LOCKED IN TIME

Chinese immigrants flooded to California, chasing the elusive Gold Mountain. Few found a fortune in the mines, but they made California a prosperous state by helping to tame the West, pounding railroad ties and dredging canals that created the nation's richest farmland. Hard work, but solace came in small Chinese towns, where they lived, prayed, gambled and played mahjong. All those towns are gone, save one, and Locke is fighting a losing game with time

By Ron Gluckman /Locke, California

S

EVENTY-FIVE MILES FROM SAN FRANCISCO is a town sleepwalking from another century. Sidewalks are wooden. Ramshackle buildings with peeling paint whisper tales of the gold trade, when pleasure was peddled in the bordellos, saloons and gambling parlors.The Tule mist that sweeps through the reeds of the river delta adds a grey coat to the ghost-town image of Locke, where the Wild West spirit has never been tamed.

In Locke, the date could easily be 1940 or 1880.

And the cowboys riding this river range were all Chinese.

Locke is the only rural Chinese village remaining in the whole of America. While Chinese districts survive in several American cities, none claim the unique ethnicity of little Locke.

The three-block town is an anthropological treasure, the last

independent enclave built by and exclusively for the Chinese. In the layers of dust on

Locke's decaying streets, one can mine the memories of the first Chinese  immigrants, who came searching for Gum Shan, the Golden Mountain. When the gold

mines closed, they laid the ties for railroads that spanned the continent.

immigrants, who came searching for Gum Shan, the Golden Mountain. When the gold

mines closed, they laid the ties for railroads that spanned the continent.

During the shameful years of suppression, the "Driving Out," when Chinese were forced into railroad cars in Seattle and Tacoma, massacred in Los Angeles and Wyoming, they found shelter in the farmlands of California's Central Valley. The flooded Delta marshlands needed reclaiming. Here was work too dirty for the whites, so the Chinese were once again welcome.

Chinese villages dotted the Delta. In fact, this is the only area in North America that can claim a continuous Chinese presence for over 125 years. They built the levees that made this the most productive agricultural land in America. Here, they were safe from the racial violence, left alone to sow asparagus and pears and potatoes, backbreaking work for $1 a day. Pitiful pay, perhaps, but enough to lure thousands more from China.

Most settlements were gradually assimilated into the suburban sprawl of ranches and housing estates that now line the banks of the river as it twists dramatically south of the state capital of Sacramento. Gone are the Chinatowns of Isleton, Walnut Grove, Rio Vista and Courtland. Only Locke remains a monument to that rip-roaring era, when the town boasted three casinos, untold opium dens, five whorehouses and not a single officer of the law.

Time has taken its toll. Locke's aged Chinese residents number less than two dozen, and those are slowly dying out. Locke's new generations went away to college and never returned. Craftspeople have taken their place, weaving the river reeds and running art galleries that cater to the 10,000 or so curious tourists who annually visit the quaint settlement.

Many fear Locke itself could disappear. The entire Chinese village and surrounding farmland was bought 15 years ago by a foreign investor, who wants to build 72 homes nearby, financing a scheme to turn Locke into a tourist town.

The proposal has been mired in controversy with combatants splitting along predictable lines. The state seeks to protect Locke, listed as a National Historic site. Local shop owners and academics urge strict government control. The battle has had ugly episodes, with charges of cultural ignorance, even racism, fired at the foreign developers, who are accused of putting profits ahead of concerns for the indigenous integrity of the town.

The confrontation is classic, except, in Locke, the roles are reversed. The self-styled saviors of the Chinese town are almost all caucasians. And the new owners are Chinese.

Hong Kong developer Ng Tor Tai bought the entire town and 450 surrounding acres in 1977. His Asian City Development company has repeatedly been stymied with grand plans for the property, which include creating a huge lake to supply the subdivision, upgrading services to Locke and creating an Asian theme town there.

"This town hasn't changed much since we bought it 15 years ago," says Clarence Chu, brother-in-law of Ng and general manager of local subsidiary, Locke Property Development, Inc. "Our goal is to develop the property for residents and to satisfy tourists. We want to improve the town."

Indeed, contrary to charges of carpet bagging, it would be hard to pin anything on Asian City other than an incredible capacity for patience. Chu, born in Guangzhou and raised in Hong Kong, moved into the little town, where he runs the River Road Art Gallery. Over the long, frustrating years of negotiation - the state agreed to buy Locke in an ill-fated scheme in 1980 - Asian City has tinkered little with the town, except to encourage the repair of storefronts and spur small-scale business development. Because of the unusual deed to the property, Asian City only owns the land, while tenants own the buildings themselves, which has hampered renovation efforts.

Asian City's major alteration has been the restoration of Locke's original schoolhouse, where news items are posted in English and Chinese and a huge world globe showcases the Chinese perspective prior to the communist revolution.

Yet, Chu's dutiful daily work routine and Asian City's restraint has failed to win a rapport with local residents.

"We don't want development," says Gail Burns, who works at the Dai Loy Museum, once a casino. On display are iron knuckles and lead pipes used to deter bad losers. There are photos of Sun Yat-sen, father of the Chinese republic, who visited in 1912 to raise funds for his nationalistic movement. Other photos show Chinese residents tilling the land, pruning pears and packing cans.

"Can you see new houses here? It would ruin Locke," says Burns, an Australian who relocated to the river town two years ago. She is typical of the urban exiles adamant about safeguarding the serene isolation of Locke. They outnumber Chinese residents by four or five to one. "We don't want development," she says.

Chu counters that development would benefit Locke by bringing modern sewer and water services to a town that is still pretty primitive. The traffic would boost Locke businesses, he adds, plus provide jobs that might lure back some former residents.

"Locke was really rundown when we bought it," Chu says. "Most of the businesses were abandoned, like a ghost town. We want to revive Locke. But it has to change. Locke used to be a prosperous town with 500-1,000 people. Nowadays the gambling and saloons are gone. Only 80 people live in Locke. It is a different town."

Indeed, the remaining Chinese residents agree that something drastic must be done to prevent Locke from disappearing from the Delta altogether.

"It's a very precious town, you know. God-awful precious," says Chinese-American Carol Hall. "But in 20 years, it won't be Locke anymore. It's sad knowing that. You see five gentlemen on a bench one day, then three, two, one..."

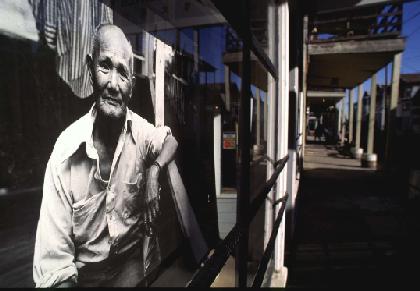

And they are almost all gone now. A few elderly residents still tend

the choy and melons in backyard gardens, fishing in sloughs, counting the

winters. Backs may be bent and legs bowed, but memories of old Locke remain vivid.

gardens, fishing in sloughs, counting the

winters. Backs may be bent and legs bowed, but memories of old Locke remain vivid.

"In the 1950s, the gambling really kept people going," says Mon Chan, 68. "This place was active, now it's dying." Yet he suffers no nostalgia. "A little culture is nice, but in the old days, nobody cared about those things, like the environment."

Lucy Chan, 64, tells how she raised five children above the town's grocery store. "When we lived here, it was all Chinese. There were more than 400 in the 1950s. Now only a handful are left, but you can't blame them for moving away."

Ping Lee, son of one of the town's founders, was born in Locke in 1917. He's among many homeboys who live nearby. Lee runs the Big Store a few miles down the road in Walnut Grove, but is considered "mayor of Locke." The town is unincorporated and has no elected officials.

"Locke's heyday was in the 1920s," he recalls fondly. "Even the Depression was good as a kid. We played games and grew up just like if we were in China."

Depending on the source, the origins of Locke could be placed to any date between 1900-1920. Chinese had been living along the Delta since the 1860s, but always in crowded ghettos.

A disastrous fire in the Chinatown in nearby Walnut Grove prompted Ping's father, Lee Bing, and a few friends to approach George, Clay and Lloyd Locke about leasing some land from the brothers. The Alien Land Act, a result of the rampant racial tension in the United States, kept Asians from owning land.

A deal was struck to clear nine acres of orchard for the new town in 1916. Bing financed the construction of nine buildings that year, joining three existing Chinese businesses that served the large group of laborers already living in the area.

Chinese in the Delta were mostly from the Sze Yap region of China, but the founders of Locke were from Zhongshan, north of Macau. They spoke a common language and soon established social societies that mirrored those they left behind in China.

Most of the Delta's Chinese residents were men. They fled the fields, where they worked six-days weekly, to enjoy the vices of Locke, a Chinese version of Dodge City. Pork sold for 10 cents a pound; an hour of pleasure for slightly more. Gambling boomed along with the illegal peddling of alcohol in the Prohibition period, 1920-33. But, for all the rowdy western touches, Locke was essentially a Chinese town with strong ties to the mainland.

Among the town's major societies were the Jan Ying, mainly Chung-san people, and the Quo Min Tong, representing the Nationalist Party of China. The Chee Kung Tong were followers of Dr. Sun Yat-sen. One of the region's more sordid scandals concerns the raising of funds to buy a dozen planes for Sun Yat-sen, which were burned at the boat dock by a rival gang.

Yet the community was cohesive and self-supportive. Joe Shoong, millionaire founder of a chain of dry goods stores, donated the money for the town's first Chinese school in 1926. The gambling houses outfitted the school, as well as a Baptist Mission.

The three blocks of Locke retain many reminders of the golden days. Faded Chinese calligraphy can be viewed on the sides of stores like the deli, which offers Budweiser along with sticky buns, and almond cookies as well as Haegen dazs ice cream.

Pauline Fok advertises an acupuncture clinic on the same main street where a 1920s gas pump sits in front of the old Foon Hop casino. The Yuen Chong Market, known as the "Flourishing Source Market" or "Horn of Plenty," survives as a general store.

Gone is Owyang Tin Git, a drygoods store built in 1916, that later saw service as a grocery, ice cream parlor and part-time lottery stall. However, Chint Owyang, 92, remains in residence. Her daughter brings groceries on regular visits, but wonders how long her mother, or Locke itself, can survive.

"Locke used to be all Chinese," she says, "but they go away, like me, all of them, one by one. Maybe some will come back, but it's hard to imagine what for."

Lee would like to see more state involvement in mapping out a plan to not only protect the town, but provide for prosperity. "Maybe the solution is to make this a kind of park, so you can finance the improvements, but control development."

However, he is far from optimistic. "There was a period of time, about 12 years ago, when the state was talking about taking over. Then, they ran out of money. Lots of people have had big plans for Locke, but it's all been talk. Time is running out."

Solutions aren't simple. While Asian City owns the land under Locke and surrounding orchards, the actual buildings are rented from a battery of outside interests. The landlords include clubs as far away as San Francisco and some Sacramento friends who bought the Locke buildings as a lark and are unlikely to invest much in improvements given the minimal return of rent.

Constraints imposed by the listing in the National Registry also restrict renovation that is inconsistent with the historical qualities of the town. Chu has already run into problems over basic repairs. Even the color of paint is controlled.

Doing nothing may well condemn Locke to destruction, worries Ping. "No one wants Locke. The cost is high and no value there. The potential is there, but maybe it's not enough."

Chu says his company is committed. "Locke is a good mixture of old and new. It's a genuine antique. That's the value of the town. Like an antique vase, you treasure it for the antique value." He adds, "We want to utilize that antique value."

However, outside experts worry whether any effort to embrace the attributes of the town will destroy it. James Motlow, in the introduction to his book about Locke, "Bitter Melon," writes of the battery of proposals for preservation: "Locke would cease to be a Chinese community and become a museum of one instead."

Local farmer Bill Shelton, who wrote "Bailing Dust" about his boyhood on the river, says Locke is already protected. By ghosts.

Indeed, several fires have spared the 30 tinder-dry buildings that remain in Locke. Shelton says spirits from the old opium dens still protect the town from "the white man's world."

As the Delta days pass in a Tule haze and more of the town's old residents and buildings fall victim to the toll of time, Lee worries that Locke may be left only with the spirits, sweeping through the wild streets of the last Chinese town in America.

"I just don't see much of a future for Locke as a Chinatown, not unless those new houses are taken by Chinese," he say sadly. "If you're going to have a Chinatown, you need Chinese.".

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who is based in Hong Kong, roaming around the world in search of good yarns. He first wrote about Locke while working as a reporter in Sacramento in the mid-1980s. This story appeared in various American Express magazines in Asia, and also in the South China Morning Post.

The photos on this page, and nearly all the scanning for this web site, are the work of David Paul Morris, an American photographer who often travels with Ron Gluckman. For other examples of Mr Morris' work, turn to the China Beach, Melbourne Comedy, Hung Le, Coober Pedy, the Urge to Merge, The Other Hong Kong and Spears of Death.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]