Lovin' Lisbon

After tracing Portuguese influences around Asia, Africa and Latin America for decades, a travel writer gets his first taste of the real thing - and is bowled over by Lisbon.

By Ron Gluckman / Lisbon, Portugal

A

SWEET, STRONG SEND OF NOSTALGIA washes over me the second I spy the familiar cobble stones and colonial buildings of the central square. Spinning around, I smile fondly while surveying the hills above, and see equally-familiar views of the old ruins of a castle overlooking the entire city, and the ancient church below. For a full decade of residence

in Hong Kong, such Old World sights were my reward,

and welcome respite from the frantic pace of one of the world’s busiest

cities. Simply imagining the intoxicating flavors and smells – delicious cod

dishes washed down by strong Portuguese wine – made my mouth water long before

every visit to Macau.

For a full decade of residence

in Hong Kong, such Old World sights were my reward,

and welcome respite from the frantic pace of one of the world’s busiest

cities. Simply imagining the intoxicating flavors and smells – delicious cod

dishes washed down by strong Portuguese wine – made my mouth water long before

every visit to Macau.

So it is no surprise that this holiday stirs those same juices. Yet the setting is a contrast. For this is not Macau, but rather the real root of those memories.

For the first time, I’ve landed in Lisbon. Experienced in the Luso-influences from Asia to Africa and Latin America, I’m still keen to finally check out the real thing. Roaming around Asia for nearly two decades, I’ve toured far-flung Portuguese outposts – Goa, Sri Lanka, Macau, even Faifo, or Hoi On in Vietnam – as well as numerous other places steeped in Portuguese influences, from Indonesia and Malaysia to Taiwan and Japan.

The May (2008) opening of perhaps Europe’s finest Asian museum – the Museu do Orient in Lisbon – provides the opportunity for a long overdue pilgrimage to Portugal. Having experienced only second-hand the influences on so much Asian architecture, cooking and ritual, I’m curious to see, at last, how the motherland measures up.

From first glance, Lisbon is an

alluring ménage of both old and new, and the latter is quite surprising. Since

Portugal was a pioneer in Asia five centuries ago, you expect churches and

historic stone structures on practically every corner of Lisbon’s lovely old

center. More startling is the gloss of a capital that has been nicely spruced

up, for its coming out party as European City of Culture in 1994, then the World

Expo in 1998.

From first glance, Lisbon is an

alluring ménage of both old and new, and the latter is quite surprising. Since

Portugal was a pioneer in Asia five centuries ago, you expect churches and

historic stone structures on practically every corner of Lisbon’s lovely old

center. More startling is the gloss of a capital that has been nicely spruced

up, for its coming out party as European City of Culture in 1994, then the World

Expo in 1998.

With all its pleasant pedestrian walks and art-filled plazas, new shopping malls and revitalized waterfront, Lisbon looks every bit deserving of its listing at the top of the recent New York Time’s Must-See destinations for 2008.

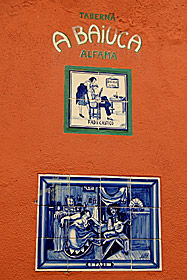

Sightseeing in Lisbon is a pleasure, with most tourist sites packed in the dense old town of Alfama, a charming Old World district of narrow, twisting alleys and endless cafes and churches, spilling out beneath the walls of the historic Castillo de San Jorge.

Just like in Macau, the ruins of the sprawling hilltop fortress make a perfect starting point for a walking tour. Unlike Macau, though, it’s a serious climb, as Lisbon is much bigger than its first outpost in the Far East.

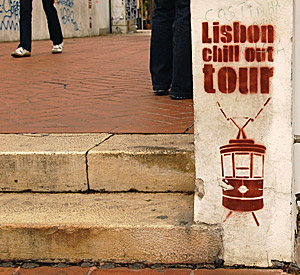

Fortunately, Lisbon has one of

the best transportation networks in the region, a huge and colorful matrix that

cannot help but recall Hong Kong, with buses, trams, a great subway system, plus

a trio of cute funicular trains that tackle the steep hills. The Passe Turistico

provides access to all with one convenient group pass (four or seven days),

while the Lisbon Card offers the same plus entry to most museums and other

sites.

Fortunately, Lisbon has one of

the best transportation networks in the region, a huge and colorful matrix that

cannot help but recall Hong Kong, with buses, trams, a great subway system, plus

a trio of cute funicular trains that tackle the steep hills. The Passe Turistico

provides access to all with one convenient group pass (four or seven days),

while the Lisbon Card offers the same plus entry to most museums and other

sites.

Not included – but definitely a once-in-a-lifetime treat – is the unique, century-old Elevador de Santa Justa. Quite an innovation in its time, with ancient cables and wheels, used to hoist citizens up the hill in olden days. Still running, it connects to an elevated walkway around the Archeological Museum that provides stunning views over the city. Picturesque in daylight, the views are absolutely breathtaking at night.

Even by modern bus, getting to the hilltop castle remains a challenge – there are just so many enticements along the way. Several times, we hop off at the sight of a steeple, to peak in another gorgeous church. Unlike typically overwrought old European churches, those in Lisbon seem subtle, or understated in style, often with spare ornamentation.

Outside, the churches are people

places, perched in nice plazas, with benches to savor seaside views. Lingering

is one of the main allures of Lisbon, but more on that later.

Outside, the churches are people

places, perched in nice plazas, with benches to savor seaside views. Lingering

is one of the main allures of Lisbon, but more on that later.

Reaching the castle, though, one is rewarded with a spectacular panorama, over a sea of tiled-roofs and white-washed houses that tumble down a hillside to the port. In the distance is the stunning orange bridge that naturally suggests the Golden Gate, from my pre-Hong Kong hometown of San Francisco. No surprise, as Lisbon’s bridge was built and designed by the same firm. Originally named Salazar Bridge, for the former dictator, it’s now called Ponte 25 de Abril, for the date of his ouster in 1974.

Heading back down the hill, we

make our way slowly to Praça do Comércio, the huge central

plaza in downtown Lisboa, like Macau’s beloved Senaco Square, only much

bigger, and more impressive. Also more atmospheric than anything in Macau,

with scores of locals meeting, greeting and gossiping at dozens of cafes. Tables

are placed anywhere there is space in the sun, and they are invariably full

morning to late.

This is the origin of Macau’s

four-hour lunches, always infuriating to always-in-a hurry Hong Kongers. But in

Lisbon, this lazy pace is not only ingrained, it proves infectious, especially

since the Portuguese are so friendly and inclusive. Time after time, we are

invited to tables, or treated to toasts by charming, chattering waiters.

At Pinoquio, a popular local

restaurant for over a quarter century (and toy store for the previous 70 years,

hence the name), Antonio pours us port and details all the highs, and lows, of

life in Lisbon. Mostly, it’s pretty positive, at least as I recall, but there

was a lot talk and toasts. Antonio bemoans how outsiders often mistake

Portugal for a province of Spain. It’s like how Macau slipped from the western

world’s gateway to China for centuries into Hong Kong’s shadow soon after

the British built their own colony.

At Pinoquio, a popular local

restaurant for over a quarter century (and toy store for the previous 70 years,

hence the name), Antonio pours us port and details all the highs, and lows, of

life in Lisbon. Mostly, it’s pretty positive, at least as I recall, but there

was a lot talk and toasts. Antonio bemoans how outsiders often mistake

Portugal for a province of Spain. It’s like how Macau slipped from the western

world’s gateway to China for centuries into Hong Kong’s shadow soon after

the British built their own colony.

Yet Portugal needn’t look to

Spain anymore than Macau might Hong Kong. Each place exists independently, but

also as a respite from the bigger, busier neighbor. I find the Portuguese far

friendlier, always eager to share everything – conversations, laughter and

especially meals.

Even more than in Macau, lunches

turn into dinners, and the days seem to dissolve into endless celebrations of

joyous consumption. Besides the food – rich as I remember from Macau, only

even more cholesterol-charged here, dishes literally swimming in olive oil –

and free-flowing wine, appropriate mention must be made of Fado, the mournful

folk opera that is to Portugal what flamingo is to Spain. If you somehow escape

all-day lunches in the old parts of Lisbon before dark, you’ll soon be swept

into clubs with open doors, and the haunting, irresistible Fado wafting out.

There is even a big museum in

Lisbon dedicated to this unique guitar-based ethnic music. But unlike in Macau,

where so much of the history and old traditions are sadly left to memory or

museums, in Lisbon it all remains alive and vital. The haunting Fado echoes

everywhere.

There is even a big museum in

Lisbon dedicated to this unique guitar-based ethnic music. But unlike in Macau,

where so much of the history and old traditions are sadly left to memory or

museums, in Lisbon it all remains alive and vital. The haunting Fado echoes

everywhere.

If such an upbeat picture of Lisbon seems surprising, perhaps that’s because most people in Macau, and Hong Kong, see Portugal as a declining or fallen power. This is partly due to its record in Asia – and everywhere from Africa to Latin America.

The early trading posts were long ago overrun by other European powers, and the

crumbs of the empire, places like Macau and Timor, suffered through downturns,

and worse, in modern times.

Likewise Lisbon and Portugal.

The poorest part of Europe

endured decades of economic gloom even after the overthrow of a repressive

dictatorship in the 1970s. Everyone points to the 1990s –

especially the Expo in 1998 – as the renaissance, with rebuilding on a

scale unlike anything seen since Lisbon recovered from its devastating 1755

earthquake.

Last year, Lisbon welcomed 2.84

million tourists, according to Vitor Carrico, the press and public relations

manager for Turismo de Lisboa. “That has been going up each year since 1998.

That was the turning point for Lisbon,” he says.

Last year, Lisbon welcomed 2.84

million tourists, according to Vitor Carrico, the press and public relations

manager for Turismo de Lisboa. “That has been going up each year since 1998.

That was the turning point for Lisbon,” he says.

Growth has been steady at around

10 percent annually, but equally important is an evolution in the quality of

visitors. Long known as a haunt for cheap European package tourists,

particularly the British who swarm the southern beaches, increasingly, Lisbon is

attracting a more sophisticated traveler.

“Lisbon has become a trendy

city in Europe, that’s the biggest change in recent years,” says Mariana

Rebelo de Sousa, director of public relations for the Four Seasons Ritz, one of

the oldest and most atmospheric hotels in town. Half a century old next year, it

remains a place famed for high tea. But now there are also power meetings in the

lobby.

“Lisbon has become trendy,”

she says. “It’s always had great weather, but now, there is better nightlife

and shopping. We get a lot more of your European jet-setters.”

Things should pick up even more

with the opening of the Museu Do

Oriente (Orient Museum) in the Portuguese capital May 9-11. In the planning for

nearly two decades, the 30 million Euro museum showcases a vast array of

statues, screens, snuff bottles, textiles, masks and other Asian art on five

floors in a magnificently restored neo-deco building along Lisbon’s waterfront

in Alcantara.

Things should pick up even more

with the opening of the Museu Do

Oriente (Orient Museum) in the Portuguese capital May 9-11. In the planning for

nearly two decades, the 30 million Euro museum showcases a vast array of

statues, screens, snuff bottles, textiles, masks and other Asian art on five

floors in a magnificently restored neo-deco building along Lisbon’s waterfront

in Alcantara.

Among the collections at what already is considered one of Europe’s prime Asian art museums are priceless pieces of Portuguese pottery, an intriguing array of crucifixes crafted in Asia for European export, and an unique ivory model of a Chinese pagoda, made in Macau in the 18th Century. The museum is also showing a selection of snuff bottles collected by Manuel Teixeira Gomes, Portuguese poet and, briefly, president, who assembled the second-largest snuff bottle collection in Europe.

By far the largest and most prized addition to the museum is the Kwok On Collection (sometimes called the Pimpanneau Collection), considered the world’s finest treasure trove of theatrical costumes and masks from Asia. Originally focused upon Chinese opera, the Kwok On Collection numbered thousands of pieces when it was exhibited at a Paris museum in the 1980s.

When that museum closed, the

collection passed to the Fundação Oriente, which has expanded it to over

12,000 items, newly catalogued and showcased in the temperature-controlled

vaults of the museum. There are also meeting rooms, a theater, restoration and

archive facilities at the exquisitely-restored Edificio Pedro Alvares Cabral,

which sat vacant for decades. Fittingly, with its dockside location, it formerly

did service as a warehouse for storing cod.

When that museum closed, the

collection passed to the Fundação Oriente, which has expanded it to over

12,000 items, newly catalogued and showcased in the temperature-controlled

vaults of the museum. There are also meeting rooms, a theater, restoration and

archive facilities at the exquisitely-restored Edificio Pedro Alvares Cabral,

which sat vacant for decades. Fittingly, with its dockside location, it formerly

did service as a warehouse for storing cod.

The museum is also a poignant reminder of Portugal’s role in opening Asia to western trade, and making Europe aware of the wonders of the East. And, in an interesting turn, the money for the museum actually comes from a former colony, Macau – and its gaming tables.

As part of a deal to extend his gaming licenses two decades ago, Dr Stanley Ho agreed to bankroll Fundação Oriente, which was set up in 1988. Over the years, the foundation has funded many projects in Asia, grants for study, and tours of Asian orchestras and cultural groups to the west. But the museum is by far the most ambitious and endearing project ever mounted by the foundation – opening on its 20th anniversary.

Ho noted that it should help

showcase Macau’s unique ability to act as link between China and Portugal. “I

believe that Macau, with its historical ties with Portugal and its unique blend

of Sino and Luso cultures, can well serve as a platform between China and

Portugal, in terms of trade, cultural exchanges and other forms of

co-operation.”

Oddly, as in the past, Portugal

seems unlikely to maximize the benefits of those links. Carrico,

at Turismo de Lisboa, concedes there are no promotion plans for Asia, and no

budget. Efforts are focused on Europe, which is closer and the source of most

visitors. Asia altogether, he says, probably doesn’t even total 10 percent of

Portuguese tourists.

Oddly, as in the past, Portugal

seems unlikely to maximize the benefits of those links. Carrico,

at Turismo de Lisboa, concedes there are no promotion plans for Asia, and no

budget. Efforts are focused on Europe, which is closer and the source of most

visitors. Asia altogether, he says, probably doesn’t even total 10 percent of

Portuguese tourists.

Possibly, the museum could help to change this, and boost the numbers. If so, visitors from Macau and across Asia would find much of historical interest, not only within the museum, but alive in the streets, plazas and cafes of Lisbon.

Ron Gluckman is an American journalist who roams around Asia - and beyond - for a wide variety of publications including Closer, which ran this piece in June 2008.

All pictures by RON GLUCKMAN.

To return to the opening page and index

push here

[right.htm]