glass. But though cemented over, the arched windows and other

features are instantly identifiable.

For centuries, it's been thus, a roller-coaster of indecision. These graves

were desecrated during the Boxer period, when the seminary was razed. All that

remains is an old clock tower and a small stone chapel; the Communist Party

Redecoration Committee replaced the cross with a Communist Star and shattered

all the stained glass. But though cemented over, the arched windows and other

features are instantly identifiable.

That the chapel still stands is remarkable. Likewise the tombstones, perhaps the only remaining graves of foreigners in all China. In Shanghai and Harbin, which had larger foreign enclaves, Western cemeteries were long ago razed and the bones scattered.

That might have happened here. But students stood up to the Cultural Revolution thugs, the grave-keeper says proudly, ferrying away the tombstones to bury, thereby saving them. The cemetery, he says, was restored in 1978.

Still, don't expect a rush of religious tourism anytime soon--at least not around these tombs. Instead, Beijing will reopen East Church in September, after a nearly US$2 million restoration. Some say it's simply a tool to lure tourists to nearby Wangfujing shopping district.

Indeed, Beijing remains at odds with the Vatican on so many issues, from basic religious freedom to the appointment of state-sponsored ministers and bishops, who aren't recognized by the pope. Beijing's battles with the church are only part of the age-old jingoism that has always marked its dealings with outsiders, or barbarians, as they are still known.

Foreigners living in the capital don't need a Belgrade bombing or resulting riots to remind them of the precarious balance. Only last month, Beijing waxed hysterical about the sale of some ancient Chinese treasures by international auction houses in Hong Kong. Despite the vitriol, the auctions went on.

Local papers praised the "Chinese patriots" who purchased some of the pieces, looted by foreign armies from the old Summer Palace, and returned them to Beijing.

Now, these bronze heads are exhibited by the Poly Art Museum. Thousands of visitors have already flocked to see the much-hyped nationalistic icons.

But what is never mentioned is that the artifacts were sold in the first place by a Chinese collector, and in China's own Hong Kong. And the heads, just like the unlabeled astronomical instruments at the nearby watchtower, were actually the work of China's old friends, the Jesuits.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has been based in Hong Kong since 1990, when he began visiting China for a wide variety of publications, such as the Wall Street Journal, which ran this story in July 2000.

Pictures by Ron Gluckman and Jolanda

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]