The Other Hong Kong

The world watched the countdown to the Chinese takeover of Hong Kong in 1997 with concerns about human rights and rule of law. Across the Pearl River, the watch continues as Hong Kong's sister colony of Macau awaits its fate as the next dish in the great Chinese takeaway

By Ron Gluckman / Macau

T

IME IS TICKING TOWARDS THE MIDNIGHT HOUR for Europe's last colony in China. Yet, instead of panic, the final hours are filled with a mad pursuit of profit.Construction is underway everywhere around the tiny outpost along the Pearl River. There’s a brand-new international airport, a container port, massive landfill projects that will add office buildings, hotels and tens of thousands of new housing units, and towering bridges linking them all together.

Business isn’t the only thing booming in this tiny European enclave at the

southern tip of the Middle Kingdom. Defying the doomsayers, optimism is on a high too as

the colony prepares for its rapidly-approaching reversion to Chinese rule. At least,

that’s the case in Macau.

Business isn’t the only thing booming in this tiny European enclave at the

southern tip of the Middle Kingdom. Defying the doomsayers, optimism is on a high too as

the colony prepares for its rapidly-approaching reversion to Chinese rule. At least,

that’s the case in Macau.

While the world watches with trepidation the ongoing battles over the fate of Hong Kong in the countdown until the Chinese takeover on July 1, just an hour by jetfoil across the Pearl River, the older Portuguese colony of Macau is making breathtaking progress before its expiration date at the end of 1999.

Signs of new affluence abound in Europe’s first gateway to the Far East, where 450,000 people (about 7.5 percent of Hong Kong’s population of six million) are crammed into Macau’s seven square kilometers and two smaller islands, Taipa and Coloane.

"The race is on," says one local businessman, referring to the pace of development rather than Macau’s infamous greyhound races. "China is around the corner, but until then," he adds, "there’s money to be made."

Such sentiments seem incongruous in Macau, a sleepy little backwater for over a century. Settled by Portuguese traders in the mid-1500s, Macau was part of a string of flourishing Portuguese trading posts that once stretched across Asia from India all the way to Japan. But the West’s first foothold in the Far East was supplanted soon after Hong Kong was established in the mid-19th Century. Since then, Macau has lingered in the shadow of the larger British colony, a mere 40 miles away.

Both colonies now grapple with a multitude of adjustments enroute to a future under

rather than alongside China. Yet Macau seems to have sidestepped the strife befalling its

colonial cousin and has taken a fast track to new fortune.

Both colonies now grapple with a multitude of adjustments enroute to a future under

rather than alongside China. Yet Macau seems to have sidestepped the strife befalling its

colonial cousin and has taken a fast track to new fortune.

Macau’s first international airport opened in 1996 at a cost of US$1 billion. It was finished in only four years - less time than it has taken China and Britain to hammer out an agreement for the Hong Kong’s new airport, which won’t even be open when the British flag is lowered at midnight on June 30, 1997. (The airport opened in 1998).

Likewise, Macau’s new container port was already approaching capacity while Britain was still battling Beijing over a similar facility planned years previously for Hong Kong. China has also approved massive landfill projects that will increase by 20-30 percent Macau’s previously limited landmass, all designed to enrich the colony in the run up to its revision to Chinese rule in December 1999.

Nor are the contrasts strictly of a commercial nature. Beijing condemned last-minute democratic liberalization in Hong Kong, shaking worldwide confidence in the British colony by dissolving the legislature the day it took over Hong Kong. In contrast, elections the previous September went ahead without a hitch in Macau, where a record turnout of voters and candidates guarantee the smooth function of government into the next century.

Whether or not this has been intended as a slap in the face to Hong Kong, as is widely held on both sides of the Pearl River, hardly matters to Macau. After a slumber of several centuries, no one is questioning the unexpected millennium-ending renaissance. Residents believe they are reaping the rewards from a less confrontational style that Portugal has followed for centuries.

"There is no need to suggest that Macau is on the right track and Hong Kong is on the wrong one," says Joao Mira Gomes, Portugal’s Diplomatic Advisor to the Governor of Macau. "What we do say is that Macau is on the right track."

Like many in Macau, he emphasizes the long record of positive relations with Beijing, paying special attention to the mid-70s, when Portugal disposed of its colonies from Asia to Africa. Locals say Lisbon offered Macau outright to the Chinese, demonstrating a lack of colonial design on the region. Instead, the colony was redefined as a Chinese territory under Portuguese administration.

"We have always enjoyed good relations with China, right from the start,"

says Gomes. While Hong Kong was wrestled from China by Britain in the Opium Wars, he

notes, "We never fought the Chinese, we never invaded China."

"We have always enjoyed good relations with China, right from the start,"

says Gomes. While Hong Kong was wrestled from China by Britain in the Opium Wars, he

notes, "We never fought the Chinese, we never invaded China."

Still, Macau has its own growing pains to contend with. While per capita GDP is up to US$16,000, unemployment has also risen, from three percent in recent years to 4.7 percent. The construction boom has created enormous ghost neighborhoods but few buyers. Officials say there are 30,000 vacant apartments, but real estate agents say the figure is probably twice as high.

Even more worrying is what role Macau can play in southern China, which has been growing at double-digit rates. Hong Kong will surely continue as an international trading hub, but other Chinese cities - Zuhai and Guangzhou, north of Macau and Hong Kong - already offer the population base, industry and infrastructure to lay claim as the Pearl River’s other major centers of commerce.

"Macau depends on tourism and gambling. It’s the Las Vegas of Asia, and that’s what it will be in the future," says Hong Kong financial guru Mark Faber. "It’s just too small, too limited for anything else."

Nor is Macau helped by its reputation for corruption and crime. Show girls may be an inherent part of the gambling glitz, but Chinese gangland slayings have also become commonplace in Macau over the years. Asian mobs are notoriously active in the enclave; likewise call girls from Thailand, China, the Philippines and Russia. A huge counterfeiting ring was traced to a North Korean gang based in Macau. And last summer, the mayor of Jiangzhou, across the border in China, was executed for squandering US$1.7 million in public funds during dozens of gambling excursions in Macau. Such publicity only further solidifies Macau’s nefarious role as the Sin City of South China.

"No one really looks at Macau seriously," adds an analyst at Lehman Brothers

in Hong Kong. He says reports of rampant corruption and inside deals puts off investors,

and opportunities are minimal in Macau. "It’s too small, too closed a market and

suspect. Macau doesn’t even come up on the radar screen."

"No one really looks at Macau seriously," adds an analyst at Lehman Brothers

in Hong Kong. He says reports of rampant corruption and inside deals puts off investors,

and opportunities are minimal in Macau. "It’s too small, too closed a market and

suspect. Macau doesn’t even come up on the radar screen."

Besides gambling - which brings in about half of Macau government revenues - the economy is dominated by textiles and manufacturing. But much industry has merely moved over from Hong Kong, mainly to benefit from European export quotas. Those preferential trade benefits will soon end, leaving Macau to find a new niche after five centuries as a bridge between Asia and the West.

Tourism holds great potential. Most of Macau’s eight million annual visitors come for the gambling, to be sure, but the colony has shown a keen determination to expand its tourism portfolio. New additions include wine and maritime museums and an innovative Grand Prix Museum that offers simulator rides along the route of the enclave’s famous yearly road rally. And US$13 million has been earmarked for an underground historical museum beneath the old city walls. Macau recently renovated its European central square, creating a cobblestone pedestrian mall, surrounded by glorious colonnaded stone and brick buildings.

"Our heritage is what sets us apart," says Joao Manuel Amorim, director of

the Fundacao Oriente Delegacao de Macau. Charged with promoting cultural links to Portugal

and the past, the agency spends over US$30 million annually on a mixture of education and

cultural programs, and renovation of Macau’s magnificent colonial edifices.

"Our heritage is what sets us apart," says Joao Manuel Amorim, director of

the Fundacao Oriente Delegacao de Macau. Charged with promoting cultural links to Portugal

and the past, the agency spends over US$30 million annually on a mixture of education and

cultural programs, and renovation of Macau’s magnificent colonial edifices.

Daytrippers from Hong Kong - 80 percent of Macau’s visitors - have long relished the delightful difference between the two colonies. Where Hong Kong is all bustle and brash, Macau is lazy, in a Latin way. Hong Kong is overrun with high rises, and its famous Fragrant Harbor has become polluted with the poisons of development. Hong Kong neighborhoods echo with the noise of urban redevelopment, while its cluttered streets attest to the territory’s claim as the world capital of luxury cars.

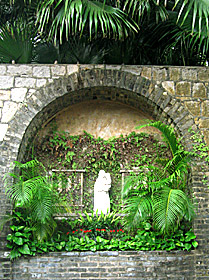

In contrast, Macau boasts Mediterranean-style cafes and alleys, along with Chinese palm readers outside parks where ancient men puff on pipes while being serenaded by caged songbirds hanging in the trees.

This evocative blend of the old West and the Orient has historically been Macau’s charm - and downfall. For decades, investors have forsaken Macau for this very reason, because its been stuck in the past. Macau was the site of the first western university and hospital in Asia, as well as the place where the world’s two superpowers - China and the United States - signed their first treaty. But all these glories came centuries ago.

However, Macau need not mourn its lack of development anymore. In fact, the tortoise’s pace followed by the Portuguese may bring Macau profit from its past.

"It’s sheer good fortune that development in Macau has been so slow," says Shann Davies, author of six books about Macau. "Gambling may be the main attraction of the masses, but Macau’s heritage is what makes it a destination."

Adds Gary Ngai Mei Cheong, vice president of the Cultural Institute of Macau:

"We’re lucky, we have the opportunity to preserve our history and our unique

heritage. We still have our temples, churches and old buildings. We’re much better

off than Hong Kong, which has become a jungle of concrete."

Adds Gary Ngai Mei Cheong, vice president of the Cultural Institute of Macau:

"We’re lucky, we have the opportunity to preserve our history and our unique

heritage. We still have our temples, churches and old buildings. We’re much better

off than Hong Kong, which has become a jungle of concrete."

He says these qualities are essential to Macau’s survival as a small, but distinct enclave within the world’s largest nation. "Our cultural identity is extremely important. If we lose our culture, after 1999," he warns, "we’ll become just an appendix to Zuhai, our Chinese neighbor."

Adds Gomes: "Macau has unique Portuguese and Chinese influences, but it is the Portuguese that makes Macau unique. We’re not neo-colonialists by any means, but we do want to emphasize these elements. That’s what Macau needs to be autonomous after 1999."

Since passing its first preservation statues in 1976, Macau has classified scores of protected sites. Most were government buildings or churches, but the codes have been broadened over the years to include monuments, greenbelts, even entire neighborhoods. While preservation efforts failed to save some historical relics, like a clutter of old buildings around the Chinese bazaar, there are many success stories. These include the neo-classical Dom Pedro V Theatre, where a version of "Romeo and Juliet" was recently staged in Portuguese, and St. Raphael’s, the first European hospital in Asia. The latter building, now occupied by Macau’s Monetary Authority, will house the first Portuguese embassy after 1999.

"It was in ruins when we started the restoration," says a proud Amorim, whose

foundation is housed in another valuable relic, the 200-year-old Casa Gardens, which was

the headquarters of Britain’s East India Company before the founding of Hong Kong.

American President Grant is among the guests who have walked Casa Gardens’ lush

grounds. No public money is used to maintain the building, or support the

foundation’s endeavors. Instead, funding comes entirely from a 1.6 percent duty

imposed on Macau’s gambling revenues.

"It was in ruins when we started the restoration," says a proud Amorim, whose

foundation is housed in another valuable relic, the 200-year-old Casa Gardens, which was

the headquarters of Britain’s East India Company before the founding of Hong Kong.

American President Grant is among the guests who have walked Casa Gardens’ lush

grounds. No public money is used to maintain the building, or support the

foundation’s endeavors. Instead, funding comes entirely from a 1.6 percent duty

imposed on Macau’s gambling revenues.

This isn’t to suggest that the private sector has been slow to reinvest in Macau’s past. Quite the contrary. Many scoffed when Hong Kong and Macau investors announced a US$6 million scheme to restore a 125-year-old mansion-turned-guesthouse called the Boa Vista (Good View). Critics said the hotel, scaled back from 32 to only eight spacious Old World-style suites, would never turn a profit.

"But we’re getting close," says Andrew Hirst, general manager of both the Mandarin Hotel and its magnificent sister-hotel, the re-launched Bela Vista. The latter is still losing money, but has attracted marvelous international attention to Macau. Expression, a magazine for American Express cardholders around Asia, recently put the Bela Vista on its list of the ten grand old hotels of Asia.

Like other hoteliers, Hirst awaits a tourism boost from the opening of the airport, offering direct links to Europe for the first time. So far, though, business has been meager. Most travelers use Macau as a gateway between Taiwan and China, which have no direct air connections.

Yet hoteliers in Macau are enthusiastic about the prospect of selling Macau as a bargain base for daytrips to Hong Kong, instead of the other way around. One hotelier jokes about a once-in-a-lifetime package that could begin in Hong Kong before June 30, 1997, the last day of British rule in Hong Kong, continue with a ferry ride to Macau, and end with a flight home from the new airport. But attitudes about Hong Kong are no joke here, and anxiety is high.

"At least we can watch and wait to see how the Chinese muck things up in Hong Kong," says an English pensioner, while guzzling beers at the Billabong, Macau’s Australian pub.

The bar’s clientele is mainly European expatriates who have fled the crowds and expense of Hong Kong, purported to be the world’s priciest business city, for the peaceful and affordable lifestyle of Macau. The barmaid is Filipino, as are many hotel and restaurant workers around town. These recent newcomers are adding a cosmopolitan complexion to what has essentially been a closed society of three classes for centuries: Portuguese, Chinese and Macanese.

The latter are of mixed Chinese and Portuguese descent, but many Macanese have intermarried for generations, forming a distinct class that does not exist in Hong Kong. Believed to number about 30,000, Macanese fill most management positions in Macau. They are fluent in Portuguese and Cantonese, the language of Southern China, but few read Chinese or speak Mandarin, the main Chinese language. They have the most at risk when English supplants Portuguese as the trading language of the future. Many Macanese are also Catholic, a relic of the Portuguese past. Religion is suppressed in communist China.

Like Hong Kong, Macau has an agreement with China that guarantees the same laws and

system of rule will remain in place for 50 years. But the battles across the river in Hong

Kong, and China’s public denouncement of many of those guarantees has generated

jitters in Macau.

Like Hong Kong, Macau has an agreement with China that guarantees the same laws and

system of rule will remain in place for 50 years. But the battles across the river in Hong

Kong, and China’s public denouncement of many of those guarantees has generated

jitters in Macau.

"Of course, we are all watching with great interest what happens in Hong Kong," says Cheong. "In that way, we are lucky, because we have two years more to prepare ourselves." But, he notes, Macau has more critical questions of mass. Over half of the residents of Macau were born in China, and nearly half have lived in Macau for 15 years or less. "Hong Kong is bigger. If 100,000 new immigrants come, that’s nothing to Hong Kong. But for us, it would be 25 percent of our population. Macau is far more vulnerable."

Which is why few take solace in the sudden resurgence of the colony’s European heritage, which they discount as too little and too late to spare Macau its likely assimilation into the Chinese land mass. "It’s like the man who only buys flowers for his lover as she’s packing her things to leave," notes one official.

"We can’t do it all, and we certainly can’t do in a few years what we haven’t done in 450 years," admits Amorim. "But more is at stake than only Macau. There’s the psychological factor, too. This is the end of an empire for Portugal. In Macau, we have the chance to write a nice ending to what once was a grand empire."

Still, few believe Beijing will relinquish much control over the script, which will, in any case, likely be just a sequel to the big show, this summer in Hong Kong. "To say that all eyes are on Hong Kong, is an understatement of the highest order," says a British business consultant in Macau. "We are watching, waiting and hoping.

"But mostly in Macau," he says, sipping a pint, "we are praying."

Ron Gluckman is an American journalist who was based for a decade in Hong Kong (then in Beijing and Bangkok), traveling widely around the Asian region for a variety of publications, including Manager Magazine, which ran this piece in 1997. Similar stories on Macau by Ron Gluckman also ran in Asiaweek, and were carried by MSNBC.

For another story on Macau's transition to Chinese rule, please click upon the Godfather of Macau. To see a related story on China's takeover of Hong Kong, please see the Man who beat Beijing.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]