LIFE IN PARADISE

By train through the Hermit Kingdom, our reporter dodges officials and sifts through the lies and secrecy on track to follow his family's Great Escape

By Ron Gluckman / North Korea

M

Y FIRST GLIMPSE OF THE LAND OF LIES comes just after Dandong, when the train climbs the bridge over the Yalu River, then plunges forward into the Great Unknown, the world's last refuge of secrecy and deception. China recedes back along the tracks, and up ahead looms a huge bronze statue of the Great Leader, Kim Il Sung. Longest reigning dictator on Earth, Kim has run North Korea like a police state since

1945. His statue towers over the trees, and it's a fitting welcome to the weird world he

has cast in his own demented image, for Kim is everywhere.

Longest reigning dictator on Earth, Kim has run North Korea like a police state since

1945. His statue towers over the trees, and it's a fitting welcome to the weird world he

has cast in his own demented image, for Kim is everywhere.

As we pull into the drab railway station in the border town of Sinuiju, an enormous huge mural depicting the heroic deeds of the Great Leader dominates the view. Both monuments will be repeated endlessly in every city and town I pass through during my tour of North Korea (during the summer of 1991).

Yet the first view of the Great Ego still thrills. After more than a year of effort at obtaining entry permits for the Hermit Kingdom, I have finally penetrated the paradoxical, paranoid paradise of North Korea. My companion, guidebook author Robert Storey, grabs my hand in a victory shake. "We made it, we're inside North Korea," I mutter, as we share a sweet conspiratorial smile.

For weeks we have kept our fingers crossed, prepared for new complications every step of the way. Visa applications have repeatedly been rejected, six times over in my case. Even after obtaining a rare and very expensive visa, the train tickets we paid for never appeared in Beijing. North Korean officials at the embassy in China were not sympathetic, clearly piqued to find that two Americans dismissed earlier at the same office had obtained visas elsewhere. Determined to proceed, we buy our own black-market tickets in Beijing, paying double the previously-agreed price.

Indeed, nobody was more surprised than I that day Robert called from Macau, the (until the end of 1999) Portuguese colony across the Pearl River from Hong Kong, where North Korea has long maintained a diplomatic corps involved in gambling, gun running, smuggling and counterfeiting. The officials also occasionally dealt in visas; and we managed to elicit a rare pair.

Even now, on the train with tickets in hand, I suspect some last-minute hitch will prevent us from crossing over the Yalu River into the ancient empire of Koryo, known as the land of Morning Calm until war quelled the serenity and split the place in two for 40 years. Paranoid? Perhaps. When I discover a stray business card that had eluded an earlier search - it's my bookmark - I quickly hop out of bunk and take it to the train bathroom, where it burns and the ashes are washed out the toilet in the floor.

Journalists aren't welcome here, so we're traveling as English teachers. All outsiders are considered to be cultural invaders in this wayward republic. Therefore, I am careful not to be seen taking notes. I jot down impressions inside a bathroom stall, keeping my diary in a tiny notepad, tucked into a hip pouch along with rolls of exposed film. I wear this even while asleep.

All this sneaking about seems suitable here, in an atmosphere of scrutiny and suspicion. And, if the truth be known, the North Koreans have every reason to suspect us. We have indeed come to report upon the last bastion of hard-line socialism - in a sense, to spy upon them. But, that is always the case with reporting. Yet, in over a decade of snooping, from Belfast to Burma, I have never felt so oppressed by officialdom, nor so vulnerable to the vagaries of a paranoid population.

Storey is on assignment for

Lonely Planet,

which produces the Shoestring and Survival Kit series of books that have become bibles of

the backpack circuit. I intend to file stories on any subject that can be adequately

researched within the tight limitations of this restrictive society. I'm posing as a train

buff, to cloud the true purpose of my travels. My main goal is to simply ride the rails

from Shenyang all the way to the South Korean border, the most militarized region on

Earth. The 1.5 million armed Koreans glaring at each other across the expanse of barbed

wire and concrete concern me no more than the nuclear weapons factory western nations

believe North Korea is constructing in Yongbyon. Good stories, both, but this time the

journey itself is the tale I fancy telling.

Storey is on assignment for

Lonely Planet,

which produces the Shoestring and Survival Kit series of books that have become bibles of

the backpack circuit. I intend to file stories on any subject that can be adequately

researched within the tight limitations of this restrictive society. I'm posing as a train

buff, to cloud the true purpose of my travels. My main goal is to simply ride the rails

from Shenyang all the way to the South Korean border, the most militarized region on

Earth. The 1.5 million armed Koreans glaring at each other across the expanse of barbed

wire and concrete concern me no more than the nuclear weapons factory western nations

believe North Korea is constructing in Yongbyon. Good stories, both, but this time the

journey itself is the tale I fancy telling.

Half a century ago, my father, then a child, and his parents rode these same rails to escape from Hitler and the Nazis. They boarded a train in Berlin, came across Poland and the USSR, down through Manchuria, to the southernmost tip of Korea, then the Japanese colony of Chosen. A ferry to Shimonoseki connected to a ship that took them across the Pacific, to the safety of America, where they would survive World War II. Most of our relatives were not so lucky. About 2,000 German Jews eluded the Gestapo by this route, which was open for a scant six weeks. My family caught one of the last trains out in late 1940.

During a year of fellowship at Oxford University, I had prepared for retracing the great escape, but did it in a more leisurely fashion. My grandparents had moved the family across two continents in three weeks. I spent over a year, roaming around East Europe, visiting places familiar to me only from family history. I stopped at our former wood furniture factory in Breslau, now Wroclaw, Poland, and checked concentration camp records for the names of relatives. By the time I arrived in North Korea, I had already logged 11,000 kilometers across Siberia and through China. And, I had waited in Hong Kong for seven months, plotting plans to retrace the rail journey through the Hermit Kingdom.

Still ahead is the trip down through South Korea, the ferry to Japan, and a long crossing of the Pacific in a cold container ship. The company that shipped my family to America is still operating, but unwilling to put me on board. Maritime codes (then, and since the 1960s) prohibit passengers on Japanese cargo ships and few foreign carriers would even answer my pleas, an eerie reminder of the deaf ears turned to Holocaust victims. But so far, nothing has compared to the difficulties covering the few hundred miles of track through North Korea.

"You are Americans?" asks an Indian diplomat, who has been sharing our rail car. For hours, we have chatted with the diplomat and his wife, about travel and language and curries, everything imaginable except our telltale accents. Neither has been bold enough to broach the subject, until we do. Then, they pour out their feelings of amazement. "Yes, I've been very surprised, I must say, when you mentioned that you had visas," the wife says. "It's usually not possible at all for Americans. You are most lucky."

They have been stationed in Pyongyang for two years, so we bombard them with questions. They have little to reveal, chiefly because they are confined to a radius of 40 kilometers from the embassy housing estate unless they have permission to go further from the Foreign Ministry. They never visited the homes of North Koreans. "Not even our own girl, who cleans our house," the wife says. "She's so nice and friendly in the house, but if we see her on the street, she won't smile, she won't even wave to us."

Visitors are rare to a country desperate for foreign currency but fearful of the consequences. We are the only tourists on the entire train. The remaining passengers are diplomats, save for a family of Russians. He is a reporter for Pravda. As we pull into Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea, his pretty wife predicts: "You will be surprised." When I ask her meaning, she simply shakes her head and repeats, "You will be surprised."

We are met by a car and driver. Our guide, Li Yong Bom, hustles us through the comfortable foreigner's waiting room. There are a dozen padded chairs and, needless to say, a portrait of Kim Il Sung overhead. A glass case displays a selection of books and magazines in English, French, German, Spanish, Russian and Arabic. All extol Sung, except the few that focus upon his son and self-designated successor, Kim Jong Il. My favorite booklet is titled: "North Korea, An Earthly Paradise For the People."

Mounted in the hallway are a dozen photographs showing injustices to the North Koreans perpetuated by American and South Korean forces. We saw the same photographs in Shinuiju and see them again in every other railway station. Americans are "imperialists," "aggressors" or "hooligans;" South Koreans are "stooges" and "puppet police."

Yet the first thing I notice in our hotel is the wide array of western goods in the tourist shop. There are cameras from Japan, canned milk, chocolate and coffee from America, whiskey from Scotland, brandy from France, soda from England and Australia. Everything is overpriced, but I stock up on American cigarettes. In a country that claims no corruption, doors tend to open easier when the path is greased by Marlboros.

The streets of the capital are as wide and clean as the lush green Korean countryside. And just as empty. That's the thing that always shocks visitors. "There are no cars, no traffic," the Indian diplomat tells us. "The streets are empty. Pyongyang has no crime. And it must be the cleanest city in the whole world."

It's also pretty in its way, with tree-lined boulevards and huge squares ornamented with fountains and statues. A river runs through the center of the city and along its banks are a series of beautiful parks. The disturbing aspect of all this scenery, though, is that you never see anyone enjoying it. The parks are empty, the theaters vacant, the stores all seem to be closed. Eeriest of all is the 150,000-seat stadium Pyongyang constructed in a failed bid for a portion of the 1988 Olympics. A stadium filled with drunken sports fans can be loud and chaotic, but an empty bowl of yellow benches is downright depressing.

Movement in Pyongyang is strictly controlled, as is residency itself. "Before we

arrived two years ago," our Indian friend tells us, "there used to be no

disabled and hardly any old people. You couldn't have gray hair." Pregnant women were

also banned from Pyongyang, but these rules have been relaxed.

Movement in Pyongyang is strictly controlled, as is residency itself. "Before we

arrived two years ago," our Indian friend tells us, "there used to be no

disabled and hardly any old people. You couldn't have gray hair." Pregnant women were

also banned from Pyongyang, but these rules have been relaxed.

The Koryo Hotel is the finest place in Pyongyang and it's an impressive sight, two twin towers rising 47 stories. Both are topped with revolving restaurants, but only one is open. There's not much demand, since the 500-room hotel has only 35 guests during our stay. Not much else is open in Pyongyang or anywhere in North Korea. The most famous building in the country has to be the Ryugyong Hotel. At 105 stories, it's one story taller than a hotel constructed by a South Korean firm in Singapore. The pyramid-shaped Ryugyong is said to contain a hospital, bowling alleys, a cinema and 3,000 hotel rooms. Nobody knows when it will be finished. Nobody can even say how long it's been under construction.

Subway stations in Pyongyang are in the Moscow mold of proletarian luxury, with polished marble floors, arched white pillars and sparkling chandeliers. Among the many murals of Kim Il Sung is one showing him and his son in a mountain setting. All the scenery is red or violet. Mars comes quickly to mind.

Above ground, too, Pyongyang has the same unworldly quality with its dazzling fountains surrounded by park benches with nobody upon them, ghost trolleys that run sleekly through silent streets, empty save for the state fleet of Mercedes, reportedly the largest in the world, conveying top cadres to furtive ministries. Only the department stores are filled with people, but nobody seems to be allowed to purchase anything. I stand outside one store for a full hour and not a single person leaves with a bag.

Pyongyang would make a great setting for a science fiction film.

The place is already filled with props. In the center rises the Arch of Triumph, taller

than the original in Paris - which isn't mentioned in Pyongyang. I focus my camera for

three minutes at midday upon the Arc before a car passes through.

Pyongyang would make a great setting for a science fiction film.

The place is already filled with props. In the center rises the Arch of Triumph, taller

than the original in Paris - which isn't mentioned in Pyongyang. I focus my camera for

three minutes at midday upon the Arc before a car passes through.

The train to Kaesong leaves at midnight and arrives at dawn in the ancient capital of the Koryo empire. Kaesong is the prettiest city in Korea and among the loveliest in all Asia. Kaesong is winding alleys, old homes with curved tile roofs, gardens and guest houses with bamboo bed mats. The serenity of this sleepy, peaceful city gives way to the greatest concentration of military muscle on the planet. The train tracks used to continue south to Pusan, but now we ride a car 10 miles to the peace village of Panmunjom, where the poorly named Reunification Highway ends in barbed wire.

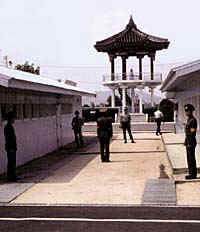

Panmunjom is surely the strangest tourist trap on Earth. Visitors sit at the peace conference table, a line running right through the room. While guards from the South Korean side peer through windows, North Korean officers give a briefing on the outrages of the western imperialists. A gift shop sells separatist souvenirs.

Then the cars leave for a ride through the hilly countryside. A battery of tripod-mounted binoculars await at a viewing site. They focus upon a concrete wall curving over the distant hills. "That's the wall built by the Americans to divide our country."

Actually, according to a western diplomat, it's a tank barrier two kilometers wide built in the 1970s to prevent against another North Korean sneak attack. "The North Koreans never mentioned it until the Berlin Wall fell," she says. "Then, they cried Wall." One Korean returning to his homeland from Germany sadly comments on the presence of so many soldiers. "They could be my relatives," he says. "Why must relatives be divided, pointing guns. Even in Germany it's ended.

"It must end here."

Koreans from all over the world pay US$150 a day to tour their ancestral home. They are

taken to temples, into the misty mountains, and everywhere wined and dined in a style that

is otherwise unimaginable in North Korea. "This is more meat than they see in a

year," one Korean from Japan says at mealtime. "They are trying to pretend there

is abundance, but we know they have not even enough rice to feed the people."

Koreans from all over the world pay US$150 a day to tour their ancestral home. They are

taken to temples, into the misty mountains, and everywhere wined and dined in a style that

is otherwise unimaginable in North Korea. "This is more meat than they see in a

year," one Korean from Japan says at mealtime. "They are trying to pretend there

is abundance, but we know they have not even enough rice to feed the people."

Indeed, diplomats and reporters confirm rumors of years of rice crop failures. Oleg Polovko, on assignment for Russian news agency Tass, confides: "We hear of rice shortages, but there is no way to know for sure. We cannot call any of the ministers. We cannot go to the farms in the country. The only news they give out is the good news of the government. It's all lies."

One truth is the need for foreign currency. With the Soviet Union in recession, North Korea is deprived of the patronage that provided most of the nation's energy and equipment needs. Turning to tourism, even in moderation, has helped.

Many visitors come from Japan and several join us on the train back to Pyongyang. North Korea is courting yen. Listening to two of them chat in Japanese, I think of my father, who still remembers a few words he learned from Japanese soldiers returning from the front when he was a child refugee.

"When I was on that train, during the war," he says by phone upon my return to Hong Kong, "it was only soldiers and us. And the windows were blacked out so we couldn't see anything."

Half a century later, little has changed. The train windows open, but North Korea remains closed to the world.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who first came to Hong Kong in 1990, while following his family's escape route from the Nazis in late 1940. He eventually settled in Hong Kong, his base for covering a wide region of Asia for such publications as Time, Newsweek, the Wall Street Journal, Discovery and Mode. He went to North Korea after obtaining a rare visa in the summer of 1991, filing stories for numerous publications including the Washington Post, South China Morning Post, the Peak, and Asiaweek, which ran this piece in September 1991. For other stories on North Korea, click on Cinema Stupido, On the Border, or Last Tango in the People's Paradise

Also, look for Ron's package on North Korean tourism in Time Magazine in summer 2001.

And Ron's coverage from North Korea during another visit in Sept 2004 to crash the Pyongyang Film Festival!

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]