Ritzy rooms with world's best views

The Ritz returned to Hong Kong with an iconic hotel, the world's tallest, atop the new International Commerce Centre in Kowloon. With mind-boggling views, the hotel, and building not only break records, but offer new advances as the skyscraper returns to a place that populated its presence across Asia, and signals that the quest to build ever taller continues unabated.

By Ron Gluckman/in Hong Kong

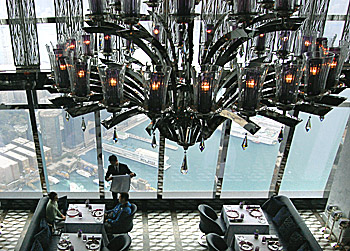

WITH THE RECENT OPENING IN HONG KONG of the Ritz Carlton on the upper floors of the International Commerce Centre, this city now boasts the world's highest hotel (with the highest pool). More important, the sleek ICC marks the return of the record-beating skyscraper to a city that helped spawn a global skyscraper race.

The Golden Age of the skyscraper began in 1930s Chicago and New York. Hong Kong was only the first city outside the U.S. with a skyscraper topping 1,000 feet—1989's Bank of China Tower—but it spurred a quest for the heavens that spread to cities across Asia and eventually to the Persian Gulf.

Experts believe the 108-story ICC, now

the fourth-tallest tower in the world, is a significant step towards the

supercity of the future, which will soar into the skies amid increasing

population pressures. Key to such towers is the integration of services and

infrastructure, particularly transportation.

Experts believe the 108-story ICC, now

the fourth-tallest tower in the world, is a significant step towards the

supercity of the future, which will soar into the skies amid increasing

population pressures. Key to such towers is the integration of services and

infrastructure, particularly transportation.

The 1,588-foot ICC—which houses the Asian headquarters of Morgan Stanley, Deutsche Bank and Credit Suisse—is set atop a transportation hub that connects the local subway, a 20-minute express train to the airport, and railways to China.

"The ICC is a wonderful example of linkage," says Paul Katz, architect of the ICC and many other supertall structures. Bankers can fly in from New York, hop onto the airport express and enter the ICC ready to conduct business on site before zipping upward on some of the world's fastest elevators to a king-size bed at the plush Ritz. "There are considerable savings in the amount of energy not wasted in moving these people around," Mr. Katz says.

Antony Wood, executive director of the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, which serves as the arbiter of tall-building records, adds: "These buildings are needed in high-density areas like China. The alternative is more sprawl, and nobody wants that."

"Traditionally, the economics of building taller than 70 to 80 stories start to break down as so much of the floor area is taken up by elevators [that] there is little space left to rent," says Ron Klemencic, president of Magnusson Klemencic Associates, an engineering firm involved in many skyscrapers. Taller buildings also tended to taper inwards, further reducing rentable space; the cost of moving materials and people also soars.

"Today," Mr. Klemencic continued, "staggering land values have driven developers to stack office, residential and hotel uses into a single tower, making the economics of going taller more palatable."

Recent innovations in supertall construction have helped increase the odds of profitability. The ICC utilized new, high-strength concrete that can be pumped upwards more than 1,640 feet. Previously that ceiling was just above 650 feet. The ICC also employs Hong Kong's first state of the art, "intelligent" destination-based double-decker elevators, which are controlled by computers for maximum efficiency as they serve two floors at the same time, reducing the need for extra shafts.

Another factor increasing the chances the ICC will turn a profit: Hong

Kong's sky-high office rents, which are among the world's highest. Many recent

towers have been erected in places with ample land, like Dubai, home of the

world's tallest tower, the Burj Khalifa. That

2,717-foot skyscraper may never break even. Hong Kong's largest developer, Sun

Hung Kai Properties, built the ICC on cheaper, reclaimed land on the Kowloon

Peninsula, across the harbor from the high-density Central District—but only 10

minutes away by subway.

Another factor increasing the chances the ICC will turn a profit: Hong

Kong's sky-high office rents, which are among the world's highest. Many recent

towers have been erected in places with ample land, like Dubai, home of the

world's tallest tower, the Burj Khalifa. That

2,717-foot skyscraper may never break even. Hong Kong's largest developer, Sun

Hung Kai Properties, built the ICC on cheaper, reclaimed land on the Kowloon

Peninsula, across the harbor from the high-density Central District—but only 10

minutes away by subway.

"There are no new buildings coming on line in Central. There is no more space," says K.W. Lo, Sun Hung Kai Real Estate's leasing general manager. He says the ICC, with more than 2.5 million square feet of office space, is now 97% rented, at prices less than half the cost of top-end Central offices.

The site also allowed for unusual innovation in construction. SHKP spent $1.7 million to erect a temporary tower adjacent to the site. With six work elevators, the tower hoisted construction materials better—and more cheaply—than any cranes.

Hong Kong's risk of typhoons prompted Mr. Katz, of Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates, to rethink the usual approach to sway in tall towers. Most skyscrapers utilize pendulums or dampers, designed to transfer the motion of the building to mitigation devices.

These can be enormous. Taipei 101, the world's second-tallest building, sports a massive 660-ton steel ball, suspended from the 92nd floor, that swings in full view of visitors. Hong Kong—with some of the world's highest concentration of tall buildings—often opted for rooftop water tanks that do double duty: They are designed to slosh around to mitigate the building sway, but can also be used in case of fires.

Instead,

Mr. Katz designed the entire ICC to provide wind buffers. Instead of meeting in

corners, the sides join in recessed notches. Its scaled surface—which gives the

building a dragon appearance beloved by Chinese—also breaks up wind force. "It's

like the opposite of an aircraft's wing," Mr. Katz explains. "It breaks up

lift."

Instead,

Mr. Katz designed the entire ICC to provide wind buffers. Instead of meeting in

corners, the sides join in recessed notches. Its scaled surface—which gives the

building a dragon appearance beloved by Chinese—also breaks up wind force. "It's

like the opposite of an aircraft's wing," Mr. Katz explains. "It breaks up

lift."

Such innovation comes with every new skyscraper, which typically takes 10 years to build. Many liken the process to a space launch, since each new record-topping tower is, in effect, a brand new mission into the unknown. "Every time we build a new skyscraper, we learn new things," says Adrian Smith, architect of the Burj. He discovered vast temperature variations between the bottom and top of the building, data that could have been used to facilitate more natural cooling.

While many believed the era of supertall structures might have ended with 9/11, Mr. Katz says, "We're definitely getting into the next generation of supertall buildings."

Mr. Wood of the Council on Tall Buildings concurs. "Every day, we hear about new supertall buildings, in Brazil, Turkey or Vietnam."

The question, Mr. Wood says, isn't how tall they will go, but how well they will work in clusters. While the ICC offers wonderful linkage, this is only at the ground level. "What needs to come next is connections at higher levels," he says. That will be another big step toward the city of the future.

Ron Gluckman is an American reporter who has been based in Asia since 1991, roaming around the region, and beyond for various publications, including the Wall Street Journal, which ran this story in April 2011. Ron has written often about tall buildings, for such publications as Popular Science, Geo, Time, Silk Road and the Urban Land Institute.

All pictures by RON GLUCKMAN

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]