LIFE UNDER SIEGE

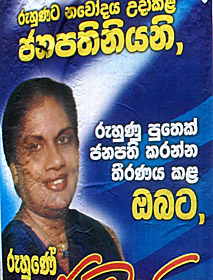

Chandrika Kumaratunga took up her dynastic family's mantle promising an era of peace and prosperity. Two years later, Sri Lanka's civil war rages on, the economy is faltering and the president's support is plummeting. Ron Gluckman spent three weeks as her shadow to try to discover how such lofty ideals had become grounded

By Ron Gluckman / Colombo

C

HANDRIKA KUMARATUNGA IS HALFWAY through a mid-term self-critique of her four major policy goals when death jarringly intrudes. The president has already detailed her efforts to reverse Sri Lanka's grim human-rights record and curtail its equally atrocious tendency toward corruption."Third, is the war and the ethnic problem," she says. Almost on cue, the door opens and her secretary slips into the room. Tension fills the chamber, but the president pays no notice. Struck and scarred so often by tragedy in this terror-torn land, the loquacious leader is on a roll, and her secretary dares not interrupt the private interview.

Kumaratunga is recalling how, early in Sri Lanka's 13-year civil war against minority Tamil rebels in the north and east, she and her husband defied government pressure and death threats to independently talk peace with Tamil leaders, including Velupillai Prabhakaran, head of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). "We will see that you get a fair deal," she recalls promising.

"All the other four groups agreed [to negotiate] -- and all their leaders were murdered by the LTTE." A solution to the ethnic crisis was a key plank in her election campaign two years ago, but it was no idle promise. "As far back as 1986, I have been talking peace," she says.

The secretary, who has been inching closer, finally leans over to the president's ear. The terrible news is passed in a tiny whisper, but my tape recorder catches it: "There has been an incident in Jaffna. A suicide bomber . . . ."

Minutes ago, a woman triggered an explosion at a ceremony hosted by Housing Minister Nimal Siripala de Silva, who is overseeing the rebuilding of Jaffna, the northern rebel headquarters recaptured from the Tigers by government troops in December. De Silva has miraculously survived, but three dozen others are dead. Among them: Maj.-Gen. Ananda Hamangoda, head of the army in Jaffna, and a friend of the president. Once again, a kamikaze killer has marked Black Friday -- anniversary of the first suicide bombing in 1987 -- with bloodshed. And once again the target has been painfully close to the president.

There is a brief moment of shock for this woman, who is perhaps world terrorism's No. 1 target. Then Kumaratunga reacts like a leader in some classic war film: confident and composed. Overruling my offer to end our interview, she orders me to remain. Moving to her desk, the president grabs one of the half dozen phones and begins making calls, to the military and the victims' families. Then, calmly, she returns to our conversation, picking up exactly where she left off, speaking eloquently and convincingly for another 20 minutes.

Clearly, Kumaratunga is not the kind of leader who wilts in a time of crisis. But even her closest friends wonder how she is able to hold up under the constant pressures. Her current concerns include the fate of the army's advance toward the northern Tiger-held town of Kilinochchi. So far, the fighting has left over 200 people dead and forced some 155,000 from their homes. In all, more than 50,000 Sri Lankans have been killed since the start of the Tamil uprising in 1983.

The civil war is but one of the challenges this fairy-tale president has had to face since she swept into the office she seemed destined to rule from birth. Indeed, few leaders in the world can match her political lineage. Or her personal sacrifice.

Kumaratunga was only 14 when her father, Solomon Bandaranaike, who was then prime minister, was assassinated by a Buddhist monk in 1959. The teenager was to learn first-hand from her mother about fortitude. Sirimavo Bandaranaike became the world's first female head of government after her husband's death, prophetically paving the way for Kumaratunga's equally tragic rise to power.

Political dynasties are common to Asia, but Kumaratunga did not receive the presidency on a platter. After a stint at the University of Paris, she returned energized by European ideas and the bluster of the 1960s youth movement.

"I've been a rebel all my life," she says. But friends say she grew into the rebel role. They remember a girl who played piano, wrote poetry and participated in school plays. A different Chandrika came home from college less concerned about conformity than blazing her own political path.

She found a partner in dashing matinee idol Vijaya Kumaratunga; they wed in 1978. The handsome movie star quickly became a popular politician, heading the leftist Sri Lanka Mahajan (People's) Party, formed by the couple when they split from her mother's Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) in the late Seventies.

The new party's life span coincided with the

dawn of Sri Lanka's darkest period. The Tamil war -- sparked in 1983 by ethnic riots and

government-sanctioned massacres -- was followed by the outbreak of the radical Janatha

Vimukthi Peramuna uprising in the south.

The new party's life span coincided with the

dawn of Sri Lanka's darkest period. The Tamil war -- sparked in 1983 by ethnic riots and

government-sanctioned massacres -- was followed by the outbreak of the radical Janatha

Vimukthi Peramuna uprising in the south.

By the end of the 1980s, the once-serene land of Ceylon headed international lists of human-rights abuses. Kumaratunga describes this as a period of national madness, "when the government unleashed violence on the Tamil people and killed them and burned them alive."

Yet journalist Percy Seneviratne recalls: "The image that even now burns bright in the minds of many Sri Lankans is of the courageous widow, clenching her hands in a demonstration of utter defiance over the bier of her husband." That widow was Kumaratunga.

In 1988, husband Vijaya was gunned down, and died in her arms -- four days before their 10th wedding anniversary. Fearing for the safety of her two children, Yasodara and Vimukti, Kumaratunga fled to Europe.

She returned in 1992 to inject new life into her family's moribund SLFP. Her rise was meteoric. Elected chief minister of the Western Provincial Council in May 1993, she challenged and won general elections the following year. After briefly serving as prime minister, she became president in November 1994, ending 17 years of rule by the United National Party (UNP).

Kumaratunga claims that she never had political ambitions, preferring to work toward specific goals, such as land reform. Others see it differently.

"She was always interested in politics, even as a child," says one family friend. The middle of three children, Kumaratunga exhibited an early curiosity about government, he adds, and was close to her father.

Still, most Sri Lankans expected younger brother Anura to be the next ruler in the family. That always seemed his hope. The two siblings, four years apart, have been at odds since Kumaratunga returned from Europe. Anura defected to the opposition once it became apparent his mother had anointed Chandrika heir of the family's political dynasty.

Although Kumaratunga returned the favor, making her mother prime minister for an unprecedented, but largely ceremonial, third term in 1994, it is an uneven alliance. Mother and daughter are polar opposites. Kumaratunga speaks her mind in spontaneous outbursts. Her lively, mischievous manner contrasts starkly with her quiet, calculating mother. A shrewd strategist, Bandaranaike, 80, is nonetheless blamed by many for leading Sri Lanka into economic isolation, eschewing investment opportunities with a fervor for old-fashioned nationalism.

And no matter how many saris Kumaratunga wraps around her stocky frame, and despite her public expression of the Buddhist faith, few see her as anything but a Western outsider next to Mrs. B., as her mother is known. The current rumor sweeping Colombo, in fact, is that Kumaratunga is a wild swinger who parties late and who has secretly married.

"The whole of Colombo is talking about this. Did you hear?" Kumaratunga shouts. "I'm supposed to be married!" Although she chuckles, and tells several stories mocking the Sri Lankan tendency to gossip, the behind-the-back chatter clearly stings. She is currently suing one newspaper because it reported, as she recounts, that the president is "sexually very immoral, she sleeps around with lots of men. She spends her time getting drunk, that's why she's late, and she hardly works, she has a whale of a time." Kumaratunga says another paper suggested that she "crept into some bachelor's birthday party at 12:30 midnight, through the back gate . . . and I stayed there until 2:30 in the morning!"

Such tales can be dismissed as tabloid trash, but other reports demand more serious scrutiny. For instance, Kumaratunga was criticized recently for being overseas when the LTTE set off bombs in a Colombo train station and wiped out the entire northeastern army base of Mullaittivu, leaving at least 1,200 dead. Though the president was supposedly on an official trip to London, she was later reported in Egypt with her children and had to cut short her holiday.

Bandaranaike herself has disagreed often with her daughter, conveying the opinion that Kumaratunga is sometimes reckless in her presidential judgment. Yet, in a taped interview, Mrs. B. says: "People are very demanding, you cannot satisfy them all . . . I feel sorry for Chandrika; she's trying her best."

By all accounts, the family is quite supportive. Despite the rift between the president and her brother, the whole family has until recently lived together in their three-house compound on Rosemead Place, a tiny lane in Colombo's exclusive Cinnamon Gardens district.

Both mother and daughter are products of the same rigid schooling at St. Bridget's Convent. Set among Cinnamon Gardens' broad tree-lined boulevards, the 94-year-old academy is "reputed for its discipline," according to its stern headmistress. She meets me at the gate and guides me through a mass of giggling girls, who wear white uniforms and bow to passing teachers.

I am introduced to Chandrani de S. Kulasiri, one of Kumaratunga's former teachers. "Chandrika was a very good student," Kulasiri recalls. "She was very mischievous and talkative, but lovable and intelligent." Even as a teenager, she says, Kumaratunga was a good organizer, full of energy and very positive. "She was very talented. I remember especially that she wrote a wonderful essay. It was right after her father's death. It was on capital punishment; whether it should be abolished. She gave a very good argument that no one should be allowed to take anyone's life."

Her liberal outlook only broadened when she returned to Sri Lanka to join her mother's second regime; Bandaranaike was prime minister from 1960 to 1965 and 1970 to 1977. Exhibiting the idealism that fans say is her greatest strength -- critics are not quite as kind, calling her pig-headed -- Kumaratunga took over the land-reform program with zeal. Something of a young Marxist, she immediately targeted the large holdings of the island elite, beginning with her own family.

"We used to own a lot of land," says the president, 51, reclining on a blue sofa at the presidential palace during an intimate interview. "Mother is perhaps the only politician who actually brought in a law when she was head of state which took away her own wealth, which was land." Kumaratunga says her years at the land commission were among her finest. "That was exciting because it was a limited area of responsibility." She recalls spending weeks in the field, often driving up to 5,000 km a month. There were sunsets, barbecues on beaches and lots of free time. "Nowadays, there is no time," she says wearily.

The window is open and birds chirp in trees shading a fountain filled with fish. It is a rare moment of calm for Kumaratunga, who has shooed away her aides and banished a television crew from the meeting room. Ignoring the constant ringing of phones, she talks at length of her youthful love for music. She used to play guitar and piano: "Silly things," she says, smiling at the recollection. "Like Dean Martin and Elvis Presley." But there is little time now for such indulgences. Likewise for past passions such as pottery, poetry and painting.

Her greatest regret, she says, is the lack of time for reading. She says she prefers thick, serious novels. But an aide confides that the president also likes romance movies. On a recent overseas flight, they chose "The Bridges of Madison County" and "The Scarlet Letter." Both films are tearjerkers. "I was awash in tears," the aide recalls, but remembers this: The president did not cry. "She's tough, and resilient," the aide says. "She can take a lot, but I wish people knew how much she cares. She's genuine, not a big show. She has a huge heart."

The aide adds that the president's greatest weakness is a tendency to try to do too much. Running a country plagued by ethnic strife, terrorism, power outages, water shortages and an economic slowdown can be overwhelming. So are the security constraints. When she travels, as many as six convoys, led by police cars and jeeps filled with heavily armed commandos, leave the presidential palace in tandem. They go in different directions to confuse would-be assassins. Hundreds of troops line the road, stopping traffic and standing guard every 50 meters.

Then there is the smoke screen of press releases about invented appearances and bogus trips abroad. "I really feel for her," says presidential secretary Diane Inman. "I also have two children, but I guess it's different for her. Every day since she was born, she's been in politics." Yet the president's own sister, Sunethra, says: "We were in the public eye all the time, all our lives. It was always a terrible nuisance for all of us."

It is part of political life in a land where assassination and suicide bombings have become regular events. "I'm supposed to be the leader who is most at risk at the moment, the most wanted leader by terrorists in the whole world," says Kumaratunga. Her only escapes are secretive visits to the family home. "I love gardening," the president says, her face growing soft as the afternoon sun sweeps across the sofa. She describes growing coffee, pepper, cloves, coconut and general foliage on a 20-hectare plot.

In Sri Lanka, it is common to question whether any politician is motivated by sincerity or the sake of appearances. Yet impartial observers as well as friends say Kumaratunga is genuine. "The president has an incredibly strong sense of commitment to public duty, and part of that comes from her background. Both her parents were prime ministers and there was never a breath of scandal about either of them," says Lakshman Kadiragamar, a renowned lawyer whom Kumaratunga named minister of foreign affairs. Often considered the nation's second-most powerful person after the president, he had no previous political role and, in fact, did not even know Kumaratunga before his posting.

The same is true for many of the key members of the Cabinet. "I only met her last August," says Thilan Wijesinghe, a 36-year-old financial whiz. A month afterward, he became chairman of the powerful Board of Investment. As outsiders, both are untainted by the charges of corruption leveled at most Sri Lankan politicians. Still, both were gutsy choices; Wijesinghe because of his age, Kadiragamar because he is Tamil.

Not only is Kumaratunga brave and idealistic, she is also bursting with energy. To my original request to follow her for a few days, she issued this challenge: "You can come along one day and, if you can keep up, you're welcome to try another."

Indeed, it was a challenge, as I discovered over a grueling 20-day period. Her nights always end past midnight. "I think I'm left with 30% or 40% of my youthful idealism. I'm down to about 60% at least." Then she flashes her million-dollar smile. "About 15 years ago, I thought I could change the whole world," she says. "I think you do need people like that to change the world, otherwise the world never changes."

Known as a workaholic, Kumaratunga is a hands-on politician who displays a keen enthusiasm for even the tiniest detail of government. When a local energy consultant brings a proposal for an ambitious solar project before the Cabinet one afternoon, the president leads her own energy officials in the questioning.

However, delegation is a problem -- she retains two key portfolios for herself: defense and finance. Overall, she seems overly ambitious, stacking appointments and keeping staff and visitors waiting, often for hours at a time.

Her tendency to tardiness has become a national complaint. On a state visit to India last year, she kept President Shankar Dayal Sharma waiting for 40 minutes -- even though she had no appointments beforehand.

The subject is a topic in the presidential palace too. "She'll be coming soon," a member of her 700-man security team advises me one day. An hour later, all he can offer is, "Soon." Still later, he strolls by chuckling: "Very soon, I think."

Some say her tardiness is a sign of inexperience and inefficiency. An otherwise admiring Colombo diplomat is blunt: "She's serious about shaking things up, but the question is, how much is she really accomplishing? That's the downside of her government," the diplomat says. "She's just not administering well. As a result, it's a weak government."

Indeed, despite great gains in some areas, Kumaratunga has rapidly squandered the goodwill that followed her electoral victory two years ago. It is clearly frustrating to a president with such genuinely good intentions. But results count more in the real world.

Unexpectedly, her greatest success has come on the battlefield. Pledging to bring peace to Jaffna within a year, Kumaratunga found herself reluctantly leading the nation to war after the Tigers abruptly broke off talks, returning to a terrorist campaign that continues to kill scores month after bloody month. While Kumaratunga has stunned even the staunchest hawks as the army brought rebel-held Jaffna under government control for the first time since 1989, the war has drained state coffers and destroyed the economy by scaring away foreign investment and tourists.

Even Mother Nature seems aligned against the president. Sri Lanka is highly dependent on hydroelectricity. But this year, the monsoons never came. Besides severe water shortages, Sri Lanka has been left with insufficient power, resulting in daily four- to eight-hour blackouts. The situation was not helped by the LTTE bombing of a crucial oil refinery outside Colombo last October, nor by a crippling electrical workers' strike earlier this year.

"The war was bad, but things are much worse now," says one Colombo resident. "Before, it was happening in Jaffna. Even with terrorism, when it's a building, unless you were in that building, it really didn't affect you. But with the power and water problems, the war came home to everyone. You wonder what next: the phones, the roads, the beaches?"

Indeed, the country's infrastructure is falling apart, and critics contend that the president has no viable plan to rebuild the economy. "Her regime is gripped by a terrible inertia," says a veteran journalist in Colombo. "No decisions are being made, no motion is going on." Adds an economic analyst: "In some ways, the country is actually moving backward."

That is the mood on the street too, where residents have watched Sri Lanka's annual economic growth of 10% to 15% dwindle to official rates of about 5%. Independent analysts say the real figure will likely be under 4% this year. Meanwhile, prices are rising faster than wages, and the war in the north rages on with mounting casualties and no end in sight.

"People are getting fed up," says a government worker, noting that dissension is keen within the ranks. "Kumaratunga promised to end the war and hold elections within a year; she did neither. The voters are getting tired of her. They wanted change and have gotten nothing. She's lost all of her support."

Even her ambitious plan to grant greater autonomy to the Tamils may fail to yield much goodwill. Last month, a private bargaining session revealed that Kumaratunga has not even secured the backing of moderate Tamil leaders. And members of the influential Buddhist clergy continue to stir simmering racial tension with complaints about the erosion of the island's territorial integrity.

Meanwhile, the opposition UNP has found a comfortable position straddling the fence. Although clearly lacking the presence of former president Ranasinghe Premadasa, who was assassinated in May 1993, party chief Ranil Wickremesinghe possesses movie-star good looks and a growing sense of stature among voters. "If she held an election today, she'd lose," Wickremesinghe boasts. "Her government has not managed this economy at all. It's a disaster. She's incompetent; she's provided no leadership to this country."

I got a glimpse of how much this regime's appeal was slipping at the president's own home. Kumaratunga hosted a party for 150 of Sri Lanka's most influential lawyers -- and one visiting reporter. The lawyers were among her biggest supporters in elections two years ago, yet I was soon surrounded by a hissing mob. "The lady has lost her grip," says one visitor. Adds his friend: "The president is ineffective. She has become our biggest problem."

Surely this was not what the president had in mind earlier in the day, when she told me: "These are my most loyal supporters. It will be good for you to hear what they say."

It is just one more case of bad judgment for Sri Lanka's bad-luck president. For all her energy, idealism and dedication to human rights, Kumaratunga comes off most like Asia's version of former U.S. president Jimmy Carter. Her goals are impeccable, but her execution, thus far, seems faulty.

Kumaratunga is stubbornly self-righteous like Carter and, to her immense credit, just as high-minded about human rights and justice. But unless she learns to be a better politician, she seems set to follow Carter's lead and be remembered not as the crisis-solver that Sri Lanka cries out for but as one of the finest leaders Asia never had.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has been living in and covering Asia since 1990. This story was a cover feature for Asiaweek in August 1996. For a look at some of Ron Gluckman's other reports from the island, see tourism, solar chimney, war zone and Arthur C. Clarke.

Chandrika Kumaratunga has survived as a politician, scraping by with a series of risky maneuvers, but piece continues to elude Sri Lanka as the killings continue. Several people interviewed for this story have, in fact, been assassinated, including Lakshman Kadiragamar, who was gunned down in his home when I was last visiting Sri Lanka, in August 2005.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]